It is the size of a tennis court and will take years to restore. MATT CLARK meets some of the conservators working on York Minster’s Great East Window.

EVERY morning for six centuries, dawn sunlight flooded through the golds, greens, purples and scarlets in the Great East Window at York Minster. But four years ago, old age took its toll on the stonework holding the window in place and it had to be taken down to allow for remedial work.

Fortunately, that also presented glaziers with an opportunity to restore the panes and remove pieces of metal, used over the years to repair cracks.

For now, a life-sized photo of the window stands as a reminder because it will be a while before most of us see it again.

Not Rachel Thomas, though. She gets to look at the window almost every day in her work as a conservator painstakingly helping to bring back to glory what has been called the “Sistine Chapel of the stained glass world”.

Restoring each panel takes 600 hours and that, says Rachel, makes for an intimate relationship.

“It’s a very personal thing because when you spend that long you get to know each and every piece. No one else in the team will know it that well; you’re the only one who really understands how it all fits together.”

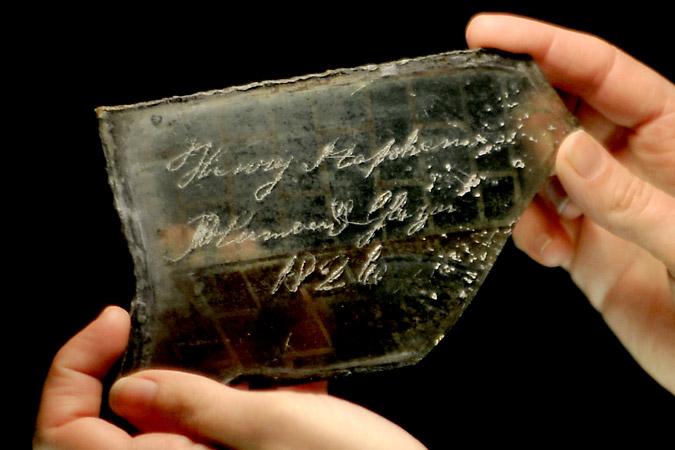

And the only one to discover all its oddities, such as the graffiti left by plumbers and glaziers. Rachel’s favourite is from 1826 which says simply, “Stephenson and son, aged 14”. It’s a tradition the glaziers continue by leaving tiny signatures in the glass paint.

Rachel is a member of York Glaziers Trust. It’s the largest team of specialist stained glass conservators in Britain and with good reason. York has more medieval stained glass than any other city in the country and the Minster has more of it than any other building.

Amid all that glory, the Great East Window is the undisputed jewel in its crown and at the size of a tennis court, the largest surviving expanse of medieval glass in the world.

This makes restoring John Thornton’s masterpiece of 1405-8 one of the most ambitious conservation projects in Europe.

Copies of Thornton’s contract survive, showing he was paid £56 for completing the window “on time and to the Dean and Chapter’s satisfaction”.

Today, that amount would not buy a single pane.

There is a degree of detective work involved because restoration has been carried out in the past, especially after the great fire of 1829, and spotting original from replacement glass is not quite as easy as you may think.

“It’s taken us a while to get our eye in, but you do get a feel for Thornton’s glass,” says Rachel. “There’s a particular quality about it, a scalloped shell edge or the way it’s fired. And the detail is striking. Some of it you would think was painted yesterday.”

Anna Milsom is working on row seven. The panels depict scenes both extraordinary and horrific, from a red dragon attempting to eat a woman’s unborn child, to more serene images of elders worshipping god.

For Anna though the true glory lies in the glass.

“It’s undulated with different thicknesses and very lively within the body of the glass where you can see all the bubbles and striations,” says Anna. “Antique glass holds the light better, unlike modern machine made glass which is very flat.”

Restoring the Great East Window is not only about conserving an object, there is the craftsmanship employed when the window was made, and indeed when it was restored.

While 1950s glass may have been flat and of poorer quality, it’s part of the window’s history and any temptation to replace it must be tempered.

“The original cutting was so precise, when you get complete glass side by side, they click together, it’s like a jigsaw puzzle, literally,” says Rachel. “If we can identify the original glass and get that cut line back together, we are left with the infill and other glass inserted over the last few centuries.”

Then comes the difficult job; deciding what to do with that infill. If it’s too bright, the wrong colour, or it detracts from the main panel it goes, if not it stays.

All the panels are photographed before work begins and rubbings made of the lead. Then they are dismantled so the glass can be examined. Once the jigsaw puzzle is put back together again, a drawing called a cut-line is made and the pieces placed on it. This is the design the glazier works to and is as close as possible to the original.

Nancy Georgi says getting up close to one panel for 600 hours reveals striking detail you would never see from a distance.

“We’ve found a few thumbprints and you can see angry faces, happy faces, even little buttons. I’m fascinated how the medieval glass painter has cut the glass. It is so precise sometimes we wouldn’t be able to do it with a modern glass cutter. It’s just perfect.”

A fine example is panel 11h, ‘God in Majesty’. Before and after pictures show the extent of previous lead repairs and the astonishing restoration work, including God’s mantle which had been patched with disjointed fragments over the years and is now back to its original purple splendour as described by James Torre’s 17th-century account of the panel.

The East Window glaziers follow two schools of thought on restoration.

The first is to insert slivers of lead into the cracked pieces of glass to retain the original piece, rather than replacing it with a good match.

The second is to take advantage of technology, by using conservation glues and paint which allow the original design to remain unhindered, but this method doesn’t work when bonding new glass with old.

The window narrowly avoided damage from another fire in the Minster stoneyard in 2009. Nine months later, fortune shone again as almost £10 million in Lottery cash was awarded to help not only the restoration work, but to convert the nearby 13th century chapel of the College of Vicars Choral into the window’s own studio.

In there Rachel says she sometimes feel as though Thornton is standing at her shoulder shouting, “No it should be done like that”.

“I wonder what he would have thought to us tinkering with his window 600 years on. It’s quite humbling really, now the glass could go on for another 300 years and our slot in its history is a very small period of time.

“It does put you and your life into perspective.”

• You can take a ‘behind the scenes’ glimpse of conservators at work in Bedern Glaziers’ Studio during regular guided tours, which cost £7.50 and can be booked through the Minster box office on 0844 9390015. To follow the progress of the restoration of the window, visit the newly constructed website yorkglazierstrust.org

Great East Window

The Great East Window is an Apocalypse window, which follows the theme of “I am the beginning and the end”. In its apex is God the Father holding a book stating, “Ego sum alpha et omega” (“I am the alpha and omega”, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, which was the language of the New Testament).

Top panels depict episodes from the creation of the world as described in the book of Genesis, to the events that will presage the end of the world and the second coming of Christ as told in the visionary Book of Revelation, known in the Middle Ages as the Apocalypse.

The bottom nine panels illustrate historical and legendary figures, including kings and saints, as well as donors who gave money for the work.

• York Glaziers’ Trust grew out of the Minster’s glaziers’ shop after the Second World War. Now it’s acclaimed as one the leading centres of conservation in Europe and is renowned for its work in York Minster, churches and historic buildings throughout Britain.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel