One of the few surviving veterans of the Far East campaign in the Second World War lives in Selby. For most of his life he has felt unable to tell his story, but this year is the 70th anniversary of the fall of Singapore and he agreed to speak to MATT CLARK.

UPHOLSTERING was an all right sort of job, but Maurice Crowther was 18, full of bravado, and anxious to do his bit for King and country. Excited at the prospect of seeing some action, Mr Crowther volunteered to join the Territorial Army.

One weekend he was at camp in Bridlington when the Second World War broke out. The East Coast was to prove his last sight of England for many years.

Mr Crowther was sent to Singapore. There was the huge naval base there, known as Gibraltar of the Far East, and his job was to man the guns that defended it.

At first it was a dream posting: plenty of sport, the occasional night out when he could afford it, but nothing would prepare him for the appalling conditions he was about to endure.

Singapore had been built to withstand a siege by sea, but when the Japanese destroyed allied fighters at the nearby airfield – before even they had even been unpacked – it left the city a sitting target for air attack. By 1942, Japanese bombs were raining down almost daily.

“It was horrible with no planes to protect us, for the civilians especially,” says Mr Crowther. “The air raids were worst, but you couldn’t bother about it and once we had to man the guns for 48 hours.

“If we had planes it might have been different, Churchill himself said ‘Singapore shall not fall’ and it wouldn’t have done by sea.”

On the night of February 8, Japanese forces landed under cover of darkness on the north-west coast. By dawn, they had two divisions established and the following day took Tengah Airfield.

Less than a week later Lieutenant General Percival, the general officer commanding Malaya, cabled for permission to surrender, hoping to avoid further destruction and carnage.

Two days later General Yamashita Tomoyuki accepted Percival’s unconditional surrender.

“They came by pushbike out of the jungle. We couldn’t have retreated any more or we’d have been in the sea. We were marched to Changi village from our station in the naval base, but I don’t think they knew how to deal with us really.”

With Singapore fallen, Mr Crowther was taken prisoner and sent first to Korea, then down the coal mines near Nagasaki.

“You’d come off night duty and just as you laid on your bed they’d come round prodding you with a bamboo stick just to taunt us.”

Even the coal face was deadly; guards had no idea of propping the pit, but luckily one or two of the prisoners had been miners and showed them how to do it.

Then there were the women, forced to strip to the waist and work the seam alongside the men.

“It was terrible to see. But you couldn’t think much about it really, you were too busy looking out for yourself. It was even worse than being in the siege.”

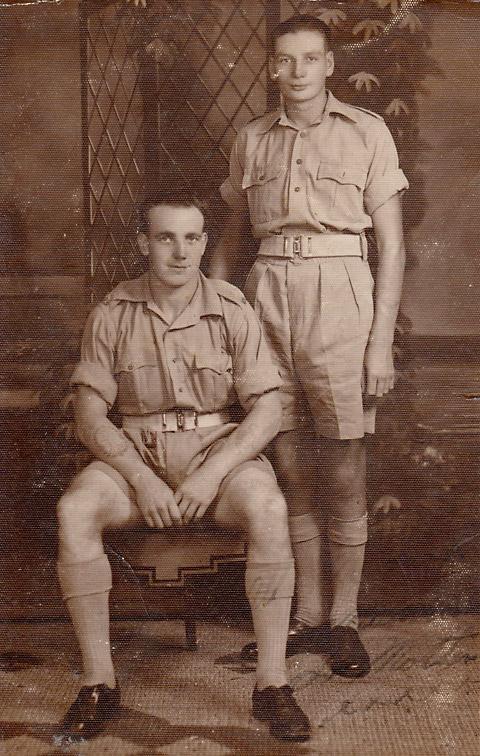

Mr Crowther, who is now 91, served with 122 Royal Artillery, the forgotten regiment, he calls it. For him it is important that the comrades with whom he served are anything but forgotten, especially his life-long best friend, Norman Wood, who died working in appalling conditions at the bridge on the River Kwai.

Mr Crowther could have suffered the same fate, but says he was ‘fortunate’ to contract dysentery and malaria. He was in a hospital bed while his comrades were taken away by ship.

“Norman and I played cricket as lads and we were on the same gun together in Singapore. Then he was shipped off to Burma. It was the last time I saw him and I was devastated.”

It was not until well after the war that Mr Crowther discovered the full gravity of the conditions at Kwai. Fortunately, he was recently able to return to Singapore thanks to the Lottery Fund’s heroes return scheme.

He also visited the cemetery of his fallen friends near Bangkok where he laid a wreath in honour of them.

“Norman’s grave wasn’t what I expected, just a little stone. I was with him for a while and I told him, ‘You will never be forgotten; just remember the good times, that’s what I do’.”

Mr Crowther says the Singapore he revisited was completely unrecognisable. “It wasn’t the same at all, a completely new city. But I thought of the Friday nights when we used to go out and I had a pint for Norman. They still sell the same beer, you know, and I thought, ‘I really wish he was here’.”

Mr Crowther never dreamed of going back to the Far East. The price was too steep and then there was the long plane ride to contend with.

“I didn’t think about it until this lottery job came on. I was treated so well and it was something I felt I had to do. It helped a lot to see Norman’s grave.”

There was a chance to go on an earlier trip but that fell through because of floods in Thailand. That, he says, is a shame because he would have got to see Kwai, where so many of his pals had died.

Mr Crowther also had another wartime escape, because he was working at the mine the day Nagasaki was attacked with an atomic bomb.

“They were bombing all day long, such a noise. But we didn’t know an atom bomb had been dropped. When we were released by the Americans everything we saw on the train for over an hour had been flattened.

“I remember feeling sorry, that day because they had been treated as badly as we were.”

One way Mr Crowther got his own back at the mine was by teaching a Japanese sentry how to box.

“He used to come for lessons every day and I’d give him a good punch each time. I don’t think he had a lot of sense really.”

Mr Crowther was sent to the Far East by a twist of fate. Had he been born a couple of months earlier he would have been too junior to go. Being so young at the time now leaves him as one of few surviving veterans of the conflict.

After all he saw and the ignominy of suffering at the hands of cruel captors, you could forgive him harbouring deep resentment. But not a bit of it; he believes both sides have much to answer for.

Indeed little of what he tells me is acerbic.

“My daughter says I never talk about it, maybe it’s too difficult, but I don’t regret going to Singapore. I had a great time and it was a good station before the fighting.

“I just regret losing so many good friends.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel