IT was a moment of violence and savagery that has been shrouded in the mists of time.

Roughly 2,500 years ago, about where the University of York’s new campus is taking shape at Heslington East, a man in his early middle age suffered a sudden and ugly death.

He was hanged, then decapitated, his skull separated from his body. The skull was quickly buried in a small pit. There may well have been an element of ritual to the killing.

Fast forward 2,500 years. In 2008, archaeologists were excavating the area ready for the new campus to be built. They had found evidence of an extensive prehistoric farming landscape of fields, trackways and circular huts, dating back to at least 300 BC. And then, lying on its own in a muddy pit, they found a human skull.

It wasn’t the only time they were to find human remains on the site. Subsequent excavations were to reveal further remains, thought to date from the Roman period.

But when archaeologists got this particular skull back to the lab to clean it, they discovered something remarkable.

Rachel Cubitt, finds officer with the York Archaeological Trust, was cleaning soil off the skull’s outer surface when she felt something move inside.

At first she thought it might just be mud or soil. But peering through the base of the skull, she spotted un unusual yellow substance inside.

It was, she admits, a “bit unsettling”. And it jogged her memory about a university lecture on the rare survival of ancient brain tissue.

What she had found, in fact, was Britain’s oldest brain.

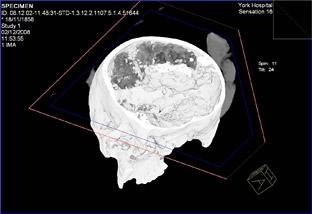

A CT scanner at York Hospital was used to produce startlingly clear images of the brain. And then Dr Sonia O’Connor, a research fellow in archaeological sciences at Bradford University, was brought in to examine the brain in more detail.

She has been studying it ever since: and tomorrow, she will talk about her discoveries in a public lecture for the Yorkshire Philosophical Society at the Tempest Anderson Hall in York.

Her talk, according to the society, will offer “powerful evidence of the final moments of this individual’s life, his death and burial.”

So what do we know about him? Not a great deal, admits Dr O’Connor. We know from radiocarbon dating that he died sometime between 763 and 415 BC: at least 2,400 years ago, in other words, and possibly earlier. He was a fully grown man, aged between 26 and 45: and probably not older than 36. “We can’t tell closer than that, because we have just the skull.”

His skull was probably buried very quickly – which may help explain why it survived, though the “anoxic” conditions of the waterlogged mud where it has lain for millennia were also responsible. And there may have been a ritual or sacrificial element to his death.

He was hanged first, and then his head cut off, quite neatly and precisely, leaving the skull and two vertebrae.

This was buried in a pit in an area archaeologists are starting to associate with ritual.

“There are a lot of very unusual pit fillings, which suggest this might have been some sort of ritual environment,” Dr O’Connor said.

They include the headless body of a deer; some antlers; and some pits with a single wooden stake in each.

“They could have been used to mark the pit.”

An Iron Age mystery to have you shivering in your beds.

• Dr Sonia O’Connor will be talking about York’s Iron Age brain at the Tempest Anderson Hall at 7.30pm tomorrow.

Entry costs £3 on the door, and is free to members of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here