York has one of the finest collections of archive books in the country. MATT CLARK meets the librarian who cares for some of the most important ones.

SARAH Griffin opens a page of the King James Bible. This one was used for worship in York Minster from 1611 and within its pages are intriguing ponderings, such as one written by someone who simply called himself Richard, but who was clearly a man of the cloth. “Oh God why hast though forsaken me,” he inscribed poignantly on the frontispiece to Zechariah.

“We have six copies of KJB,” she says. “But this one is among the most exciting books in the library, because of its Minster provenance and for insights like this we get from handwritten notes.”

Sarah has been appointed special collections librarian at the University of York and Minster Library and in her job, she reads the story of the book itself. It’s a mystery thriller, but one written between the lines – or even above them.

“On some of our other books the previous owner has written what he thinks to it, or where he bought it and that is useful to us because it gives information about the period in which they lived.”

Take the post-Reformation prayer book, again with a Minster binding. It tells of the Church of England’s pangs of guilt, with St Thomas a Beckett’s name scored through and all references to papal symbolism defaced. Yet burning books, it seems, was still an act of heresy; still an act too far.

Sarah says the knowledge she gains from these annotated words is priceless, but with a wry smile she admits if she saw someone doing it today, she would give them hell.

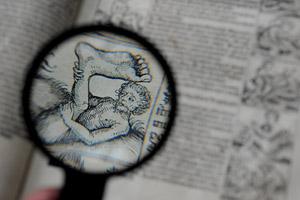

Many of the Minster and university books are far too precious for personalised graffiti. Such as the Pica, York’s oldest surviving printed book, or the extraordinary Nuremburg Chronicle, with its bizarre woodcuts.

Then there are some exquisite early atlases. Among them Abraham Ortelius’s first world atlas, dating from 1570, and Yorkshire-born Christopher Saxton’s first survey of the United Kingdom, from 1577.

Both are things of great beauty, but they spark another interest. These are simply compilations of previous work, but back then it was perfectly acceptable to put your name to someone else’s endeavours.

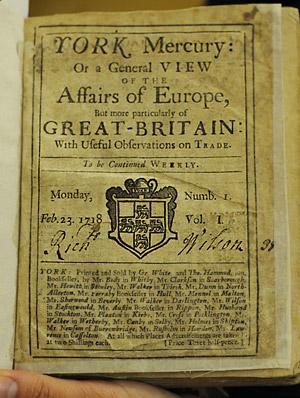

“When printing began, plagiarism was flattery; it wasn’t considered an issue at all. Take the York Mercury, which was almost all national news taken from London papers that arrived by stagecoach. But that wasn’t considered plagiarism either. John Speed is another good example although in fairness, he does acknowledge what he is doing.”

Everyone was simply trying to reach the same goal: the same quest for knowledge.

One of Sarah’s jobs is to allow public access to precious books such as these. There are issues surrounding this, but she is determined such books do not become museum pieces.

Anyone in York can borrow books from the Minster Library Loans Collection where, understandably, many are theological works. But there is much on history, art and architecture plus an outstanding collection devoted to stained glass. For £25 a year you can borrow up to six books for three weeks.

A more tempting prospect might be to make an appointment in the reading rooms to view those books so precious they are held in the vault. Works such as the complete set of York printer Thomas Gent’s guides from the 18th century or the first edition of The York Mercury, the city’s first newspaper, dated February 23, 1718.

The most fascinating are a series of tracts from the Civil War, which represent the earliest examples of English printed propaganda.

“With the King in exile, broadsheets were published away from London, including York. They are interesting because for the first time we saw a great propaganda war. Both sides used these little pamphlets as rallying calls and they could produce them very quickly. It was a chance to publish their slant on how the war was going within a week.

“In the 17th century, that was fast. Before the printing press it couldn’t have been done.”

For the first time people were able to get involved and keep up to date with volumes such as ‘True Newes from York’. Even though it was anything but. There are 120,000 important works in the Minster Library archives and another 10,000 at the university, but while the information held within their covers is priceless, so too is the human story they tell.

“Within the past 20 years, there has been a move away from books being just paper with words printed on them because with online books you can easily download their content.

“So the interest now is what makes the particular book you have in your hand special. It might be because it was owned by someone in particular. We, for example, have a prayer book owned by William Laud, the archbishop beheaded during the Civil War, and that is what makes this copy so fascinating.”

The treasure trove Sarah is responsible for is breathtaking and it comes as no surprise when she says York has the only accredited cathedral museum in the country.

She is especially proud of a couple of upcoming projects.

Firstly, the room holding the Loans Collection will be closed and revamped in July to make it more user-friendly. Sarah hopes this will allow it to be better used.

Then there are the cases about to be installed in the upper hall thanks to a grant from the friends of York Minster. They will allow precious books and manuscripts to be brought to York; ones which until now could not be afforded the required protection.

Family aside, Sarah has two loves in her life: books and history. Her role is to not only preserve the masterpieces of the past, but promote the ones of future.

Something she is acutely aware is under threat.

“There is nothing quite like the tactile experience of sitting with a book. I was amazed that when my children were quite small they were looking through an encyclopaedia for something. So I said use the index, but they had no idea at all how to use one.

“We are losing those skills. The first thing children get at school is a laptop and it does everything for them. I worry that we are too reliant on computers and the internet.”

But literacy is not only being able to read and write, it’s being able to structure a sentence, to spell without relying on a computer and Sarah is concerned that regaining the reading habit would go a long way to redress this country’s lamentable literacy figures.

“I’m not averse to Kindle; it must be very useful when you go on holiday, but I don’t see it replacing books. They are lovely things and people like to have them on their shelves. We also enjoy just dipping and browsing through them.

You can’t do that with a Kindle, it’s just not the same.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here