All week, we are bringing you eyewitness accounts of the York Blitz. Today, we hear about the dreadful damage to Coney Street, and a tale of survival from Blake Street.

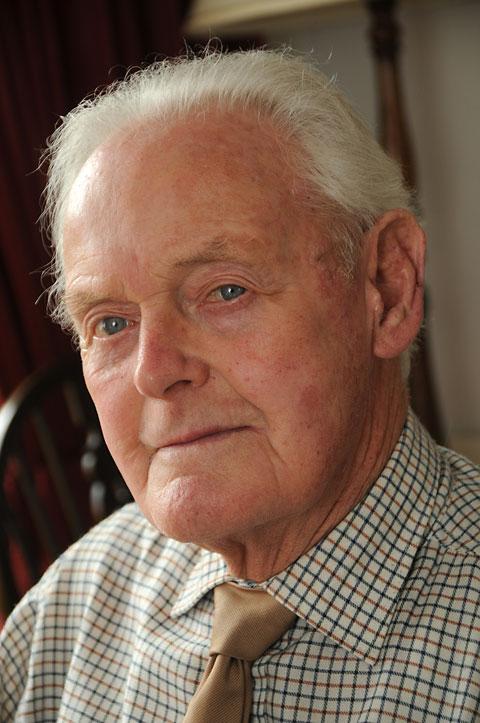

James Sydney Bell

The night of the York Blitz was 17-year-old James Sydney Bell’s very first on duty as a volunteer fire warden.

The young James worked as an apprentice butcher at the York Co-operative society in North Street. Keen to do his bit in the fight against Hitler, he had volunteered to stand fire watch on the building’s roof. That night of April 28/29, 1942, was his first on duty.

“It was quite eye-opening!” recalls Mr Bell, now 77 and living in Howe Hill Road.

It was a beautiful, clear night, with a full moon. From his position on the roof of the Co-op, the young James could see across the river to the Guildhall.

He was sitting enjoying a cup of tea when the sirens went off. There was the shattering roar of low-flying aircraft, and then the flash of incendiary bombs.

They rained down, all around North Street, the station, the Guildhall and Coney Street.

Somebody shouted: “Get downstairs! They’re dropping bombs!” James lost no time complying. It was pretty terrifying, he admits. He remembers at one point running to take shelter from the falling bombs under a set of wooden steps. Then he and his volunteer colleagues took their buckets and started trying to douse the fires that were taking hold all over. They ended up on Lendal Bridge, trying to put out two fires there.

Then James was asked to carry a message across the river to Coney Street. He jumped on his bike and cycled across Lendal Bridge. The sight that met his eyes when he turned into Coney Street will never leave him.

“The church (St Martin-le-Grand) was well afire, and so was the Guildhall,” he says. “I remember seeing flames coming out of the church windows, and the beautiful stained glass bursting and falling into the middle of the road,” he says.

The tarmac of the road’s surface had melted from the heat. “And the following day bits of stained glass was found embedded in the road.”

James wasn’t allowed down the street. “They said ‘go back where you came from, son!’”

Back in North Street, a fire brigade pump had arrived, and the battle was on to stop the flames spreading more widely. “We were trying to stop the flames spreading to the old church (All Saints’) in North Street,” Mr Bell recalls. Thankfully, the church and its priceless stained glass – including the medieval Pricke of Conscience window that depicts the end of the world – still stand today.

Eventually, once the bombs stopped falling and the worst of the fires had been brought under control, James was told to go back home.

“They said ‘get yourself home, lad! Your mother and father will be worrying about you’,” Mr Bell recalls. The family lived in Acomb. He jumped on his bike, and cycled up Micklegate, which was undamaged. When he got past Micklegate Bar, however, he was shocked to see the Bar Convent had been hit. “The rubble was halfway across the street.” He continued pedalling home – and halfway there came across his father pedalling in the other direction to find him.

His father, a railwayman, had been on a train that had been heading to York Station and had had to stop at Hob Moor because the station was ablaze.

He had rushed home only to learn his son was out tackling the flames in the city centre. “My mother told him to ‘go and see where our lad is’, Mr Bell says.

Hazel Laws/Rhoda Walker

HAZEL Laws remembers absolutely nothing about the night of the Blitz – even though she was right in the thick of it.

At the time of the air raid, she lived with her family at No 3 Blake Street.

Its front door was blown in by one of the German bombs and she only survived by sheltering with her mother, sister and two brothers in the cellar.

You’d think something like that would stick in the memory. But then, Hazel was only six months old at the time.

Hazel, now a grandmother aged 70 who lives in Rosedale Avenue, knows all about her early brush with death, however – thanks to her mother’s vivid account.

Her mum was Rhoda Walker, who died in 2003, aged 94.

On the day before war broke out, Rhoda had taken up the post of caretaker at what is now number 18 Blake Street.

Together with her children and second husband, Sydney, who worked on the railways, they moved into the top floor of the townhouse.

The building was home to the long-established law firm of Munby & Scott.

Many years later, Giles Scott, a partner in the firm – which merged with Langleys a few years ago – asked if Mrs Walker would write down some of her wartime experiences. She did just that…

Rhoda Walker’s memories of war

“Many nights were spent in the cellar awaiting the all-clear. With three children, this was an ordeal, we had sleeping facilities and games etc.

“The main blitz on York came. After an early warning we managed to escape once again to the cellar, this time taking two female wardens from Anfield’s Milliners shop with us – they were too afraid to do fire watch on the roof.

“It was a night of terror, one warden kept fainting with fear – terrific bombs exploded and later we were told of fire bombs all around us.

“My husband was on night duty at the railway. He came off duty at 6am to be greeted with police and wardens saying we weren’t expected to be alive, a large bomb having fallen next door.

“However, wardens entered the cellar from a man-hole in the pavement to find us all alive but petrified!”

The large bomb had fallen on the greengrocers nearby and demolished the three-storey building, together with St Martin’s Church and the Leopard shopping arcade in Coney Street.

“Not a window was left, nor a door still hanging.

“Blake Street was ankle deep in glass and the large Victorian door at No 3 was blown along the passageway to the back. Upstairs in the offices and our flat, the windows, doors and furniture everywhere were badly damaged.

“There was not a pane left anywhere and beds were covered with glass. In addition, firebombs had fallen all around.

“We left to spend weeks at Warren Farm, Dunnington, where my in-laws lived. Two of our children were listed on the casualty list at school, but I soon rectified that.

“I came back to Blake Street and along with Felicity Scott helped to clean up the buckets of soot and glass.

“One office was made habitable - our flat took weeks to rectify and in all it took two years to complete.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here