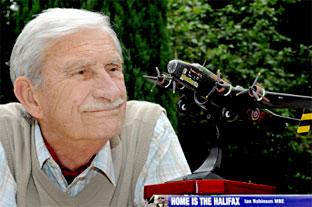

Once the skies above North Yorkshire were full of Halifax bombers, now only one remains. MATT CLARK meets the man who led its restoration.

WHEN Ian Robinson made model planes as a boy, it never occurred to him that one day he might build a real one. But in 1996 he stood proudly with his team as members of the public joined veteran aircrew to gaze at the only complete Halifax bomber in the country.

For Ian it was the final piece in his jigsaw, the crowning glory of the Yorkshire Air Museum, to which he devoted 13 years of his life.

Now he has written the story of how the aircraft came to be there and his passionate desire to see it housed in a permanent memorial to airmen who lost their lives on wartime missions from bases near York.

In Home Is The Halifax, Ian takes us back to 1983 and a conversation with Rachel Semlyen, who lived near the disused airfield at Elvington. Rachel used to walk her dog there and was struck by the atmosphere of the place; she told Ian it would be a perfect site to honour the Second World War heroes.

“There was this huge air armada between 1940 and 1945, like a land-based aircraft carrier, and most of the airfields operated Halifaxes,” says Ian.

“So many thousands of aircrew were lost, but apart from the Book of Remembrance in York Minster, very little was known locally about all the efforts of these many, many squadrons of the Royal Air Force.

“Then Rachel and another friend of hers called Ian Wormald got the idea of trying to create some form of memorial in these little run-down buildings at Elvington. It was going to be a memorial museum and that really set me going.”

In time, a group of aviation enthusiasts got together, Ian agreed to be in charge, and the Yorkshire Air Museum began to take off.

Elvington had been a French base during the war and the first lucky find was some rare footage of the air traffic control tower, which allowed Ian and his team to recreate the building exactly as it was. Other work included restoring the NAAFI and chapel, as well as building a hangar, but Ian always knew the museum should have a Halifax bomber as its centrepiece.

The trouble is none had survived.

“A commemorative museum to the Allied Air Forces without a Halifax would be like a frame without a picture,” he says. So began years of painstaking work by a dedicated team of volunteers who decided to build their own with as many original parts as possible.

Ian found the first piece by chance when he heard of a derelict section of Halifax fuselage which was being used as a hen coop by a farmer on the Isle of Lewis. He had bought it after the war, when aircraft based at Stornoway had been scrapped, and by the eighties it had half-sunk into a peat bog.

So Ian organised a JCB, asked the RAF to come to the rescue – which they did by sending a helicopter – and drivers from his firm volunteered to collect the piece of airframe. Then came the huge task of gathering the hundreds, if not thousands, of bits they would need to faithfully reproduce a facsimile of the bomber. And the project needed lots of willing helpers.

“People just came out of the woodwork,” says Ian. “It was amazing; we had everyone from doctors to architects and civil engineers. All were skilled men and it was marvellous.”

More help arrived when British Aerospace apprentices manufactured the fuselage as part of their training course. And once word got out, Ian’s phone kept ringing as people who had dug up pieces of crashed Halifaxes in France and Germany, offered to send them to Yorkshire.

The team already had a stroke of luck when the original plans turned up. Handley Page had gone bust many years before and most of its documents were incinerated. But one employee saved the Halifax drafts and sent them to the Imperial War Museum in Duxford. He told Ian when he heard about the Elvington project.

The aircraft took 12 years to build, mostly from scratch, and appropriately enough the bomber – christened Friday The 13th – was rolled out on Friday 13, 1996. It was named after the most illustrious Halifax to have flown with Bomber Command, which flew 128 successful missions with 158 Squadron, from Lissett, East Yorkshire. After the war it suffered the ignominy of being dismantled for scrap.

“Because of all the volunteers, the Halifax actually cost very little to make and the day it rolled out was really thrilling,” says Ian.

“The queue of cars went all the way to Grimston Bar and down the A64. There were VIPs, people who came from all over, and of course there were the veterans. Many of them were in tears as they got the chance, once again, to sit in the cockpit of a Halifax bomber. Since then, I think it’s given a lot of pleasure to many people.”

With help from his wife, Mary, Ian has written about the 16 happy years they spent at Elvington, which earned him an MBE. His book records how much effort went into creating the museum and building the Halifax.

“The whole thing gathered momentum from the start,” he says. “It was great fun and I’ve included some of the stories that came out of my time at the Yorkshire Air Museum.”

Tales such as the one about a Whitley from Linton-on-Ouse that was dropping leaflets over Germany at the start of the war. The crew got lost as they were heading for a base for France, so when they spotted a field, they landed.

When the navigator got out, he saw a cyclist and ran across to him. He asked, “Could you tell us where we are please?” The cyclist replied that they were still in Germany and France was, “Just over there”. So the navigator got back in the plane and they took off again. The unfortunate German ended up in jail for aiding the enemy.

The story, told in a letter sent by the pilot to his brother, is still on display at the museum.

Ian has loved aircraft all his life and during the war he was given the chance to fly while working as an engineer at Clifton Moor. The base was a repair depot for Halifaxes and at the age of 17 he was selected to be a flight engineer for Handley Page’s company test pilots. But as a civilian he never went on operations.

“I felt a little bit guilty about it at the time and a lot guilty ever since. I knew so many men who went on missions and who never returned, because we often went to the bases if they had an aircraft that they couldn’t rectify, and I used to go into York to places like Bettys. So I got to know a lot of aircrew – and sometimes they disappeared.”

Ian’s motive for the memorial museum was to pay his dues to those brave young airmen and to let others understand the conditions people worked under and flew in during the war. One of the key things for him was to get school parties along, so a building was set up for educational use.

“I got the impression that children were overawed when they heard veterans telling stories of flying big bombers like the one they had seen in the hangar.

“I think at the museum we achieved what we tried to achieve which pleases me, because the men of Bomber Command didn’t get any recognition after the war and it was shocking that they didn’t get a medal. I think the lads got a bad deal but it’s good to see that a memorial is finally going to be built in London and any money I make out of the book will go to that.”

• Home Is The Halifax is published by Grub Street and costs £20. Ian Robinson will launch the book at Sherburn airfield on August 12 and it can be pre-ordered through Amazon.

BETWEEN 1935 and 1945, Yorkshire was home to 41 military airfields, the majority located in the Vale of York. Some 30 operational squadrons operated from the bases and a Book of Remembrance in York Minster records more than 18,000 airmen who died on active duty in Yorkshire.

The Handley Page Halifax was a heavy bomber with a crew of six to eight. It had a maximum speed of 280mph (312mph for the MarkVI), could fly at 22,800 feet and had a maximum range of 3,000 miles. The one at the Yorkshire Air Museum is a Mark III.

The Halifax first saw RAF service in 1941 and was used extensively in Europe and the Middle East with variants used by Coastal Command, 6177 examples were built, but not one was saved for posterity. The only other restored example is in Canada.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel