In Dickens’ bicentenary year, STEPHEN LEWIS goes in search of the York character said to have inspired one of literature’s most memorable characters.

IN a quiet spot at York Cemetery bordered by a tangle of brambles there is a plot. It is one of many Victorian public graves in the cemetery, but this one has been lovingly tended.

Here lie the mortal remains of 16 people. They all died in December 1865 or January 1866, and what they have in common is that their families were unable to afford private graves. Instead, their remains were stacked one above the other in a deep, narrow-walled pit.

Many of them are children. Infant mortality was distressingly high at the time, says David Poole, the York genealogist and member of the Friends of York Cemetery. “Twenty-five per cent of people buried then were less than a year old: and 45 per cent were under 21.”

The youngest child laid to rest in this grave was a little boy of nine weeks old, William Henry Cussans. Eight others, however, were children of ten or under.

The grave today is marked by a simple slate headstone. But it is not the children whose names are recorded on it. Instead, the name on the headstone is that of Richard Chicken, a larger-than-life York clerk of good family but diminished means.

The details of Chicken’s life that we can glean from surviving letters, parish records, archives and newspaper cuttings show that he was a true character: a man who failed at a string of jobs – everything from clerk to jobbing actor and teacher of elocution – and who never had enough money to support himself and his growing brood of children in the style he felt he deserved.

He was also a prolific writer of letters – usually begging letters – written in a pompous, flowery style. In 1853, for example, he wrote to the Lord Mayor of York asking for a loan of 7/6d. “Pray exercise your benevolence towards me...” he wheedled. Then, as if to demonstrate that he was not simply shiftless, he asked for a job. “I want some employment. Anything however tedious or irksome is better than dependence... I am to be relied on. Chicken and punctuality are synonimous (sic) terms.”

Mr Chicken died in the Union Workhouse in Huntington Road on January 22, 1866, with his long-suffering wife, Louisa, at his side. He was in his mid sixties, the father of 12 children, seven of whom died young.

The reason his name is commemorated on the headstone is nothing to do with wifely devotion, however. It is because Mr Chicken is thought to be the man who inspired one of English literature’s most memorable characters – Charles Dickens’ Mr Micawber.

If you’ve read David Copperfield – or watched one of the TV adaptations – you’ll know instantly who Micawber is: the down-on-his-luck clerk who provides lodgings for the ten-year-old David when he first goes to London. He is a man of wordy dignity immortalised by his simple recipe for economic happiness.

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen six, result happiness,” he tells the round-eyed David. “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty ought and six, result misery.”

Sadly, Mr Micawber was never able to follow his own advice – leaving him, his wife and his large brood of children balanced precariously on the edge of abject penury.

What makes him one of the best-loved characters in English literature, however, is his endless optimism (the unshakeable conviction that something would turn up); his warm heart; his exalted opinion of himself – and his florid language.

At one point, he explains why a position as a legal clerk isn’t suited to a man of his abilities. “To a man possessed of the higher imaginative powers the objection to legal studies is the amount of detail which they involve,” he says. “The mind is not at liberty to soar to any exalted form of expression.”

The way Micawber talks and writes is uncannily similar to the way York’s real-life Mr Chicken wrote in the surviving letters we have – as is his high opinion of himself, unsupported by anything remotely resembling success.

At one point Mr Chicken was employed as a clerk in the offices of the York & North Midland Railway (YNMR) in York. He felt it wasn’t suited to his state of health, and wrote to his boss, Alexander Clunes Sheriff, asking for a transfer. The letter is included in a wonderful article York historian Hugh Murray wrote about Mr Chicken more than a decade ago.

“May it please you sir,” Chicken wrote. “A few weeks ago I ventured… to bring before you the fact that I have for a considerable time suffered from disease in the region of the heart and that very close application to the desk with its accompanying contraction of the Chest operate against me... under the circumstances, if you can give me an appointment where I might have more exercise and less restraint it would be received with appropriate emotion...”

It could almost have been Micawber writing. But there are other reasons for suspecting Chicken might have been the inspiration for Mr Micawber, Mr Murray says. Dickens himself came to visit his younger brother, Albert, a railway engineer, when Albert worked in York in 1847 – in the same offices as Chicken. “So Dickens is very likely to have met him.”

Even if he didn’t, Albert would probably have talked about such a colourful colleague. And the timing is certainly right: David Copperfield was first published in monthly parts in 1849.

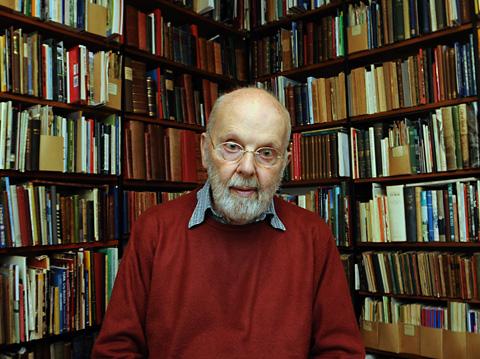

It is all circumstantial evidence, Mr Murray admits, but he is not the first historian to have suggested Chicken may have inspired Micawber. As early as 1930 TP Cooper, in his book The Real Micawber, suggested precisely this.

Ultimately, the evidence is pretty strong.

“Richard Chicken’s orotundity of speech, his circumlocutions, his use of letters in his attempts to relieve his poverty, and his variety of professions and qualifications would all have commended him to… Dickens,” Mr Murray writes in his article Mr Micawber in York.

Even Micawber’s Christian name, Wilkins, has a York origin: it was common slang in the city for anyone who was hard up, Mr Murray notes. “It has its origin in Major Wilkins, an 18th century centenarian who was imprisoned at York Castle for 50 years for debt.”

Now there’s a man after Chicken’s – and Micawber’s – own heart.

Mr Chicken’s life

RICHARD Chicken was born in York on August 6, 1799, the son of the city’s Surveyor of Windows and Taxes, according to York historian Hugh Murray. His father died in 1809, leaving his mother Elizabeth, a wine merchant, to bring the family up.

The young Chicken was sent to Bingley Grammar School, then became (like Micawber) a legal clerk – in Chicken’s case at the Ecclesiastical Court in York. He did not take to the work, and later, in one of his many letters, mourned “the useful money misapplied in my Articles and keep”.

He next tried his hand at being an itinerant actor. His first appearance in York was at the Theatre Royal on April 1, 1824, when he played the eccentric apothecary Dr Ollapod in a play entitled, appropriately enough, The Poor Gentleman.

The reviewer for the Yorkshire Gazette wasn’t impressed, noting that Chicken had “much to learn and to unlearn, before he can attain eminence in his profession. He misplaces the h’s terribly...”

Chicken became a teacher of elocution, styling himself a Professor of Elocution and Lecturer on Defective Enunciation, then briefly a schoolmaster. And by 1847, married and living with his family in St Mary’s Row, Bishophill, he had changed careers again and was working as a clerk in the same railway offices as Dickens’ younger brother Albert. That is when he might have met the famous author.

He found himself without work again in 1852, and over the next few years wrote frequent begging letters to all and sundry.

“Dear Sir, As this is the 6th of August (the Transfiguration of my birth day being 58), Mrs Chicken wishes to indulge me with something nicer than ordinary fare,” he wrote to a Mr Wright on his 58th birthday in 1857. “We shall therefore be mutually obliged if you will allow Quintus [his fifth son] to have 8/– as soon as you conveniently can.”

By this time – Chicken having found and then lost another railway clerking job – poor Quintus, aged just 15, was the family’s principal breadwinner. At that, he was lucky. Five of his brothers and sisters had died in the 1840s, three of them on the same day of pestilential fever. Another sister died in 1854, and yet another, of scarlet fever, in 1863.

Chicken continued to find of bits of work – and continued to write letters – but eventually his long-suffering wife left him, taking the surviving children with her. By January 1865, Chicken had been admitted to the Union Workhouse in Huntington Road, where he was to die. His sense of being superior to his surroundings remained to the end, however.

“The society of idiots, the ignorant, the profane, is not adapted to me – poor Chicken,” he wrote.

At least his wife, despite their separation, was with him when he died. Typically, she could not afford to pay the 4s and 6d for his burial at York Cemetery – and had to borrow the money from an old school friend of her husband.

The letters...

A NUMBER of Richard Chicken’s letters survive, transcribed and seemingly passed down from a contemporary of the man himself. They are not originals, but there is no suggestion they are hoaxes, York historian Hugh Murray says.

Here are a few extracts:

To the Lord Mayor of York, 1853

“Let me experience at your hands that feature in the body of Charity designated Almsgiving. I want some employment, anything however tedious or irksome is better than dependence.”

In a postscript to the same letter, asking for hand-me-downs

“Do you think, Sir, that you have a Coat or Trousers in reversion? Quintus my son will call at your consideration tomorrow.”

To Mr Wilson, Mr Sheriff’s chief clerk, after he had lost his job

“I cannot conjecture why I am to be thrown ‘on my beam ends’... I hope that Mr Sheriff will reconsider his verdict, and allow me to tarry.”

To his boss, Mr Alexander Clunes Sheriff, June 5, 1854

“I have for a considerable time suffered from disease in the region of the heart and… very close application to the desk with its accompanying contraction of the Chest operate against me... Under the circumstances, if you can give me an appointment where I might have more exercise and less restraint it would be received with appropriate emotion…”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here