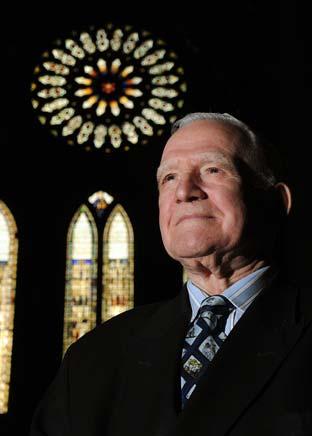

ALL his life, Peter Gibson has lived in the shadow of York Minster. The great Gothic cathedral is visible from the window of the small sitting room of his tiny Georgian mews cottage, in Precentor’s Court. It can be seen from his bedroom above and from the attic above that, where he still sits to hand-write his lectures and papers.

Outside his old-fashioned wooden front door, the Minster’s West Face rears up in its full Gothic majesty: inspiring, imposing and a little overwhelming.

Mr Gibson has given his working life in the service of this cathedral and a little part of him is woven into its very fabric.

As superintendent and secretary for many years of the York Glaziers Trust, he has worked on every one of its more than 120 windows. He has twice supervised the restoration of the magnificent Rose Window – most famously following the great fire of 1984, which threatened to destroy it. And there is even one window which bears his own likeness.

It is a medieval Jesse window in the nave, showing the family tree of Christ. It was repaired in 1950, as the Minster’s stained glass was being replaced after the war. The Dean at the time, Dean Eric Milner-White, had been able to piece together most of the pieces of the window, but there was no central figure of Jesse.

The great stained-glass painter Harry Stammers was commissioned to paint a new Jesse; a young glazier named Peter Gibson happened to be the only person in the workshop at the time who could pose as a model.

“So I climbed up on a bench in the workshop and posed in various positions,” he says. “It was the one and only time I was a model.”

Mr Gibson is famously unwilling to be drawn on the question of his age, but it is not too hard to work out. Sixty years ago, he was a young apprentice working to restore the stained glass taken down during the war: so today he must be at or about his 80th birthday.

It has been a life well-lived. He has won international acclaim and renown for his work on the Minster’s stained glass, and on the stained glass in other York churches. He has lectured all over the globe, and in every county in England; he has been twice honoured by The Queen: with the MBE in 1984, and the OBE in 1995.

In the year 2000, he was voted second only to the great Dame Judi Dench as ‘Millennium Person of the Present’ by readers of this newspaper. And next year, he will receive the highest honour York can bestow: the Honorary Freedom of the City. That will put him in the company of luminaries such as the Duke of Wellington, Sir Winston Churchill, John Barry and Dame Judi herself.

Yet, extraordinarily for a man of such renown, he has lived all his life in this one same house, tucked away in the shadow of the Minster.

His parents came here soon after the end of the First World War. His father, William, was a private in the Royal Scots Greys, and came to York with his regiment. He met and married a York lass, Mary. “They had nowhere to live,” Peter says, “and they heard that some Minster properties were available. They went to see the estate agents, and asked if they could be considered, and the answer was yes.”

Peter’s elder sister, Ellen, was born; then Peter himself, and the family continued to live here, in this quiet, elegant mews right in the heart of the city.

This house has framed his whole life. It was here, when he was a young lad about to leave Nunthorpe School, that Dean Milner-White came to visit him.

He had got to know the great dean through being an altar boy at the Minster. The dean had already invited him on a tour of the stained glass workshops on the afternoon of the day Peter was to leave school.

The following Sunday, there came a knock on the door of the small Precentor’s Court cottage. It was the dean, asking Peter what he planned to do the next day.

“I had to admit that I was going to the Labour Exchange to see what jobs were available,” Peter recalls.

Instead, he found himself being invited to turn up at the stained glass workshops the next morning to start an apprenticeship. He had found his calling.

But he continued to live at Precentor’s Court. His father died, then his mother, and, a few years ago, his beloved sister Ellen.

Neither had married and they had shared the same house all their lives. She was, he says, a very gentle woman, and they were very close.

“Having been brought up with someone like my sister, one gets very attached to them. Probably more so than if they had left home and married.”

But when those you love pass away, you carry on, he says.

“There is a lot of history in this house. But they [his family] were very proud of me and my work, and I would like to think that they are looking down on this recent announcement [about him receiving the Honorary Freedom of the City] and I hope they are pleased with it.”

He has never been tempted to move, he admits – not from York, and not from this house.

Yes, travelling is important and gives you new, wider perspectives. But why would he want to leave York?

“I live here, and I look out of the window, and there it is, the Minster. It is one of the greatest buildings in the world. People cross oceans, cross the world, to come and see it. And there it is.”

When he travels the country and the world to give the lectures for which he is famed, people often ask where he comes from. “I say ‘I come from York’ and they say ‘ohh!’ and they think I am so lucky to live in a city like York.”

It is a rare day, he says, when he walks out in the city’s streets and doesn’t meet someone he knows, or who knows him.

And then there is the knowledge of what he himself has given to York.

The Minster, he says, is a ‘great national treasure of stained glass.’ “And I have had the great privilege of working on every single window.

“I walk through York, and in Coney Street there are the windows of St Martin’s, some of which I restored. And there is St Denys: I worked on windows there. And All Saints in North Street: I spent three years working there. And every day I pass the Minster, and I cannot help but look up – and there are the windows that I have worked on there. I could never leave York. It is a part of my life.”

How fitting, then, that the city he loves, and to which he has given so much, should have chosen to honour him in its turn.

* WHEN he is formally conferred with the Honorary Freedom of the City next year, Mr Gibson will join a small but very select group.

The earliest person on record to have received the honour was Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and designer of York’s Assembly Rooms, in 1737.

The Duke of Wellington has also been conferred with the honour, as have Sir Winston Churchill, John Barry, Dame Judi Dench, Dame Janet Baker, Professor Sir Ron Cooke, Dr Peter Addyman and Dr Richard Shephard.

But who are the Freemen of York?

The tradition of Freemen goes back to early medieval times, says Peter Stanhope, pictured, a member of the Gild of Freemen of York who nominated Mr Gibson for the honour. A Freeman was a former serf who had been made free and granted the right to work for himself rather than for a feudal master.

Such Freemen formed themselves into gilds – builders, cordwainers, butchers etc – and came to dominate town life.

“Up until 1835, the city was controlled by a council of the Freemen of the city and Aldermen of the city,” says Mr Stanhope.

There were three ways that you could become a Freeman: by birth – if your father, grandfather or great-grandfather was a Freeman; through apprenticing yourself to a craftsman or tradesman who was a Freeman; or by purchasing a ‘franchise’.

“That amounted to buying your way in,” says Mr Stanhope.

Being a Freeman conferred three key rights: to do business in York; to hold public office in the city; and to vote in elections.

The power of the Freemen began to wane when, in 1835, an act of Parliament extended voting rights to others. Today, there are about 5,000 hereditary Freemen of York, who can pass on the right to be a Freeman to their children and grandchildren. Many of them do not live in the city.

Mr Stanhope, who is a hereditary Freeman of York through his mother’s family, admits that today the title confers few privileges. “But it is an honour: it’s part of our heritage. I’m very, very proud to be a Freeman of the City.”

The Honorary Freedom of the City, which is being conferred upon Mr Gibson, is rather different to the hereditary Freedom. It is a special honour conferred on those who are not Freemen by hereditary right. Those who have been conferred the Honorary Freedom of the City can become members of the Gild of Freemen – but only in their lifetime. They do not pass that right on to their descendants.

Nevertheless, it remains the most important honour the city can bestow. There are three grounds on which the honour can be conferred. It can be given to those who are loyal servants of the city; to distinguished people; and to Royalty. “Successive Dukes of York have been made Honorary Freemen of the City,” says Mr Stanhope.

Mr Gibson will be in good company.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel