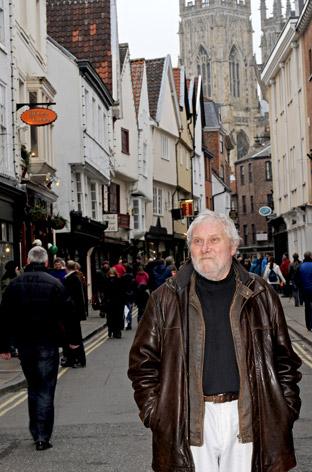

The New City Beautiful report sets out a vision for York 30 years from now. In the first of a series, STEPHEN LEWIS joined report author Alan Simpson for a walk along his proposed ‘Great Street’.

ALAN Simpson stands on Foss Bridge and stares down at the blank wall of the Blue Bicycle restaurant and the water lapping below.

“It’s trapped water,” he says, waving his arms in frustration. “Nobody can get to it.”

If this were Venice, he says, they’d have made something of this lovely bridge. There would be steps down to the water, and a footpath running alongside the river. Instead, York has turned its back on the Foss. The view from this bridge is uninspiring, the waters of the Foss dank and neglected.

Prof Simpson peers through the bridge’s balustrades to a small seating area further along, where a single solitary figure sits beneath what looks like a weeping willow. It would make a lovely public space, he says, if only people knew how to get there.

The professor is the urban design expert whose team, at the behest of Yorkshire Forward and City of York Council, has drawn up a 30-year vision for York’s future.

Officially unveiled at a public meeting at the Theatre Royal this week, the report, York New City Beautiful, takes a radical look at how, with the right will, vision and private and public investment, York could be changed for the better over the next 30 years.

There are a number of key proposals. Prof Simpson envisages a York city centre 30 years from now that’s virtually car free. There would be three urban parks in the centre; a fourth, based on the city walls, that would connect them; and a ring of six country parks on the outer ring road that would double as beauty spots and park and ride sites.

The report also suggests making much more of the city’s two rivers, instead of turning its back on them. And, perhaps most controversial of all, it suggests creating a Great Street running through the heart of York.

Starting at the University of York, this would run along Hull Road, through Walmgate Bar, up Walmgate, Fossgate, Colliergate and Petergate to Duncombe Place, and then turn west along Museum Street and Station Road to York Railway Station.

There are two things any great city needs, Prof Simpson says: a great river and a great street. York has the former, but turns its back on it. It doesn’t really have the latter. It’s time it did.

There have been many misunderstandings about his proposed Great Street, the professor admits. But it is important that people understand what he is talking about – because York people are being asked to comment on his ideas, and ultimately what we have to say will help determine which elements of his report feed into the city’s Local Development Framework, which will help shape the way York develops in future.

That is why he has joined me on a cold, grey February day: so that we can drive and walk the length of his Great Street and he can explain what it is all about.

First of all, he stresses, it will not involve widening or substantially changing any of the fine old streets along which it runs, and certainly not knocking down any buildings.

It will be about making the most of the streets we already have: getting rid of cars on parts of the route; lighting the streets properly; creating seating areas and public squares where people want to sit and meet and linger over a coffee; linking the several streets that make up the Great Street by paving them with an appropriate coloured stone or brick; and, especially on the roads outside the walls, planting avenues of trees along each side.

He’d also like to see the entire route used for a local transport system, preferably a tram running on rails set into the road’s surface.

It’s an ambitious idea. But how would it work?

We begin at the university, on University Road. Somewhere about here, he says, his Great Street would start, with a main entrance off it leading into the university itself.

We drive down University Road to Hull Road and head towards the city centre.

York has so few trees, Prof Simpson says, and it is a problem. “There is lots of traffic, heavy pollution, and not enough trees. That makes for an extremely unhealthy environment.”

He envisages the Hull Road section of the Great Road as a tree-lined boulevard – with an avenue of trees along each side and a central reservation in the middle.

Cars would be allowed here, but would probably be limited to 20mph. The pavements would be much wider than at present – twice as wide at least, he says – to create space for the trees, and for seats.

The road would be paved in accordance with a colour theme – possibly reddish – that would be picked up all the way along the Great Road. And, perhaps most importantly, there would be a tramline on each side of the road, the rails sunk into the surface.

We reach Walmgate Bar. It is wide enough to take a light tram, he insists, as we pass by and head up Walmgate, parking in The Press car park before continuing on foot.

Walmgate would be the next section of the Great Street. At the moment, Prof Simpson says, it is “brutal”, with not a tree in sight, the roads narrow and crowded, the street often filled with cars.

Again, his proposals would allow cars here, but limited to 20mph. The pavements would be wider, with seats. And there would be some trees on each side. He gestures at a row of flats and shops. “A few trees in front of that, and it would be a different place,” he says.

From the beginning of Fossgate, he envisions the street being closed to all cars apart from emergency vehicles.

The pavements could be widened, and the space between them filled to the same height with whatever surfacing has been chosen for the Great Road, he says: possibly red brick in a herringbone pattern, or even blacktop tarmac with red stone chippings.

The cars would be gone by now, but the tramlines would continue, over Foss Bridge and up to Whip-ma-whop-ma-gate. Without traffic here it could make a lovely piazza, he suggests, with tables and seats. It’s the same further up at King’s Square: a potentially lovely square ruined by the cars rushing along one side.

We head on up Petergate. There would be no more trees lining the street here, he concedes: it is too narrow for that. But without cars, the pavement could effectively cover the whole street, a bit like Stonegate; and there could be lots more places to sit and enjoy the street’s beauty. The tram lines could either stop here as we head into the narrowest part of the street, picking up again in Duncombe Place: or they could continue, as a single tramline only, right past St Michael le Belfrey. If that happened, tram journeys in either direction would be timed to take it in turns. “That is simple enough to do.”

And then we emerge at Duncombe Place. Prof Simpson looks up at the magnificent west front of York Minster, then down to take in Duncombe Place itself: at the lawns behind their little walls, the war memorial, and the clutter of road markings, signs, traffic lights and barriers.

“This should be the Trafalgar Square of York,” he says. “You’ve got the cathedral setting, the space, the war memorial. But it is all so divided up and cut across…”

Another missed opportunity, in other words.

That’s the thing about York, he says. It is a truly beautiful city. But, if we only made the most of what is already here, it could be so much more beautiful.

He hasn’t worked out all the details of his Great Street yet, he admits: it is just a vision. If it ever comes to pass, someone would need to decide how many trees were to be planted, and where; what material would be used to pave the road; where seats could be placed; how far the tram lines would go; where the cars would be stopped.

But that is all detail: the vision is what he hopes will inspire people.

And how would it all be funded?

Initially by using existing city council highways, public spaces and other budgets, he says. An awful loft of money is spent by the council on such things every year: not always as effectively as it could be.

If the council were working towards a long-term vision such as this, that money could be better spent.

And once businesses saw what was happening, they would want to start to get involved as well, he believes.

We’re not talking about something that will happen overnight, he says. “But when you have a vision, that’s when you capture the imagination. And from there it’s step-by-step steady progress.”

• To find out more about York New City Beautiful, and to make your own comments on it, go to york.gov.uk/consultation or phone community planning on 01904 551694 or 551673.

Fact file

Alan Simpson divided his childhood between Devon and Yorkshire. He went to school in Castleford and Leeds, and his father kept a boat at Naburn docks. He fell in love with York as a young man, he says, and regularly met up with friends here.

He and a group of friends continue to meet at the same time every year in the Blue Bell in Fossgate. Having a hand in a report which sets out a possible future for a city he loves is, he says, a real privilege.

As an architect and urban design expert, he has worked in the United States and the UK. A former Fitz-Gibbon Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, he was most recently Professor of Urbanism at the Mackintosh School of Architecture at the University of Glasgow.

He now works with UDA+UDS Urban Design, based in London and Newcastle upon Tyne.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel