ON a day some time around 1400 BC, a wealthy Egyptian named Sennefer sat down to write a slightly grumpy note to one of his tenant farmers.

Sennefer was the Mayor of Thebes, and a childhood friend of the pharoah Amenhotep II. His note was to warn his tenant, Baki, that the pharoah was coming to visit, and that Baki should get Sennefer's rural estate in order.

"Don't let me find fault!" he warned. "Pick me many plants, lotus blossoms and other flowers to be made into bouquets fit for presentation. And don't be lazy! For I know you are lazy and like eating in bed!"

Joann Fletcher can't help giggling when she recites this 3,400-year-old note from a rich man to his lackey.

"It's just so human!" she says. "You can imagine this Egyptian farmer, bone idle, sitting there in bed having his dinner..."

Classic image of Egypt: the pyramids

Most of us, when we think of the ancient Egyptians, think of the pyramids, or those strange sideways-on wall paintings of people in elaborate head-dresses - or the death mask of Tutankhamen.

Such objects make the people who built this most ancient of civilisations seem remote, utterly strange - even a little alien.

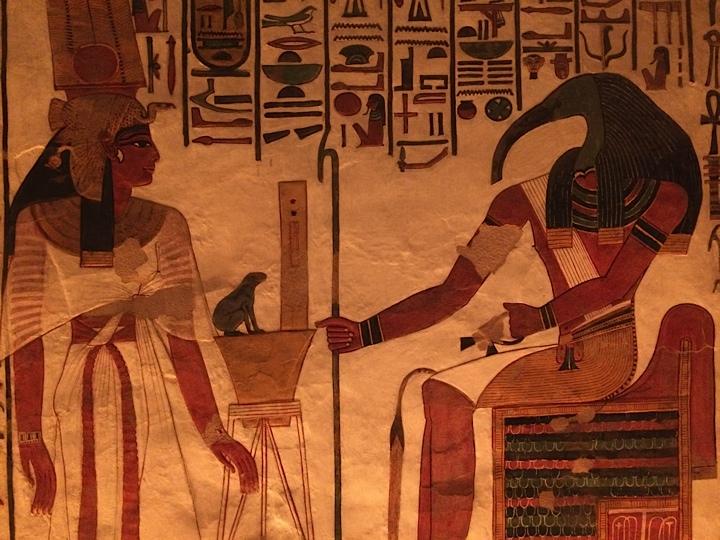

Alien: The ibis-headed literacy god Thoth in a wall painting from the tomb of Queen Nefertari in the Valley of Kings

Yet what Prof Fletcher loves about the Egyptians was just how much like us they actually were.

We know that from the letters, notes and even love-poetry that have survived for thousands of years.

They weren't all written by official scribes or wealthy men like Sennefer. The tiny village of Deir el-Medina was home to generations of stoneworkers and artisans who built the tombs of the pharoahs in the Valley of Kings. Astonishingly, Prof Fletcher says, as many as 40 per cent of the people of this village were literate. And they left behind them, preserved in the dry desert heat, hundreds of letters - and thousands of postcard-like notes, that were, Prof Fletcher says, the equivalent of today's text messages.

In one, a man named Paser wrote to his wife Tutuia: "You sent me a message and I came" (good advice that for any husband who wants a quiet life). Then there was a young woman called Isis, who wrote to her sister Nebuemnu: "Please weave me the shawl, very, very quickly. And make one for my backside." That last, Prof Fletcher believes, was probably a reference to a sanitary towel.

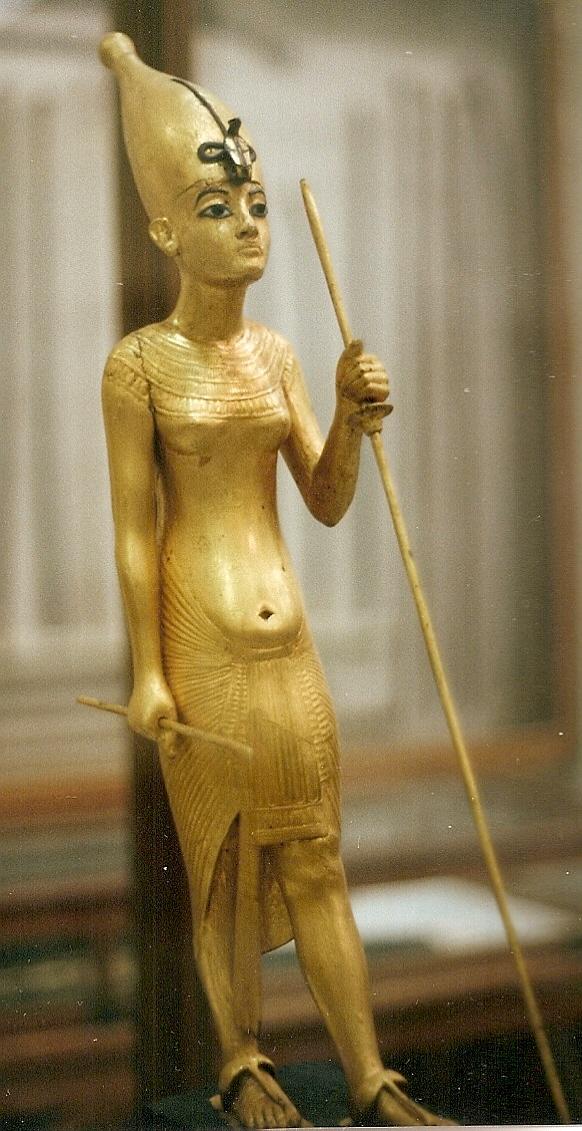

Gilded statuette of Queen Nefertiti

The Deir el-Medina collection includes everything from self-help manuals to medical texts and even ghost stories - the Egyptians loves their ghost stories, Prof Fletcher says. And there is even love poetry, such as this, ascribed to a woman known as Tashery: "You restore her in the night when she says to you 'take me in your arms and let us lie like this til dawn'."

Prof Fletcher, who is based in the University of York's Department of Archaeology at King's Manor, includes a selection of these ancient letters, messages and poems in her new book The Story of Egypt.

It is a book that is steeped with her own love of Egypt. In less than 400 pages it takes in the full, grand sweep of Egyptian history, from the first 'pre-dynastic' settlements along the banks of the Nile in about 4000 BC right up the the time of Cleopatra four thousand years later.

You'll find out about 'Ginger', Egypt's earliest-known murder victim - named for the red colour of his hair - who died after being stabbed in the back 5,500 years ago; Hatshepsut, the female pharoah who, 3000 years before Elizabeth II, ruled as an outright monarch in her own right; and Amenhotep III, Prof Fletcher's favourite pharoah, who ruled from 1390 to 1352 BC in what was a golden age for Egypt. He had more than 300 wives, but wasn't above writing to foreign kings demanding they send him more, specifying only that they shouldn't have 'shrill voices', Prof Fletcher says.

She herself has been in love with Egypt ever since, as a six-year-old girl growing up in Barnsley, she first saw the Tutankhamen exhibition, complete with that extraordinary golden death mask.

From that day on, she knew she wanted to devote her life to studying the Egyptians, she says: so much so that her parents used it as a way to encourage her to study well at school. "My mum said 'if you work really hard at school, you can be an Egyptologist.'"

The Egyptologist: Joann Fletcher in Egypt

When she was 15, in 1981, she got to visit the country with her aunt, and did all the usual touristy things: visiting Cairo, Luxor, the pyramids, the Aswan Dam. The last day she spent in the Cairo museum with the antiquities.

The holiday sealed her infatuation with all thing Egypt.

"It was really stunning," she says. "The colours, the people, everything."

She went on to study Egyptology and ancient history at University College, London, then did a Ph.D at Manchester. Today, the little girl who once marvelled at Tutankhamen's death mask has become one of our foremost Egyptologists: the author of nine books and numerous articles and a TV regular who has written and presented programmes such as 'Life and Death in the Valley of the Kings' and 'Egypt's lost Queens' for BBC 2.

Her passion for Egypt remains undiminished - as anyone who reads her new book will spot straight off.

She regularly spends weeks at a time in the country, she says - and has even been 'adopted' by an Egyptian family who live on Luxor's west bank, conveniently handy for the Valley of Kings and Deir el-Medina.

One thing she loves about being in modern Egypt is the way you can see the ancient past reflected in ordinary, everyday things around you.

The Egyptians still eat big round loaves of bread almost identical to those that were a staple thousands of years ago, she says. "And there are still some houses built of mud bricks in a style that was standard throughout pharaonic times."

Religions, cultures, even civilisations come and go. But some things never change. The Story of Egypt is a reminder of that.

- The Story of Egypt by Joann Fletcher is published by Hodder & Stoughton, priced £25.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel