Yesterday Walter Stead, one of the few remaining survivors of the Second World War’s Death Railway, told us how he toiled in jungle heat to construct the Burma line. Today Walter tells MATT CLARK how he became a survival expert.

AS a prisoner of war Walter Stead was regarded as expendable labour because Japanese military culture considered anyone who surrendered to be worthless.

Life was horrific with daily beatings, little water and meagre rations.

Mr Stead, of Acaster Malbis, partially lost his hearing after a particularly savage beating with bamboo rods and at one point he weighed no more than seven stones.

In Burma it wasn’t a question of survival of the fittest, it was the cunning who survived. And Mr Stead was a survivor. One day, when each prisoner was given six onions to eat from a consignment that had gone off, he ate two and planted four.

Within three weeks there were green tops to cut off, which not only made his dull bowl of rice a tad more interesting, but added vital vitamins, calcium and iron to his diet.

“I also stole a water buffalo. The Japanese seemed to go along with the idea, so I took it to the cookhouse and we all got a share. It was a very unusual incident; a bit like the Christmas truce football match, I suppose.”

Then there were nightly forays out of camp to native villages in search of food. Technically Mr Stead was escaping and if caught would be shot or beheaded.

That said his captors were usually unaware of such nocturnal wanderings. Being pursued by large snakes was the biggest worry.

Until one night, when it seemed his luck had changed.

“They spotted me and I was this far from being shot. The guards shouted ‘kuru’ – come here. Well I thought bugger that, my plan now is to get back into the camp.”

So he ran and scraped and crawled, all the time looking for a safe way in. The guards saw him in the jungle a couple of times, but eventually Mr Stead managed to sneak in by the latrines.

He was immediately arrested and taken to the camp commandant.

“Well it turned out to be the most fortunate and most unfortunate day of my life, because he spoke English. He was the only Japanese I ever met that did.

“I was inside the fence when they picked me up and I said I’d only been to the toilet. Then they found my shirt outside, so I had to own up.”

After an hour of interrogation the officer still hadn’t decided what to do. But as Mr Stead was taken to a makeshift cell, the guard told him he would be shot the following morning.

“I was tied up all night in a shed and had to lie on a stack of rubber sheets, all the time knowing I was going to be killed.

“Every minute was an hour that night.”

But it wasn’t a firing squad that called. Instead, a guard accompanied by a colleague was sent. And he had some unbelievable news.

“‘You’re the luckiest man alive,’ I was told. ‘They’ve had people speaking on your behalf all night and they rescinded the death penalty’.”

IIt was almost unheard of for an escapee to be spared. Up and down the line many others weren’t so lucky. “I once saw someone who had been recaptured beaten to death in front of me. The guards tied him up, put him face down on the ground and beat him with bamboo rods until he was almost a jelly. It was just terrible.”

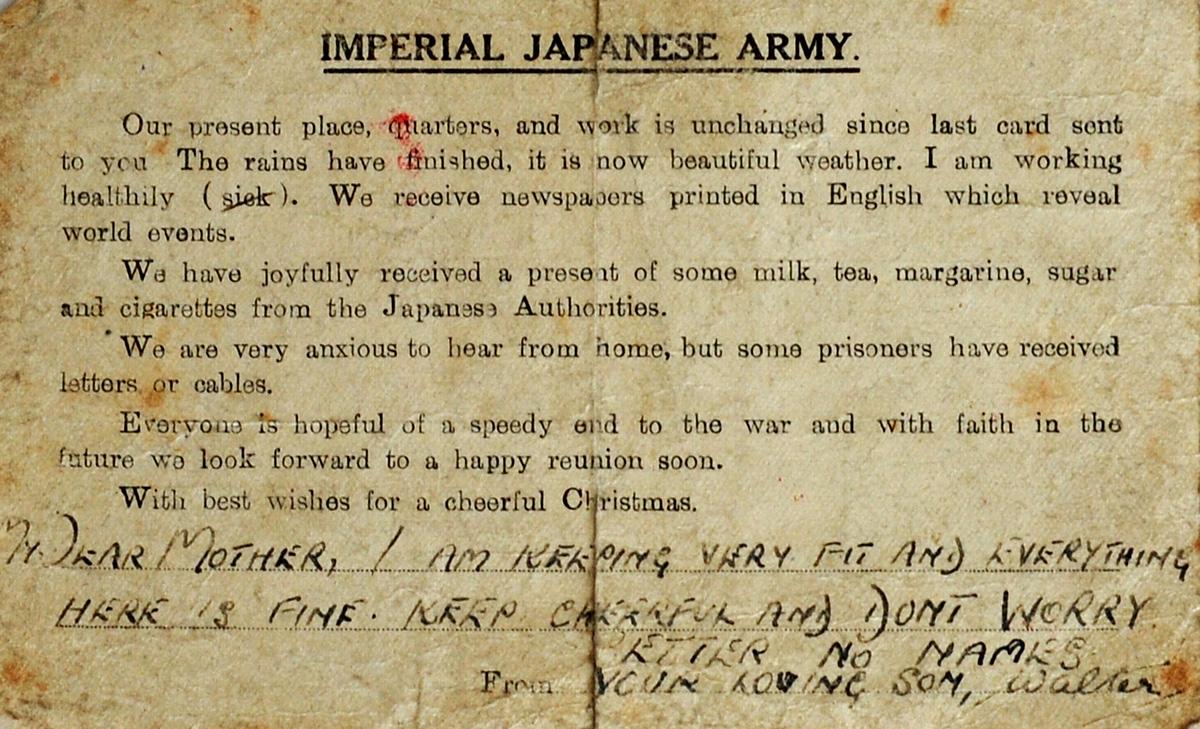

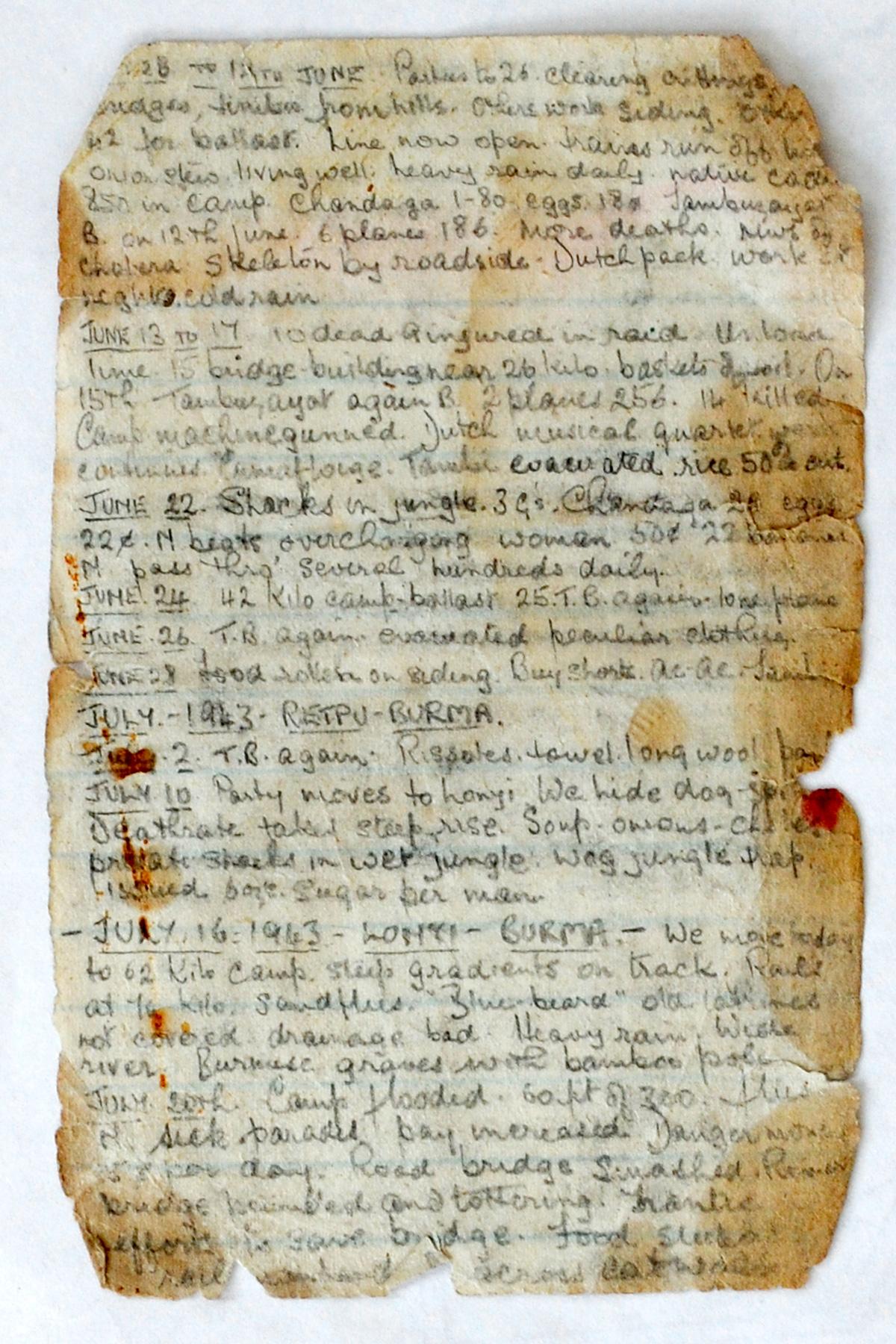

Keeping a diary also attracted the death penalty, but again that didn’t stop Mr Stead. As the railway was built the men moved from camp to camp and each time he had to find somewhere new to bury his journal.

In it he diligently recorded the day’s horrors juxtaposed with more mundane facets of daily life in a prison camp: ‘Aug 29. Soap issued… Recover clogs... Pepper in soup… Body awaits burial… Clements dies dysentery.’ Mr Stead says life didn’t improve after the final sleeper had been laid, either. The Americans soon sent B29 bombers to destroy the railway and he was despatched back up the line as part of a bridge-repair party.

Then word came of an atomic bomb and that the war in the Far East was over. Not that it caused much cheer among the men. They knew Emperor Hirohito had decreed that all prisoners would be killed if Japan surrendered.

But in yet another extraordinary twist of fate, Mr Stead says he woke up one morning and discovered the guards had fled.

After a two-day hike through the jungle, he and his fellow POWs were finally free and in the safety of an American army camp.

“It was like going to heaven; there was food and clothes, so we took off our rags and they gave us uniforms to wear.

“I remember yawning continuously for 48 hours, because I was so exhausted, both physically and mentally.”

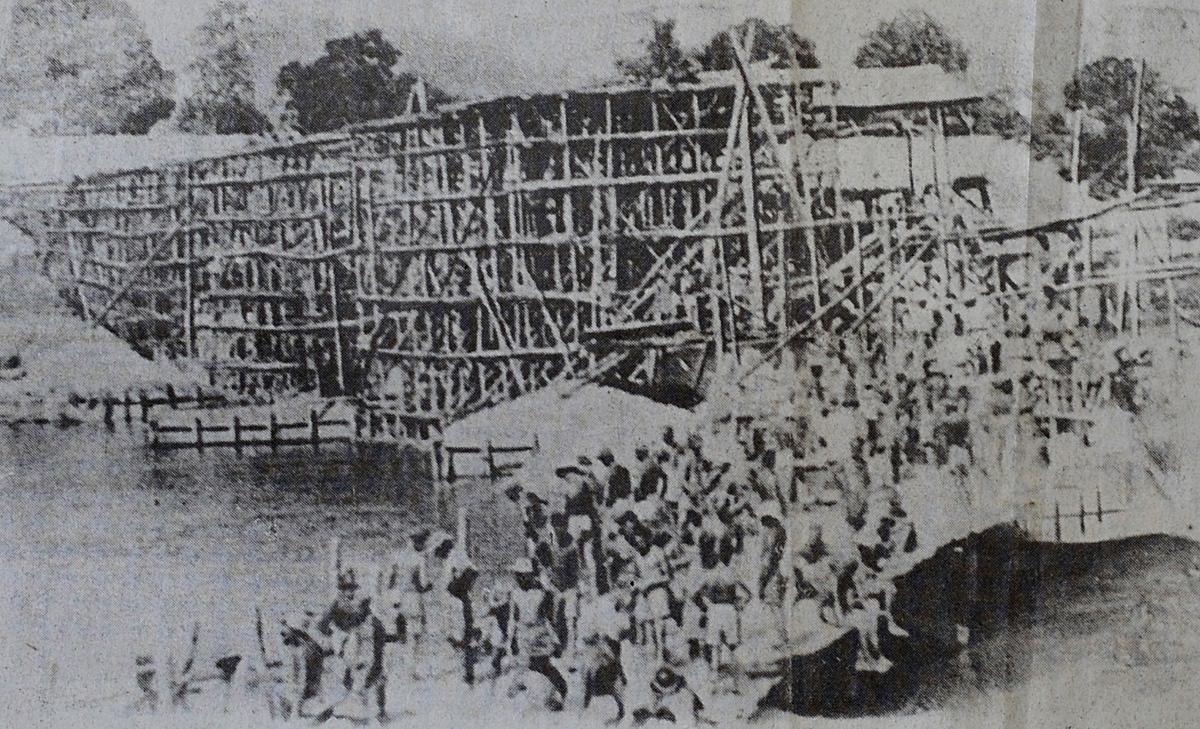

Mr Stead has never before spoken about his time on the Death Railway, where more than 16,000 POWs and 90,000 Asian labourers died while building the 258-mile track.

But, 70 years on, it is humbling to hear him say that his feelings towards the Japanese are ‘entirely neutral’.

“It was war; you either kill or be killed, simple as that. I might have personal grudges, but I think it’s illogical to condemn a nation because of a handful of people.

“We all tried in our own way to stay alive and some were more fortunate than others.

“I just happen to be one of them.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here