IN 1917 a young man from York began training as a student pilot officer with the fledgling Royal Naval Air Service.

The life of a naval pilot must, to 17-year-old Hugh Mortimer Petty, have seemed an inresistibly glamorous challenge. He'd be joining an elite flying unit attached to the British military's senior service. The RNAS had the pick of the best aircraft and the best training, and were attached to the best ships of the Royal Navy's formidable fleet.

The reality, of course, was tough and harsh and extraordinarily dangerous. Of the 23 young student fliers who passed out in Pilot Officer Petty's intake, just three - one of them the young York airman himself - were to survive the war.

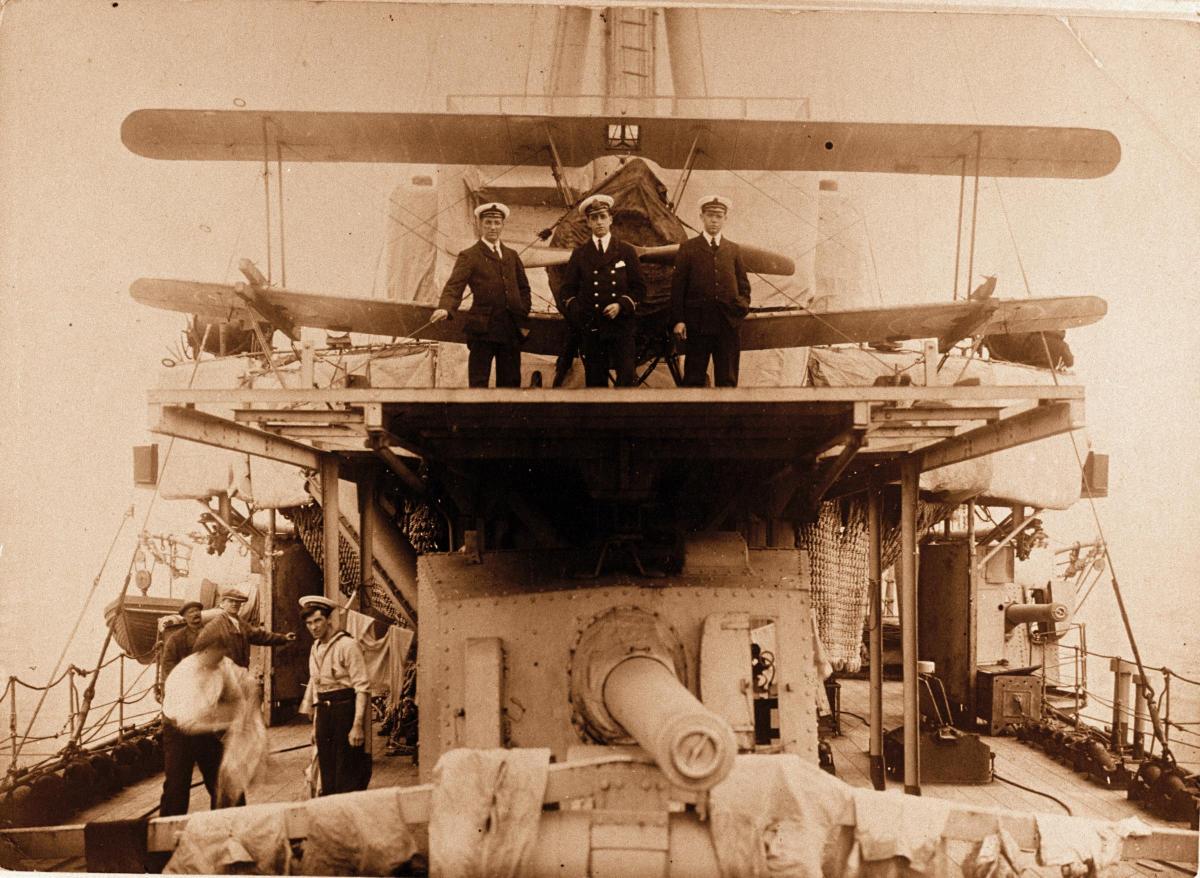

His main job as an RNAS pilot was to fly reconnaissance, providing intelligence about the movements of the German High Seas Fleet in the North Sea. He flew Sopwith Pup and Sopwith Camel biplanes, which were launched direct into the wind from the deck of battlecruisers. They were unable to return to land on their ships, so instead had to find a landing strip wherever they could - in Scotland often, or Denmark, or sometimes even in sea.

Student pilot officer Hugh Mortimer Petty, at the start of his training

Pilot Officer Petty crash-landed six times during his flying career - and on one occasion he even had to ditch his Sopwith in the icy waters of the North Sea, a few miles off the coast of North Berwick.

That was an extraordinarily dangerous practice, admits his son, Dr Richard Petty, a London-based private physician.

"The aircraft's wheels were not retractable, so they caught in the sea and the aircraft flipped over. Often the pilot would knock himself out on the side of the cockpit, then drown." The observer was often more fortunate - he'd often be flung clear and could hope to be rescued.

In the event, both Pilot Officer Petty and his observer survived, to be rescued by the crew of a British destroyer.

The rescue: a boat carrying Pilot Officer Petty after his Sopwith was ditched into the North Sea

The young airman only flew with the RNAS for 18 months before the armistice was declared in 1918 - but he packed into those few short months a lifetime's worth of adventure.

What makes his wartime story all the more extraordinary is that we have an astonishing photographic record of it.

From September 1917 to December 1918, strictly against all regulations, he carried with him a Kodak vest pocket camera. He slipped this into his pocket - and throughout his training and active service, he and his colleagues managed to capture a series of extraordinary images.

They run from his early training days at Eastchurch and Cranwell, through gunnery and deck training in the Firth of Forth to patrols, convoys and even that unexpected ditching in the North Sea. And Pilot Officer Petty is also thought to be the only man who recorded on camera the Armistice and surrender of the German Fleet at Scapa Flow.

Battlecruiser HMS Inflexible

Many in the British Grand Fleet thought it may be a ruse by the German High Fleet to lure the Royal Navy into a trap, Dr Petty says, so there was a good deal of tension. Pilot Officer Petty was in his cabin aboard a battle cruiser. "But he opened his porthole, stood on his sea-chest, and took photographs," Dr Petty says.

After the war, the still-young Hugh Petty continued with the medical education that had been interrupted when he signed up for pilot training.

A German light cruiser at the surrender of the Hugh Seas Fleet, November 1918

The son of a prominent York Methodist family - his older half brother Richard pPetty was a York lawyer who was gassed during the war; his older half sister Dorothy was a teacher - he had gone to Elmfield College in York, before going to Leeds at the age of 17 to begin studying medicine.

On leaving the RNAS, he resumed his medical studies, and eventually went on to become an ear nose and throat surgeon, in Leeds and the West Riding.

Richard, his son, was born in Doncaster, and himself went on to become a doctor.

When his father died at the age of 77 in the 1970s, Dr Petty discovered the negatives of the extraordinary photographs in his father's sea trunk.

On the deck of HMS Marlborough during Sunday Parade at Scapa Flow

He carefully preserved them, and last year many were published in a book The Boy Airman, An Absolute Stranger to Fear, that Dr Petty wrote in memory of his father.

Now the people of York can see many of them for themselves, at a new exhibition that has just opened at The Castle Museum.

Dr Petty has had high quality reproductions made of many of the photographs, and they feature - alongside his father's camera, compass, fuel gauge and flask - in the Community Room at the museum as part of its ongoing 1914: When The World Changed Forever exhibition.

It makes for a truly revealing exhibition about a comparatively little-known aspect of the First World War.

“Much of the charm of this exhibition lies with Hugh’s story," says Dr Faye Prior, collections facilitator at York Museums Trust. "But the fact that we have been given the chance to see a view of the First World War that we wouldn’t otherwise get is fascinating.

“There are some lovely candid photos that are a great insight into Hugh’s experiences of the First World War and the images of aircraft and ships will really appeal to enthusiasts.”

The exhibition runs until the end of February. It is one not to be missed.

A 'pile of pilots' during early training

Exhibition details

The Boy Airman, an exhibition of photographs taken by Hugh Petty and his colleagues during the First World War, is on display in the Community Room at theYork Castle Museum until February 29.

Dr Richard Petty's book The Boy Airman, An Absolute Stranger To Fear is published by Pen & Sword, priced £19.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel