A HUSHED evening, deep in a fold of the Yorkshire Wolds. Somewhere, a partridge is chuntering to itself. A stock dove flaps into a tree; a pheasant gives an alarm call.

Above us on the upper slopes of the valley sheep are grazing in the late light. Down here, deep in this grassy valley, however, all is still.

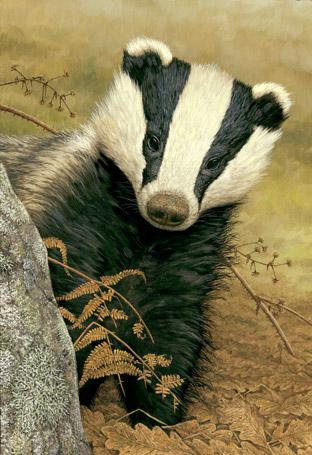

We are sitting in a hide five feet up in the branches of a tree. Below us, sheltered by a row of imposing ash trees that snakes along the valley floor, is a badger sett.

It’s approaching 9.30pm. Dusk is drawing in. We expected the badgers to have put in an appearance before now, but something has spooked them: perhaps our own scent, drifting down from the hide.

“They’re always timid,” says Robert Fuller, in a whisper, “especially for the first 15 minutes. Sometimes they will just come to the entrance of the holes, scenting and hearing. You can sometimes see their striped faces looking out.”

Not yet, though. We lapse into silence again, lulled into a deep sense of peace by the quiet beauty around us.

Then Robert touches my arm. “There’s the first one!” he whispers. “At the top hole.”

I scan my binoculars up, and there it is. A flash of striped snout, and then the head emerges above a shaggy, bulky body clothed in silver-grey fur.

The badger is cautious: head upright, sniffing, scenting the air from every direction. Then it relaxes, and scurries on to the broken earth and gnawed logs at the entrance to the sett. It is quickly followed by two more: another adult, and a cub.

The cub is bursting with energy, eager to play. It chases its tail, then bounces into the air, before turning back to the two older badgers in a mute appeal for them to come out and join in the fun.

But they’re still cautious, and when one of us in the hide above inadvertently makes a noise, they quickly retreat. One of the adults grabs the reluctant cub by the scruff of the neck and whisks it away down into the hole.

Robert laughs quietly. They’re particularly alert tonight, he says: spooked by the flapping dove, and even the pheasant. Last night they were all out – all six adults and three cubs – playing happily before heading off up the hill to forage. “They can sometimes roam up to three to four fields away at night,” he says. “It depends how good the feeding is. Like with all wildlife, the range depends on the food.”

I’ve joined Robert here in this remote corner of the Wolds for an evening of wildlife spotting. He makes for a wonderful guide, as you would expect of an artist who has made a hugely successful career from photographing and then painting, in exquisite detail, the wild creatures that live around him.

It’s more than just his artist’s eye for detail that makes him such a good guide, though. He grew up on a farm on the edge of the Wolds, and he’s walked these hills and valleys all his life. He knows every tree, every gate, every badger hole. He and his older brother, David, spent their childhood out in the open, ferreting, searching out nest sites, and watching the birds and wild animals around them. It was, Robert says on his website, an “idyllic rural childhood in the truest sense of the word”.

He has about him that deep, quiet reserve of the true countryman: the ability to be comfortable with silence, and with the wide skies and open landscape around him.

You get the impression, sometimes, that he feels more comfortable out here than he does trying to deal with the more complicated world of men.

He was dyslexic at school and he left at the age of 16 with a reading and writing age of nine.

Read one of his beautifully written nature columns in the Gazette and Herald – The Press’s sister newspaper – and it’s extraordinary to think he didn’t gain the confidence to write until just a few years ago. “I left school thinking I couldn’t do anything,” he says.

Except draw and paint, that is. He’d been sketching the animals he observed ever since he was young; and at school in Pocklington, art was one of the few things he was good at.

It seemed obvious, therefore, to go to art college when he left: first in York, then in south Wales. As soon as he left college, he returned to his beloved Wolds and set up in business as an artist, quickly becoming successful. His former school is proud to have him as an old boy now, he says poignantly.

It took him a long time, however, to overcome his fear of the written word. It was having his daughter Lily, now aged three, that was the spur. “It was reading to her.”

Lily is busy in the beautiful garden of Fotherdale Farm, where the Fullers live and where Robert has his gallery, when I arrive for my evening of wildlife watching. She’s deadheading some chives that have gone to seed, under the watchful eye of mum Victoria.

Thixendale is less than a mile away: but here, perched at the head of a deep Wolds valley, we seem in the middle of nowhere.

We climb into Robert’s Toyota 4x4 and head off down a narrow lane. We’ve barely started when Robert pulls to the side of the road under the shade of a beautiful elm. There are splashes of white bird droppings on the road. “They’re the giveaway,” Robert says.

I’m puzzled, wondering what he means. He points casually up into the branches, and my heart leaps into my mouth. Sitting there, watching me with a steady, unblinking intensity, is a beautiful bird; big, and tawny, with a speckled chest, black, unlinking eyes, and a wickedly curved beak. A tawny owl.

“That’s the female,” Robert says. He gestures at another tree. “And there’s four chicks, up there.” I look, peering between the branches and the dappled green foliage, and there they are, watching me with that same unmoving intensity: four large, softer looking birds, in paler juvenile foliage.

“And that’s the male,” Robert adds, indicating another bird perched on another branch, watching, watching. Its body is rock still, but its head flicks for a moment, and the eyes blink.

He’s not the friendliest of tawny owls, Robert says. “He’s attacked me several times. Last year, he grabbed me on the shoulder, and I had four talon marks on my back.” Another time, when Robert was climbing a tree, the bird attacked his head. Luckily, he was wearing a helmet. “It was like being hit on the head with a brick! I saw stars!”

Tawny owl: photo by Robert Fuller

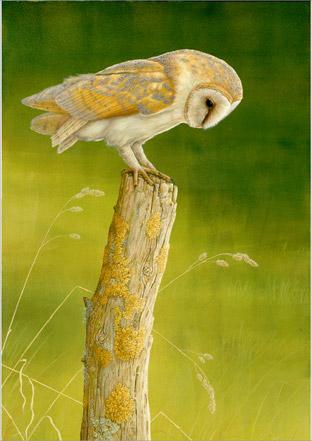

Painting of tawny owl on lookout by Robert Fuller

Barn owls are much less fierce, as I soon learn. We head off the metalled country road, and down a narrow, grassy valley, opening and closing farm gates as we go. A row of ash trees is dotted haphazardly along the valley floor. Robert eases the Toyota to a halt beneath one of them, unships a ladder fixed to the roof, and leans it against a tree. There’s a large nest box wedged between branches a little way up. Barns owls, Robert says; he helped feed them during the long hard winter, to ensure they’d survive. “We lost a lot of barn owls and little owls over the last couple of winters.”

He climbs to the nest, reaches in, then comes back down with a fluffy baby owl clutched in his hand. “This one’s a female,” he says, “about three to four weeks old.” I stroke the silky white down that covers much of the bird’s body. Robert stretches out a wing gently. “Look at the feathers coming through,” he says. And so they are, beneath the down.

I wonder where the parents are. They will be somewhere nearby, watching, Robert says. “You don’t leave your children, do you?” I know he’s thinking of Lily.

You don’t: which is why, after those stories of attacking tawny owls, I’m worried about the parent barn owls.

No need, Robert says calmly. “Barn owls never attack you, not even to protect their chicks.”

We continue: along the valley bottom, up over a flanking hill, along another deep, grassy valley, opening and closing gates. Robert points out hares leaping out of our path; a clutch of kestrel chicks on the branch of a tree; little owl pellets scattered below another ash tree. They’re full of fluff. “This one’s been eating mice,” he says.

Then, deep in the valley bottom, with dusk approaching, we come to the badger sett. Robert drives the Toyota out of sight along the valley floor, unships his ladder, and we climb up to the hide he built himself five feet up in the tree.

We settle in to wait, the silence companionable, until the first badger appears in the entrance to a hole, followed by that playful cub, bouncing and chasing its tail. It’s the perfect end to a magical evening.

• The Robert Fuller Gallery, at Fotherdale Farm near Thixendale, is open every day including Sundays, from 11am-4.30pm. For more information visit robertefuller.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel