Police could gauge which London neighbourhoods are most likely to suffer fatal stabbings by looking at non-fatal knife assault data from the previous year, a study suggests.

A Met Police detective manually trawled through crime data for 2016-17 and geo-coded 3,506 incidents where people were stabbed and cut but survived, using London’s 4,835 local census areas.

The data was then compared to the locations of the 97 London homicides in the 2017-18 financial year.

Research, published in the Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, indicates that the number of assaults resulting in knife injuries over one year correlates with an increased risk of deadly knife crime the next year.

“If assault data forecasts that a neighbourhood is more likely to experience knife homicide, police commanders might consider everything from closer monitoring of school exclusions to localised use of stop-and-search,” said study co-author Prof Lawrence Sherman from the University of Cambridge.

“Better data is needed to fight knife homicide.

“The current definition of knife crime is too broad to be useful, and lumps together knife-enabled injuries with knife threats or even arrests for carrying knives.”

Current crime statistics do not distinguish between incidents without injury – displaying of knives during robberies, for example – and those where knives have wounded.

“Police IT is in urgent need of refinement,” he said. “Instead of just keeping case records for legal uses, the systems should be designed to detect crime patterns for prioritising targets.

“We need to transform IT from electronic filing cabinets into a daily crime forecasting tool.”

Each assault analysed in the study was coded to a local census areas, some as small as a few football fields.

More than half of London – 2,781 areas – had no knife assaults at all in the first year.

Of these areas, 1% saw a homicide in year two.

Of the 41 neighbourhoods that had six or more injuries from knife assaults in the first year, 15% went on to suffer a homicide the following year.

The researchers argue that this reveals a large increase in homicide risk.

Detective Chief Inspector John Massey from the Met’s Homicide Command, who went through the data, said: “These findings indicate that officers can be deployed in a smaller number of areas in the knowledge that they will have the best chances there to prevent knife-enabled homicides.”

The study cautioned that using data to focus on assault hotspots is not a “panacea”, but Prof Sherman said it could “enhance the effectiveness of scarce resources” when combined with intelligence-gathering on the streets.

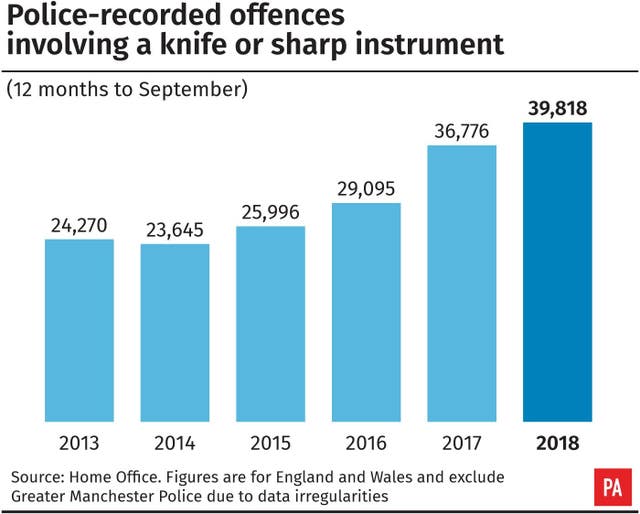

The study’s authors say the last decade of deadly knife crime has been a “moving target”.

The research found that in the 10 years up to 2018, there were 590 knife homicides across London spread over 523 different census areas – suggesting little repetition of homicide location.

The 41 top hotspots in the study contained only 6% of the following year’s total knife deaths.

No single area in the 2017-18 financial year had more than one fatal stabbing.

However, 69% of the knife homicides occurred in census areas where at least one non-fatal knife assault had taken place the year before.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article