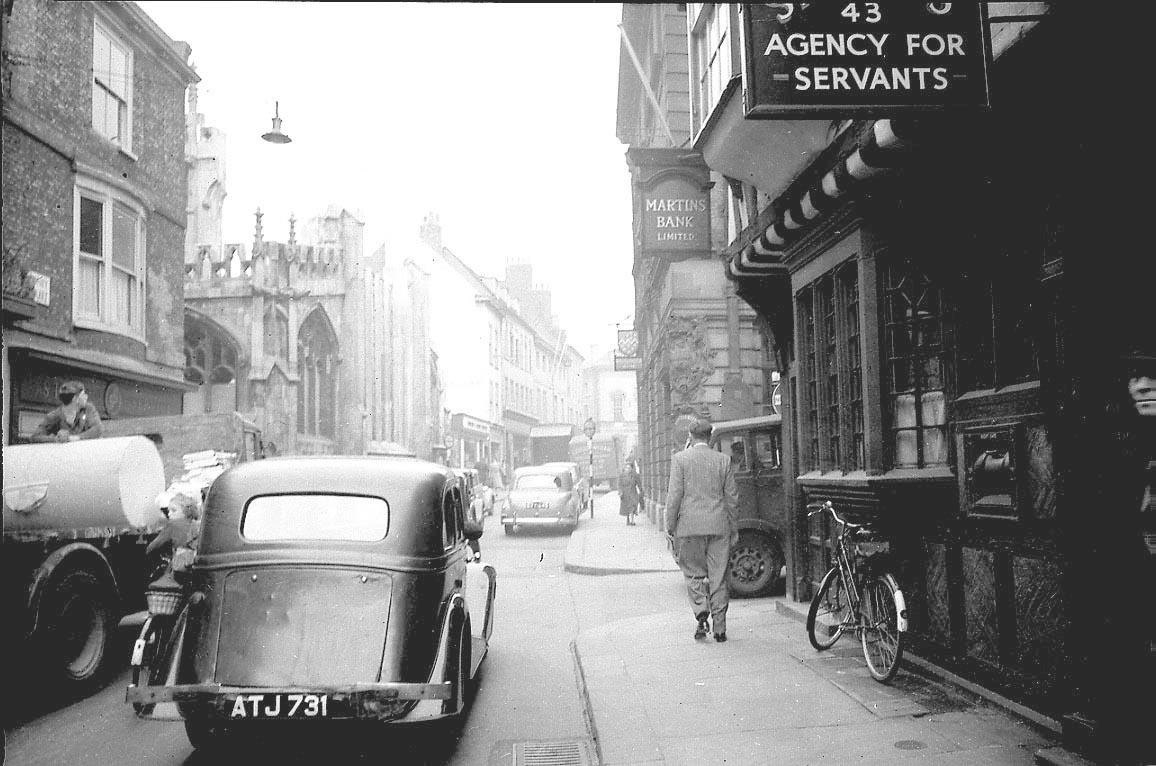

DAVID WILSON looks back at a time in York when we were even more socially unequal than we are today

AS I walked past the large Victorian terraced houses on The Mount and in Clifton, my eyes were drawn upwards to the small windows near or on the roof. For it is there that most live-in servants would have slept in this city in Victorian times.

My friend Kathy, who studied in York some years ago, told me that she’d lived in a small converted flat at the top of a large house in Telford Terrace, just off Albermarle Road near The Mount. "The bath was in the kitchen and the loo was on the next floor down," said Kathy.

Just after the turn of the century, in 1901, 1.5 million people, or four per cent of the total population across the United Kingdom worked as domestic servants. In the big houses of the upper classes, there was a carefully calibrated hierarchy of live-in domestic servants which may have included a house steward, a butler (and possibly under-butlers), valets, a housekeeper with various ranks of housemaids, cooks, gardeners, and stable boys. For the middle-classes, there were housemaids of various categories, depending on the wealth and social standing of the household.

In the 19th century, domestic service was the largest occupation open to women of the so-called lower orders or genteel poor, and servants continued to be widespread until the late 1920s, when challenging economic conditions and a greater variety of employment opportunities for women heralded a decline in servant culture.

It wasn’t really until after the Second World War that domestic service all but disappeared as a mainstream occupation.

In the Domestic Servants Wanted section of the Yorkshire Herald of April 25, 1891, there were many advertisements for the city of York. By March 1, 1933, the demand was much reduced. And by the 1950s, the language had changed. Most advertisers tended to ask for domestic help or mother’s help rather than maids or servants.

Life for live-in maids was difficult. They worked long hours. Servants were expected to work 14-16 hours a day with one half-day off a week and a Sunday half-day off once a fortnight.

Newspaper advertisements such as those in the Yorkshire Herald routinely specified the age and gender of the servant needed. A character reference was often required together with a stamped addressed envelope for reply.

In many middle-class York households, there would just have been one or two so-called maids-of-all-work. The duties of such maids, in particular, were extremely arduous. No training was given as a rule. They had to learn on the job. They had charge of the bed linen, and had to see to it that bedroom quilts, curtains and chair covers were kept in proper condition. They had to scrub the coal fire grates every day, carry in the coal, undertake polishing chores, as well as the sewing tasks of mending clothes, bedroom curtains and house linen.

We are talking, of course, about a time when the labour-saving devices we take for granted were simply not available. The introduction of the vacuum cleaner in the 1920s and the invention of later electrical domestic appliances certainly played a role in the demise of servant culture, but these were initially available only to the wealthiest households. It wasn’t really until the 1950s-1960s that vacuum cleaners, along with washing machines and fridges became more widely available.

The life of a live-in servant could be extremely lonely. They were isolated from the families of their birth, and employers did not generally agree to family members visiting them in their place of work. Amorous entanglements were disapproved of, and employers didn’t usually encourage household members to fraternise with the servants. In the days before sex discrimination and safeguarding legislation, servants were vulnerable to the sexual advances of unscrupulous employers and their young adult male offspring. In many cases, the servants, of course, would be summarily dismissed if they ever came to light. Not all employers were kind to their servants. Some employers routinely searched drawers in the maid’s quarters to check that they hadn’t stolen property from the household and there was the famous story of the employer placing a coin under a carpet in the drawing room to test the honesty of the parlourmaid.

When they got sick or old and unable to work, ‘old maids’ could be dismissed by their employers without any form of legal redress. There was no state pension scheme, but benevolent better-off employers would have allowed their servants to stay on in the household; the alternative was for the servant to return to their own family, or failing that, the last resort was the workhouse, where conditions were often dire.

I’ve painted here a highly negative picture of the servant culture of yesteryear. By modern standards the life of domestic servants was very hard. But in many cases, employers were kind and valued their servants while keeping a distant relationship with them. And for live-in servants, their quality of life was often incomparably better than it would have been outside. They were, after all, sometimes only one step away from penury and the workhouse.

Reflecting on the servant culture of yesteryear should give us pause to be grateful for the social advances in equality and anti-discrimination legislation that we enjoy today.

David Wilson is a community writer with The Press

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel