Has the last Yorkist king finally been discovered? Archaeologists seem to think so and if they are right where should Richard III’s final resting place be? MATT CLARK reports

IT PROMISES to be a winter of discontent with academics fighting one another over a most contentious question: have the remains of Richard III finally been found?

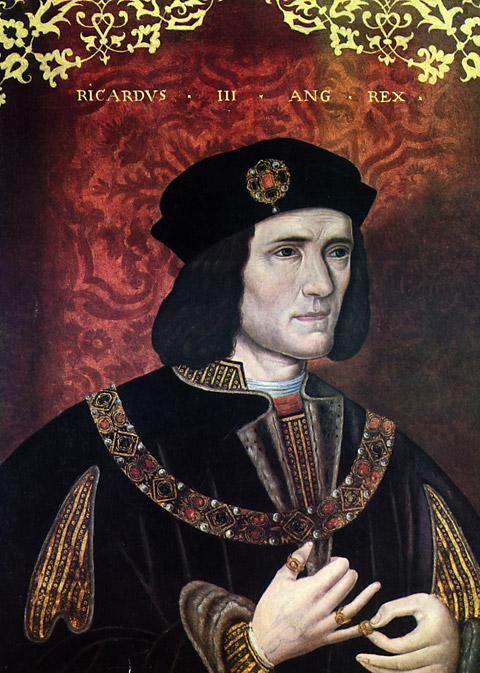

Richard was the last Yorkist king and one with radical ambitions. He planned to move the royal court to York and in 1483 announced his intention to build an enormous chantry chapel at the Minster, where he would be buried with 100 chaplains praying for his soul.

But for all his grand plans, Richard’s wish list never happened. He was killed two years later at the Battle of Bosworth and rather than resting in peace under the magnificence of York Minster, his body may just have been discovered lying beneath a car park in Leicester.

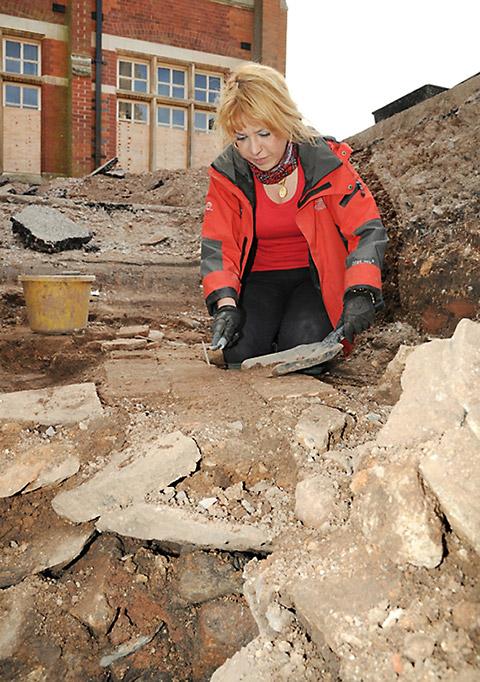

This stands on the site of what was the Franciscan friary of Greyfriars until the 1530s. As the defeated foe, Richard was given a low-key burial in the friary and documents describing the burial site have survived. Now the choir area has been excavated and at the spot where Richard was interred, archaeologists have discovered a skeleton.

One of Richard’s descendents has now been traced and DNA tests are about to be carried out on the skeleton to prove whether or not it really is the Plantagenet monarch.

If it does to prove to be Richard once the results are back, the next great debate will be: where should his remains be sent?

Twitterers have already started the discussion with some suggesting the body should be given a State funeral. Then there is the international Richard III Foundation which has announced its campaign for the burial place to be York Minster.

All are jumping the gun perhaps, but experts at the University of Leicester seem pretty sure of who they have found. Evidence included signs of a peri-mortem trauma to the skull and a barbed iron arrow head in the area of the spine.

Richard is said to have been pulled from his horse and killed with a blow to the head.

The skeleton also showed severe scoliosis – a curvature of the spine.

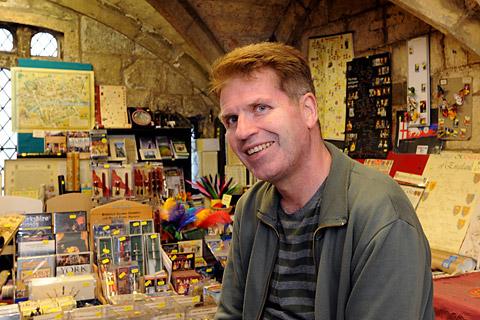

Michael Bennett, who runs the King Richard III Museum in York, believes if it is Richard, he should be brought back home.

“I think the north is a better place for him to be buried because he was Lord of the North,” says Michael. “They can’t bury him in York Minster because they don’t bury people in cathedrals any more, but I think he should be interred in the Minster grounds.”

Another debate running on the back of the discovery is who was the real Richard? History tells us he was one of England’s most infamous monarchs and the traditional impression is of an evil hunch-back. But what was Shakespeare’s motive in making Richard so grotesquely contorted? “The enduring image of Richard III is Olivier’s famous overacted monster with the false nose,” says Michael. “But evidence suggests he wasn’t hunch-backed, he just had the same curvature of the spine that Usain Bolt has.”

And it’s not just an unflattering portrait. Richard is associated with murder and skulduggery, especially slaying his nephews in the Tower of London. But had he really been plotting for the throne his entire life?

“I think it was all a huge mass of Tudor propaganda, accentuated and increased by Shakespeare’s play,” says Michael. “Richard was of his time and they were brutal years, but he seems to have been a kindly, benevolent and pious man; completely opposite to the impression the Tudors wanted to give.”

Indeed Richard’s motto was Loyaulte me Lie (Loyalty binds me) and he earned a reputation for fair-mindedness and justice.

“Richard only had two years and in that time he introduced bail, juries and abolished a few taxes, notably benevolence tax which gave the king a chance to raise money for pointless battles.

“Something like that is good to have on your CV if you’re a monarch.”

Certainly Richard was hugely popular in York. He had a strong affinity with the city and courted the goodwill of the council and the Minster clergy. York also looked to their king for help at a time of economic decline, and actively championed his short reign. The city sent troops to support his cause, including 80 dispatched to support him at Bosworth Field. But they arrived too late and the Tudor era had begun.

York mourned and the day after Richard’s death on August 22, 1485 the mayor’s serjeant of the mace wrote, “King Richard, late mercifully reigning over us, was through great treason… piteously slain and murdered, to the great heaviness of this city.”

It’s no surprise York is rich in his memorabilia. Apart from the King Richard III Museum, the Yorkshire Museum has several important finds. The Middleham Jewel is perhaps the most famous, but there is also an exquisite gilt spur found at Middleham Castle.

Could it have belonged to Richard? A very wealthy nobleman certainly owned it and Richard spent a lot of his life at the castle, so there must be a chance.

Natalie McCaul, assistant curator of archaeology at the museum, says Richard was a much-loved king, especially in York, and agrees with the Tudor propaganda theory.

“For a new ruler like Henry, the best way to make people like you is to make them doubt the person before,” she says.

“Richard makes a brilliant baddie for Shakespeare, but the chances are none of it is true. It’s a yarn meant to put him in a certain light and I don’t think he is anywhere near as black as he is painted.”

More evidence of Richard’s popularity is on display at the Yorkshire Museum, in the shape of a rare 15th century badge worn to show loyalty to the Yorkist King.

Made of silver gilt and in the form of a boar, a symbol of the King, it was found by a metal detectorist near Stillingfleet and the museum has recently raised enough money to both buy and restore the item.

Because it is silver-gilt the badge would have belonged to someone of high status. Natalie says it is an exciting and rare find and because of its connection to Richard III, very important to Yorkshire.

The final decision over Richard’s remains would lie with the royal family. York Minster must have the strongest case; it is after all where Richard intended to be buried, but Leicester already has a memorial in its cathedral given by the Richard III Society in 1984 and he has been buried in the city for half a millennium.

Yorkshire has another claim at Middleham Castle, where Richard and his wife Anne Neville made their first and favourite home. It was where the couple’s only son, Edward, was born in 1473, and where he spent most of his tragically short life.

Yorkshire has an infallible case until you look at the traditional War of the Roses view which says York was in conflict with Lancaster in a divide that split the country into civil war.

But many academics believe that the House of York was a southern-based administration and much of Yorkshire was ruled by the opposing House of Lancaster.

That gave a north/south division rather than east/west, as was previously thought.

That said, Richard was adamantly against life in London and preferred Middleham Castle and York, presumably that is why he asked to be buried at the Minster.

“Of course he should come to York it’s where he wanted to be buried, he belongs here and we would welcome our king like we did 500 years ago,” says Mike.

“However, I tend to think he will end up in Leicester, after all they funded the dig.”

• The King Richard III Museum is at Monk Bar York. There are three rooms in all, the uppermost is said to have been added by King Richard himself in 1484, allegedly supervising its construction and paying for it out of his own money. The museum is open daily from 9am- 5pm seven days a week and the top floor has just been renovated.

Why the body was taken to Leicester...

AFTER the battle of Bosworth Richard’s body was taken to Leicester and displayed so people could see he was dead.

Greyfriars was considered a convenient and safe place to bury the former King without generating a posthumous cult and there is evidence that people talked about him being buried there.

In medieval England people who were political victims were believed to become popular saints. Richard becoming one would have been unthinkable to the Tudors and it ruled out his wish to be buried at York Minster where he was much loved.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel