Life wasn’t good in York 100 years ago if you had a German-sounding name. STEPHEN LEWIS reports on the launch of a new walking trail which reveals some surprising facts about life in the city during the First World War

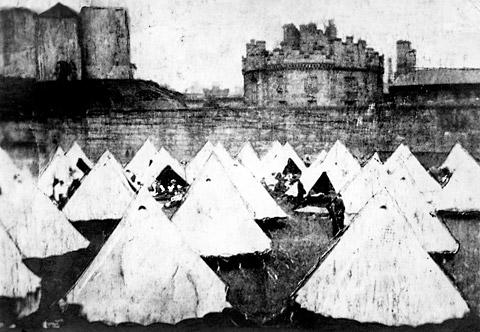

Ninety-eight years ago, as York struggled to get to grips with the fact that the nation was at war with Germany, a tented city sprang up in the shadow of Clifford’s Tower.

It was a temporary detention centre for German-born civilians, who had been arrested when the First World War broke out.

The city, like much of the rest of the country, was in the grip of a wave of paranoid ‘spy fever’. Anyone with a German-sounding name was at risk: and families were torn apart.

‘Enemy aliens’ with German-sounding names from all over the county were brought to the encampment. They included Edward Schumacher, a 62-year-old engineer with a workshop in Coffee Yard, who had been arrested while boarding a tram to Acomb .

“He was detained at the prison as a potential security threat, despite having an English wife and a son, George, serving in the Royal Field Artillery,” says Helen Weinstein, Professor of Public History at the University of York , and director of the university’s Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past.

He was by no means the only local man to come under suspicion. Another of those impounded at the prison was Julius Koch, the manager of the Olympia Oil Mills in Selby . Several of his employees were also detained for good measure.

Others fell foul of the Aliens Restriction Act which had been passed on August 5, 1914 – the day Britain declared war with Germany. This forbade ‘aliens’ from travelling more than five miles from their homes, or from living in ‘prohibited areas’. Karl Lorenz, a 25-year-old chef who had been living in York for nine years, was among those caught up under this insidious Act. “He was prosecuted for taking a trip to Harrogate, unaware that he needed a permit to do so,” Helen says.

It is hard to imagine these days: but the city really did seem to have been in the grip of fear. Helen, who along with a group of postgraduate interns from the university has been trawling the city’s various archives for months to find out how the outbreak of the ‘Great War’ affected York, says that the city quickly became famous as a detention centre for German-born civilian prisoners.

Thanks to the efforts of people such as Guy Bedan Alexander, a retired Royal Navy lieutenant, the paranoia quickly grew. Helen and her interns discovered that Mr Alexander actually wrote to the Lord Mayor suggesting the establishment of a civilian ‘secret service corps’ for York, which would “obtain and follow up evidence against anyone of German nationality, and to supply the police with such information as they obtain”.

It was a suggestion that was thankfully not taken up, Helen says. Nevertheless, anyone with a foreign, or foreign-sounding name, felt vulnerable. One man, a Mr W Kitching of Holgate Road, wrote to local newspapers to insist that he “owned no airship or aeroplane with which to assist the enemy”, Helen says.

Another, Joseph Foster Mandefield, a hosier who lived in Monkgate, also wrote to the newspapers to protest against ‘unfounded rumours’ that had been arrested for attempting to poison the city’s reservoir. Poor Mr Mandefield was British born – and of French, not German, extraction.

Before long, York’s population of detained ‘enemy aliens’ had outgrown the Castle Prison and the tented encampment there. To cope with the ever-increasing numbers of detainees, a ‘concentration camp’ – Helen’s own words – was built on the site of the old North-Eastern Engineering Works on Leeman Road.

“The camp had a capacity of 1700 and was surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, but was provided with amenities such as a hospital, shop and hairdressers,” Helen says. It quickly became something of a local spectacle. Crowds of thousands apparently gathered to stare at the prisoners, and even threw food and gifts over the fence.

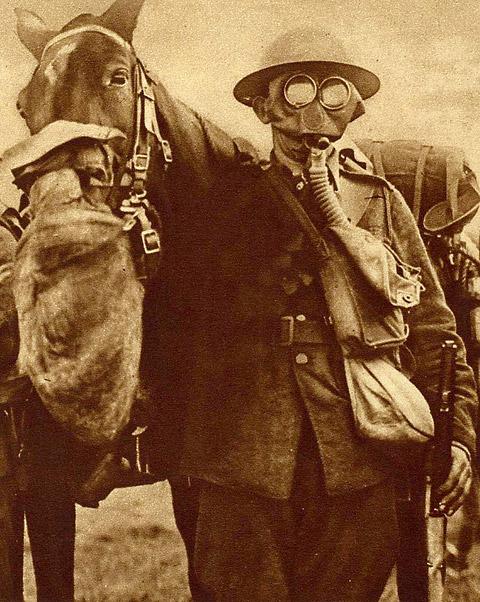

The detention of civilian ‘enemy aliens’ is an episode from York’s comparatively recent past that is little known today. Part of the problem is that the Second World War throws such a long shadow over our memories of the 20th century, Helen says. The picture of the Great War that we do have is largely conditioned more by images of life in the trenches, and by the work of the war poets. We don’t quite realise what a huge impact the war had on life here at home.

With the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the war drawing closer, now is the time to put that right. Helen and her team from the Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past (IPUP) teamed up with York Museums Trust to comb through York’s mass of archives – at the city council, The Press, the Yorkshire Film Archive, the Museums Trust itself, Rowntree’s and elsewhere – to try to build up a picture of what life was like in York during the four years of the war, from 1914-1918.

The first public result of their efforts will be a new walking trail to be launched on Sunday: Experiencing The Great War – York in World War One.

Starting on the steps of the Yorkshire Museum, the walk visits various points around the city centre that have First World War connections – including York Art Gallery, which was pressed into use as both a post office and recruiting office during the war; the Guildhall, which served as a local tribunal and was where conscientious objectors came to plead their cause; and of course Castle Green, where ‘enemy aliens’ were interned.

There are ten stops on the tour in all – ending at the First World War memorial plaque set into the stone arches in Dean’s Park, behind the Minster. The Minster bells pealed out for the first time in five years when the fighting came to an end in November, 1918.

But the price paid by the city and its citizens for victory was high, notes a new leaflet published to accompany the walk. “Thousands never returned, and for those that did, the scars were to last them for the rest of their lives. For those that stayed, their family lives had been shattered. York, and the world, had changed forever.”

• The new York in World War One walking trail will be officially launched at 4pm on Sunday, when a guided walk following the trail will leave from the steps of the Yorkshire Museum. There is no charge, and you don’t need to book. “Just show up,” says Helen Weinstein. Thereafter, people will be able to follow the trail themselves. Thousands of leaflets have been published and will be available free of charge from Visit York, the Yorkshire Museum, the Castle Museum and York Explore Library.

A free app has also been produced to accompany the tour, which will enable you to listen in to a tour commentary on your smartphone as you follow the trail. It can be downloaded from youtube.com/user/Historyworks

There is also a more detailed podcast, voiced by York’s city archaeologist John Oxley, which can be downloaded free from the same address.

Looking further ahead

So far, her team of researchers have just scratched the surface of the material about life in the First World War, Helen Weinstein says.

So expect more First World War stories to appear as we get nearer to 2014.

York Museums Trust, meanwhile, is gearing up for a major exhibition on the Great War that it hopes will run at the Castle Museum. Provided the Trust succeeds in its bid for a £1.3 million Heritage Lottery Fund grant, the exhibition – 1914: When The World Changed Forever – will run at a revamped Castle Museum from 2014-2018.

Helen Weinstein and her team have put together a detailed script, based on their extensive research through York’s various archives, for the podcast which accompanies the new walking tour. It covers everything from zeppelin raids to wounded soldiers back from the front; to the lives of children whose schools were closed to the impounding of ‘enemy aliens’ and then treatment of conscientious objectors.

Here are a few extracts:

• The outbreak of war “The outbreak of the First World War was announced to the citizens of York outside the offices of the Yorkshire Herald building, where there were ‘loud and prolonged cheers… and the National Anthem was sung’ on August 5.” Despite the enthusiastic reception given to the announcement, however, neither the city nor the country at large seemed prepared for a long war. A local headmistress said that when her school had broken up the previous month “none of us even suspected… that Great Britain would join the continental quarrel”. The Yorkshire Evening Press, meanwhile, said that “the normal man cared more about the activities of the household cat than about events abroad”.

• York Art Gallery The central hall and south galleries were requisitioned as a post office and as a recruitment headquarters.

“To many average working men, European politics must have seemed quite distant. Nevertheless, just days after Britain declared war on Germany, an article in the Yorkshire Gazette tells of an average of 200 men a day being signed up here in the city.” Many men held back from enlisting because they had to feed their families. “In order to encourage enlistment, the factories and employers of York agreed that they would continue to pay an enlisted man’s wage to his wife to ensure the upkeep of the families left behind.” They included Rowntree’s and Leetham’s Flour Mill.

• Children Seven schools were temporarily taken over by the armed forces for use as billeting posts, and others were requisitioned for other purposes. “Scarcroft Road School, for example, was closed and used as a post office for some time … School life was thrown into upheaval as groups of children were transferred across the city whilst teachers were encouraged to enlist.” Boy scouts served as military errand boys, and also, in July 1915, helped farmers gather in the harvest. Bizarrely, collecting conkers became a part of the war effort. “In 1917 War Office notices appeared in classrooms and scout huts offering 7s 6d (37.5p) rewards for every hundredweight collected by children…The conkers were used to make acetone, a vital component of the smokeless propellant used for shells and bullets known as cordite.”

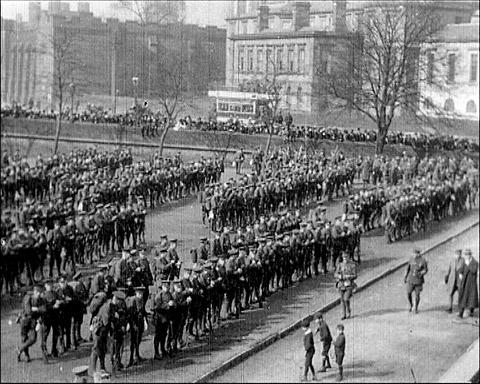

"Images of soldiers of the 5th Battalion York and Lancaster regiment taken from footage held in the Yorkshire Film Archive and reproduced by kind permission of the YFA (www.yorkshirefilmarchive.org )"

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article