An exhibition at the University of York tells of the great lost library of Alcuin – one of the treasures of Anglo-Saxon England which vanished without trace. Or did it? STEPHEN LEWIS reports.

A STUNNING modern stained glass window in The Guildhall – designed after the Second World War by HW Harvey – depicts the history of York. One of the panels shows a medieval priest in brown robes delivering a lecture to a group of young scholars.

That ‘priest’ is Alcuin, one of the very greatest in a long line of great men and women York can claim as its own.

Alcuin was one of the pre-eminent scholars of his age, renowned across Europe as the “most learned man” of his time.

So famous was he that, in his 40s, he was persuaded by Charlemagne, the great King of the Franks, to join him at his court in Aachen as his teacher and chief adviser.

Before Alcuin left York in 782AD, he built up the library left to him by his own teacher, Archbishop Aelbehrt of York, into one of the greatest libraries anywhere in early medieval Europe.

Alcuin scholar Mary Garrison believes there could have been 100 or more books in that library. It doesn’t sound many by today’s standards, but this was the mid eighth century AD, when European civilisation was just beginning to recover from the Dark Ages.

Every book in Alcuin’s library had been written out by hand, on prepared animal skins, by scribes using quill pens and ink made from oak gall.

We know from Alcuin’s own writings that his library contained works by Aristotle and Pliny, Cicero and Bede, Vergil and St Augustine. The wisdom of the ages, distilled in a beautiful style of calligraphy known as Caroline minuscule.

That library, and the school Alcuin headed, ensured that in the mid 800s AD, York was one of the greatest centres of learning in Europe. Scholars came from far and wide to study with Alcuin, says Dr Garrison, a historian at the University of York.

The subjects he taught went far beyond what was typical at other great centres of religious learning.

Alcuin was interested in everything – mathematics, logic and geography; the movements of the stars and the planets; the ‘tremors of the earth and sea, the natures of men and cattle, of birds and wild beasts.’ He was a scientist and natural historian who saw learning of all kinds as the best way of celebrating God, says Dr Garrison.

In 782AD, when he went to join Charlemagne in Aachen, he left at least some of his library in York. Less than 100 years later, the great library had vanished utterly.

So what had happened? In short, we do not know. It may have been destroyed when the Vikings arrived in 866. The sacking of Lindisfarne by Vikings in 793AD had already shocked Europe.

Today, the Vikings are seen as a proud part of York’s history. “But when they first came they were destructive and terrifying,” Dr Garrison says.

Another possibility is that the books in the library were carried across Europe before the Vikings arrived. Alcuin may have taken some with him; other scholars, too, may have removed books to set up their own centres of learning.

Dr Garrison tells a story about a Frisian – or Dutchman – known as Liudger, who came to study in York with Alcuin in the 760s and 770s.

In 771 he had to flee York after a fight broke out between other Frisians and locals. Alcuin gave him books to take with him.

Thirty years later, Liudger founded the monastery of Werden. There, in the 16th century, account books were rebound with pages cut from early medieval manuscripts. Some of those manuscripts may have been from Northumbria in the eighth century – and possibly from Alcuin’s lost library.

Dr Garrison likes to think so, because it would suggest books from Alcuin’s library were used and treasured across Europe long after the Vikings brought fire and destruction to York.

The great library vanished, she says. “But the surviving information about its growth, use and disappearance makes a fascinating story.”

The story is told in a new exhibition, featuring Dr Garrison’s research, at the University of York all this week.

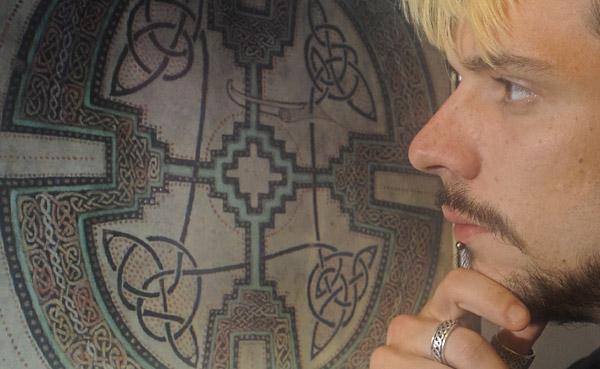

The Great Lost Library of Alcuin’s York uses photographs of surviving Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, alongside works by local calligraphers written in the Caroline minuscule script Alcuin promoted, to show what the library might have been like.

There is also a 3-D audio-visual display that brings the world of Alcuin to life.

It is a chance to find out more about an almost forgotten chapter in York’s history.

• The Great Lost Library of Alcuin’s York runs daily from 10am to 5.30pm until June 11 at the Sir Ron Cooke Hub at the University of York.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here