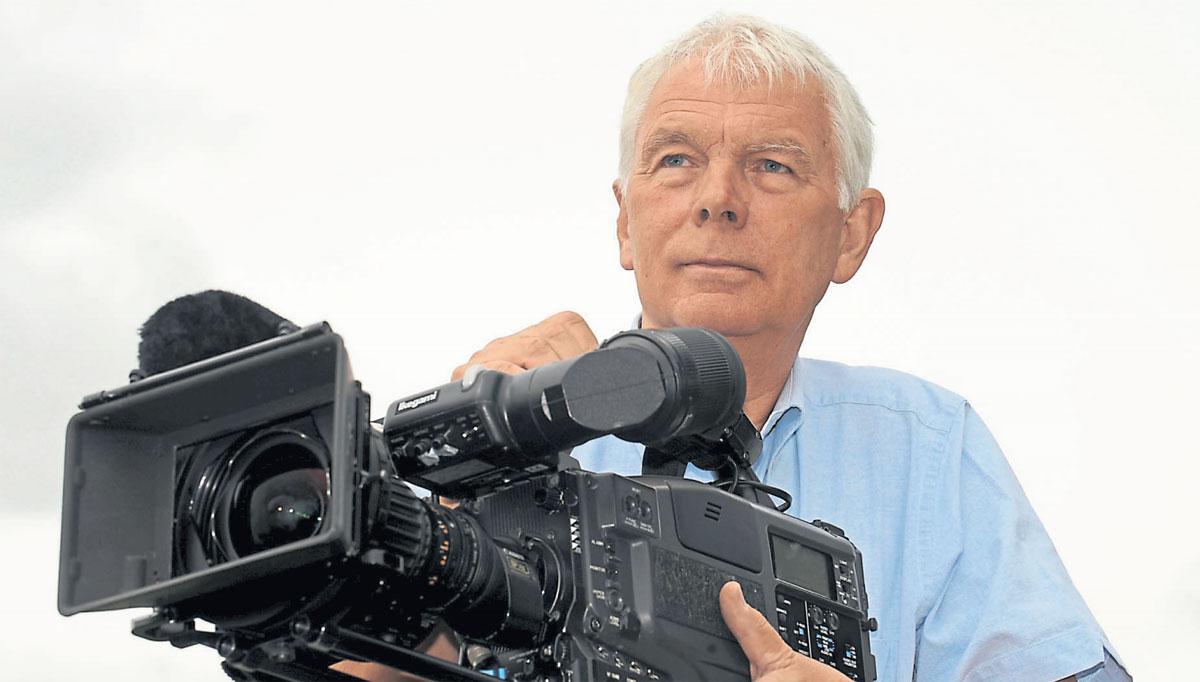

Award-winning TV cameraman Keith Massey talks to STEPHEN LEWIS about John F Kennedy, the Iron Lady, filming the Queen and why it is essential that journalists are free and able to do their job.

PEOPLE of a certain age often remember exactly what they were doing when they heard John F Kennedy had been assassinated. Keith Massey is no exception.

He was an 18-year-old Yorkshire Evening Press photographer, and was attending the Army Northern Command's annual bash for press and TV at the Royal York Hotel.

He had just managed to blag a press trip to Borneo off an Army press officer. "I'd asked him if there was any chance of covering army exploits abroad, and he said: 'what about Borneo'? I said 'yes, please!."

He was still celebrating the prospects of an overseas trip when someone came into the room.

"He said 'ladies and gentlemen, I have an announcement to make. The President of the United States, John F Kennedy, has been assassinated'," Keith recalls.

So it is that the death of Kennedy has been forever associated in Keith's mind with the beginning of his distinguished career as a TV cameraman. Because it was on that trip to Borneo, the following February, that he shot the grainy footage that was to be his first film footage shown on TV.

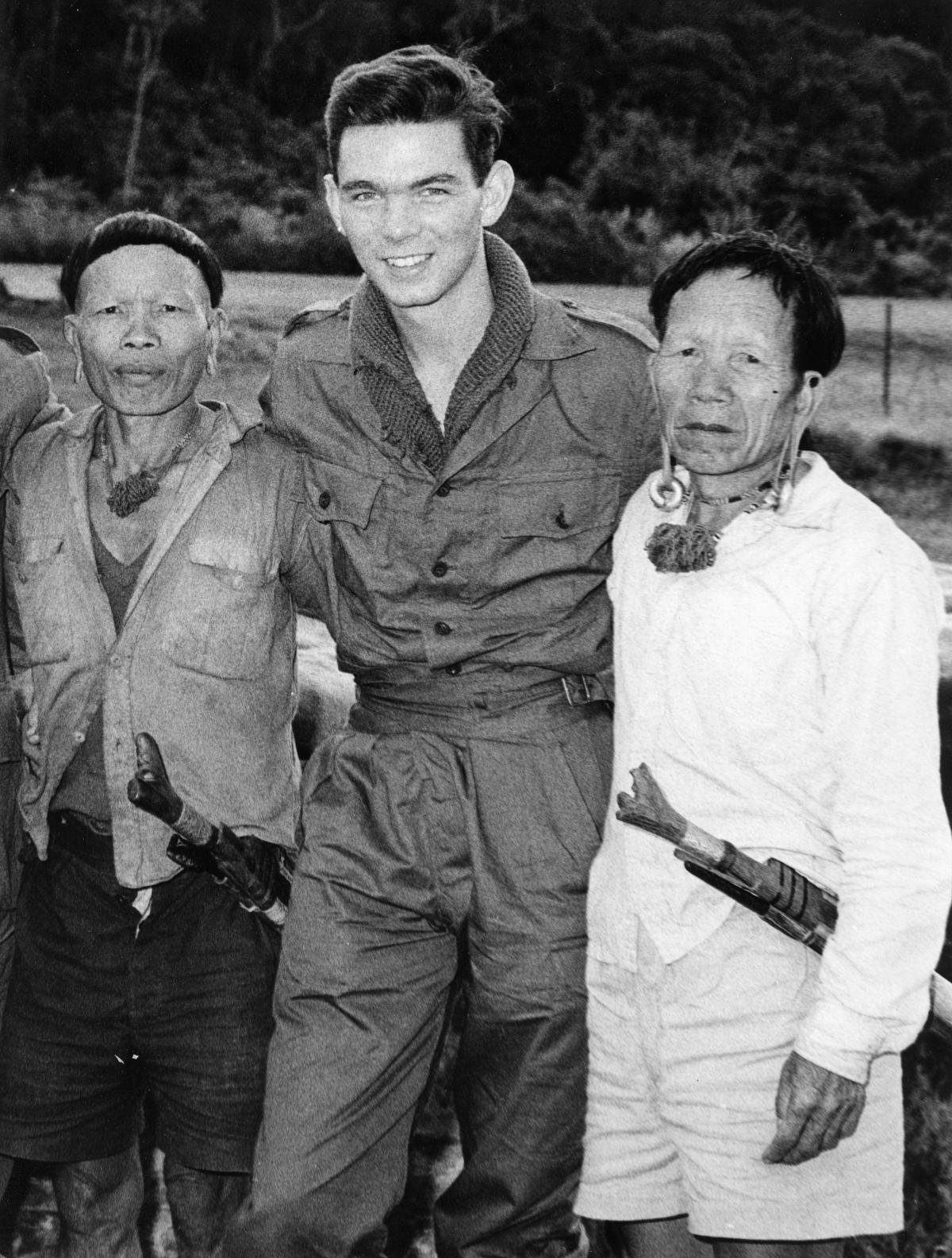

In 1964, Borneo was at the centre of a 'conflict' between Sukarno's Indonesia and the fledgling state of Malaysia. British troops and aircraft had been flown into the former British protectorate of Sarawak in Borneo's northern highlands: and Keith was sent to join them.

He found himself sleeping under silk parachutes in the jungle with SAS troops: and recording a 'hearts and minds' operation in which British forces provided transport for members of the Kelabit tribe.

It was quite a culture shock for a 19-year-old Yorkshireman. The Kelabit lived in longhouses. Their womenfolk wore so many earrings that the lobes of their ears were stretched, Keith recalls.

"And the men of the tribe had been killing Japanese in the last war and shrinking their heads. They had them up in the longhouses..."

It was these people that the British were transporting from longhouse to longhouse in Westland Whirlwind helicopters, flying 50 feet above the treetops across seemingly endless jungle. Keith, a founder member of the York Gliding Club, went along to capture photographs. And on one memorable occasion, when the helicopter's pilot found out he was an experienced glider, he was invited to take the controls.

"I thought I did quite well," he says. "But when we landed an airman said, 'It was a bit rough, sir. Some of the passengers were sick!"

While in Borneo, in addition to taking photographs for the Evening Press, he used a second-hand Keystone film camera to shoot footage of the Kelabit people.

When he got back to York, legendary Evening Press entertainments writer Stacey Brewer, who had a five minute slot on Granada TV, arranged for a clip of his film to be screened – to the accompaniment of Frank Sinatra singing Come Fly With Me.

With a start like that, it wasn't long before Keith was working as a TV cameraman. He joined the John Pick news agency, and in 1966 became the first person at Pick's to begin filming for TV, in one case memorably filming the Doncaster St Leger for national TV on a clockwork camera which could only film for 25 seconds.

He then turned down the chance of a job as a Daily Mail photographer to do a couple of shifts a week as a TV cameraman for the BBC in Yorkshire.

It was a precarious existence, especially as he was newly married, with a mortgage. But it was TV that he loved.

He'd been spellbound by it ever since watching the Queen's Coronation in 1953 on the family's nine-inch black-and-white screen. He was an eight-year-old boy growing up in Holgate. "And for the first time it opened up the world in your living room."

The late 1960s, when he was first breaking into TV, was a time when pioneering broadcasters such as David Attenborough and the underwater film-makers Hans and Lotte Hass were pushing the boundaries of what television could do. It felt like the future, Keith says - and he wanted to be a part of it.

Getting a full-time staff job at the BBC proved impossible, however - so in 1970, he went freelance. He spent the next 43 years as a freelance TV cameraman, working on news and documentaries for the BBC and, later, Sky, and even spending four years as a cameraman on TV soap Emmerdale.

He packed an awful lot into those four decades. During the First Gulf War, he got a rollicking from Kate Adie for failing to capture footage of an incoming strike by five Scud missiles – he'd literally just arrived in the country and was caught unprepared.

He joined Look North reporter Cathy Killick to film a report on the Holy Land, and had a run-in with a Number 10 press officer after filming Margaret Thatcher on her battle bus.

He and his colleagues from Look North had been told they'd be able to stay on the bus all the way to Harrogate, Keith says – but the press officer decided they had overstayed their welcome. He started ranting at them, until the Iron Lady herself intervened. "She said 'now, now, now, now, they are my guests, they are fine," Keith recalls.

In the early 1970s, he found himself filming in a Roman sewer beneath King's Square with Blue Peter's Valerie Singleton. And in the 1990s he spent a week training in a Tornado jet from RAF Leeming in preparation to film a flight over Buckingham Palace to mark the Queen's birthday.

It was quite a day. "I was flown in a Lancaster Bomber, squashed in the cockpit, over Buckingham Palace and straight down the Mall with a Hurricane on one wing and a Spitfire on the other," he says.

His most traumatic assignment came quite early in his career, on June 1, 1974 when he was sent up in a helicopter to film from the air the devastation caused by the explosion of the Flixborough chemical plant in North Lincolnshire, which killed 28 people. The news film Keith and his team shot won him the first of his many Royal Television Society awards - but it haunted him for years afterwards.

In 2010, Keith was presented with a Royal Television Society Lifetime Achievement Award - and in 2012 he was elected Chair of the Guild of Television Cameramen.

He finally stopped filming for TV at the end of last year: but he is still, at 69, passionate about the industry the has devoted his life to, and keen to use his role as Guild chairman to do what he can to protect standards, and defend the rights of journalists to do their job.

Earlier this year, he lobbied Prime Minister David Cameron to put pressure on the Egyptian government for the release of Australian journalist Peter Greste and his Al Jazeera news crew, who have been imprisoned in the country's Tora prison.

"We call on these journalists to be released forthwith by the government and military authorities to demonstrate to the world that the new emerging Egypt honours freedom of speech in a democratic manner," he said, in a hard-hitting Guild statement passed on to Number 10 by York Outer MP Julian Sturdy.

The intimidation and imprisonment of journalists going about their legitimate activities can never be allowed to go unchallenged, Keith says, speaking from his home in Acaster Malbis.

"Peter Greste and the Al Jazeera crew have been in prison since December - but it could be any one of us that work in news," he says.

"All you are trying to do as a journalist is convey the truth, with a camera, a pen or a microphone. In some situations, you hope that the presence of the world's media can have a calming effect: if they are witnessing atrocities, then these tend to get stopped. The freedom to actually do that job is something basic. Egypt are hopefully in the first stages of democracy, but it doesn't help when they try to silence the media."

Views of a TV veteran

KEITH Massey has loved working with the BBC throughout his decades-long freelance television career.

“It has been my life,” he says.

But there are things about the corporation he finds deeply frustrating.

He has huge respect for the creative staff who make BBC programmes and he has always had a good relationship with staff at all levels in the north of England.

But there is a problem with the culture of BBC management nationally, he says.

“They have been running it (the BBC) like a 1930s Whitehall department.”

The recent BBC spoof WIA made for painful viewing.

“It wasn’t a drama, it was a documentary. I looked at it and I couldn’t laugh, because you knew it was true.”

Mr Massey says the licence free has left BBC management insulated from the real world, wasting money on bureaucracy while cutting spends on current affairs.

“There is no penny-pinching when it comes to drama or the wonderful wildlife programmes the BBC is rightly famed for.

But, despite major improvements in equipment, standards in current affairs are falling,” he says.

“Film crews which used to include five or more people (including cameraman, assistant cameraman, sound recordist and lighting man) have now been reduced to just a single cameraman.

“There is no lighting person, no assistant cameraman to help carry kit around. It is just one person trying to do it all.”

Training of film crews also seems to have been forgotten, he says. The result of all this?

“This country has an amazing history of documentary making, and we’re just throwing it away.”

As to the BBC licence fee: he thinks it still represents good value at just £145.50 a year.

“But is the Licence Fee system fit for purpose in 2014? It can’t be right or healthy that 150,000 people are dragged through the courts and some going to prison... for watching television.”

The Press contacted the BBC for a response to Keith’s comments. A corporation spokesman said: “We don’t recognise this characterisation of the BBC.

“With programmes like Sherlock, Doctor Who and York Minster, services such as BBC iPlayer and a global, national and regional newsgathering operation we’re concentrating on what’s important to our audiences in Yorkshire and beyond.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel