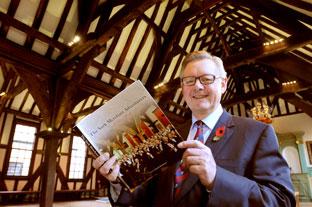

A sumptuous new book tells the fascinating story of York’s merchant adventurers and their hall. STEPHEN LEWIS reports

SOME time in 1356 three “citizens and merchants of York” – John Freboys, John Crome and Robert Smeton – spat on their palms and shook hands to seal a deal with landowner Sir William Percy.

The deal granted them “all that piece of ground with the buildings… in Fossgate” on which to build a hall that would serve as home to a “guild for men and women in honour of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary”.

So began the merchants’ guild which was to become known later as the Mystery of Mercers, and – from 1581 – as the Company of Merchant Adventurers of York. And here started the history of the magnificent hall which, today, is probably one of the finest surviving medieval guildhalls of its kind anywhere in the world.

In some ways, the spot chosen to build the new hall wasn’t ideal.

“The site was prone to flooding, and Percy may indeed have been glad to get rid of it,” says a sumptuous new book, The York Merchant Adventurers And Their Hall. But there was already a stone building there, with a chapel. And the location, next to Foss Bridge in the heart of York’s mercantile district, made it ideal for the merchants’ purposes.

Once the land was acquired, John Freboys and 12 other men applied to King Edward III for a formal licence to found their guild. The early members were a mixed group of businessmen and traders: a hosier, a potter, a tanner, a draper, a dyer and a spicer among them. But they clearly had the energy and drive of the true entrepreneur. Work on the hall that was to house their guild began quickly.

Impressive as the hall is today, it is easy to underestimate just how significant it was in the life of York 650 years ago. Other than cathedrals such as the Minster, and a few major castles, it “would have been one of the largest structures in the north of England”, says Paul Shepherd, who was Governor of the Company of Merchant Adventurers in 2010 when the new book was commissioned.

But this was no castle built by a baron or a king. It was a meeting hall owned and built by ordinary tradesmen and merchants. And it encapsulated the thrusting, entrepreneurial spirit of a city which, in England in 1356, was still second only to London.

York in the 14th century was the religious, administrative, social and economic centre of the north – largely thanks to its geography. It was at the confluence of two rivers, one of which, the Ouse, was readily navigable by sea-going ships of the day, which came here from Hull. York also had the only substantial crossing of the River Ouse – Ouse Bridge – for some distance around. The city was thriving.

“Sacks of wool and grain, bales of cloth, and fothers of lead were loaded onto the ships at the busy quays, while wine, wax, oil, salt, dyestuffs, glass, copper and the spices that were so important in cooking were unloaded,” records the book. “Ginger and cloves, cinnamon and saffron, pepper and oranges all found their way from Africa, India and the Spice Islands to the staiths at York.”

The city was also in the grip of an economic boom for another reason: the Black Death.

Just a few years before John Freboys and his colleagues shook hands with Sir William Percy, the bubonic plague had swept through Europe and then England. It brought devastation in its wake.

Millions died – up to 40 per cent of the population of England, some estimates suggest. In the changed, depopulated England that was left behind, wages and prices soared – and business boomed.

York, notes the book, saw a period of economic expansion after the Black Death. It is no coincidence, says Stephen Upright, the Clerk to the Company of Merchant Adventurers, that the origins of the organisation date to just a few years later.

No coincidence either that, in keeping with the spirit of the times – and with the sense that God had visited his anger upon the world – that original “guild for men and women in honour of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary” was more than just a banding together of self-interested merchants.

It also had both a religious function, and a charitable function. By 1371, the guild had applied for a licence to found a hospital in the undercroft of its hall. Initially, the aim was to offer care to 13 ‘poor and feeble’ people, but as more funds became available, more places were offered.

The guild – later Mystery of Mercers and ultimately Company of Merchant Adventurers – came to play a wider part in the life of the city as well. It had the power to grant licences to trade within York and appointed apprentices to trades. “We made sure that the apprentices behaved themselves, and that they would get a proper training,” says Mr Shepherd.

It even had a regulatory function. By 1588, for example, when a series of standard weights were issued by the government of Queen Elizabeth I, the Company of Merchant Adventurers had a set of bell-weights and scales it could use to make sure no traders were short-changing their customers. “If they persisted, they could have their licence to trade removed,” says Mr Shepherd.

Above all, however, this really was a company of merchants who were adventurers – men who staked everything on dangerous trade across the North Sea. The profits could be considerable, but so could the risks – sea crossings were notoriously unpredictable, Mr Shepherd says.

“These were real adventurers, in the sense that they were venturing capital. They were true entrepreneurs of their times.”

The York Merchant Adventurers And Their Hall is a serious but sumptuously illustrated history that also acts as a marvellous guide to the hall, its archives, and its collection of wonderful artworks. It tells the story of these ‘true entrepreneurs’ from that first spit-in-the-palm handshake to the role of the Company of Merchant Adventurers today.

It is a role that involves not only preserving the magnificent hall that bears their name, but also continuing the charitable works that have always been a part of the company’s tradition, from the days of the medieval hospital.

This year, for example, the company helped sponsor a number of York state school teams to take part in the Young Enterprise Company Programme – a national scheme whereby teenagers aged 15 to 19 set up and run their own companies for a year.

It’s hard to imagine anything more true to the spirit of the city’s merchant adventurers.

• The York Merchant Adventurers And Their Hall, edited by Pamela Hartshorne, with contributions by a working group of members of the Company of Merchant Adventurers, is published by Third Millennium, priced £20 softback, £40 hardback. It is available from the Merchant Adventurers Hall in York

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here