New parks, a car-free centre and a “Great Street” running through the heart of York form part of the city’s vision for the next 30 years.

The newly-unveiled master plan for how the city could evolve also includes a facelift for its riverside, linking up the missing stretches of the Bar Walls, creating more green space and rethinking the way the stalled York Central development and other projects could be designed.

A report on the blueprint for York’s future, aimed at playing a pivotal role in its Local Development Framework (LDF) and boosting its economy by enticing more investment, has been revealed by a team led by urban design expert Professor Alan Simpson.

It says its “constrained transport network, street clutter and lack of quality spaces” risk holding it back in the face of competition from rival cities.

The vision, under the banner New City Beautiful, has been drawn up through Yorkshire Forward funding and will ultimately go out for public consultation before the elements which could be contained within the LDF and the council’s City Centre Area Action Plan are decided.

Among its ideas are devoting the city centre to pedestrians, cyclists and public transport and creating a “Great Street” between the University of York and York Central, as well as park areas at the Museum Gardens, Foss Basin and Kings Pool and new riverside frontages and walkways.

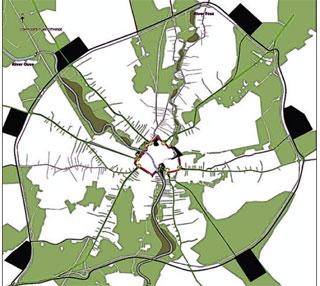

Tree-lined paths and open spaces would link the Bar Walls in an idea titled “Rampart Park”, while the city’s Park&Ride sites could also be revamped as country parks and its Strays being used to connect the outskirts of York with its centre.

Professor Simpson said: “A plan of this nature, scale, ambition and longevity can attract the interest of people looking to invest.

“There are people looking for these long-term city-making exercises to happen, as London has shown, and York is worthy of consideration at this level.

“Just because we are not building doesn’t mean we can’t plan, and this vision is about rediscovering York.”

York Civic Trust chairman Sir Ron Cooke said: “It provides the underpinning for economic growth and it is clear there are some very interesting ideas, including the quality of the public realm.”

And Coun Dave Taylor, the council’s heritage champion, said: “What makes this plan great is that it’s like York, only more so, and I’m delighted a visionary like Prof Simpson has said many of the things we have been saying for years.”

Adam Sinclair, chairman of York Business Forum, said: “We would support anything which enhances the quality of the city centre, which is the jewel in the crown of our economy.

“But any traffic issue needs to be handled with care in terms of traffic being drawn away from the centre to areas such as Monks Cross, and I hope that is understood.”

‘A giant park would boost York’s heart’

A PARK city. That’s the vision of York’s future set out in the most important master plan since the Esher report in the 1960s.

The New City Beautiful report produced by urban planning expert Prof Alan Simpson and his team envisages a city centre cleared of cars within 30 years. Instead, a series of new urban parks, connected by an expanded ‘Rampart Park’ based on the city walls and by a network of cycle paths and footstreets, will effectively turn the city centre into one giant urban park.

Running across it, using existing street plans, would be The Great Street – a tree-lined boulevard, possibly complete with tram route, connecting the University of York on the one side with the York Central site on the other.

The city’s two rivers would be put at the heart of the new-look York, the existing inner ring-road would be used mainly by public transport and pedestrians as cars were banished, and a series of new ‘gateways’ would be set up around the edges of urban York – country parks where people could leave their cars to come into the city centre.

The report, commissioned by Yorkshire Forward, sets out a possible 30-year framework for development of the city. It makes clear York is in many ways an attractive place to live. But with the right vision, the city could be so much better, it argues.

The problems holding York back are set out in pitiless clarity: congested streets and poor transport access; cluttered, disorderly streets; too few decent public parks and spaces; and a failure to make the most of the riverside. The city is also too fractured, with the University of York and the railway station in particular left isolated, the report says.

Between them, these problems are hampering the city’s growth, restricting the opportunities for inward investment, and preventing York from being even more beautiful and pleasant to live in than it is, Prof Simpson says. Many of the recommendations made to address these problems are startling.

Others may appear unrealistic, especially in the current economic climate. But the time-scale, Prof Simpson points out, is 30 years. These are not changes that would be expected to happen overnight Ultimately, it will be up to city councillors and the people of York to decide just how many of the recommendations we take on board. But one thing is for sure: no-one can accuse the Simpson report of lacking vision – an allegation too often levelled at York itself.

Here, we look at a few of the suggestions in more detail.

The Great Street

The New City Beautiful report proposes establishing a main route running right through the heart of York, connecting the university at the east to York Central at the west.

The street would adopt existing street plans, running along Hull Road, Walmgate, Fossgate and Petergate to the Minster, and then along Duncombe Place and Museum Street and across Lendal Bridge to the railway station.

The reduction in car numbers Prof Simpson sees as inevitable and necessary will leave room for grass verges and avenues of trees, for example along Hull Road, to create a boulevard effect, and give the entry into York from the east some of the quality of Tadcaster Road.

There could even be a tram route along the street, Prof Simpson said.

“The Great Street will unite the city’s great civic, cultural, natural and educational amenities,” says the report.

Focus on pedestrians

York as a city is “massively over-trafficked”, says Prof Simpson – by which he means it is dominated by the car in a way that is simply not sustainable.

That, inevitably, is going to change, he believes – possibly gradually, over a period of many years.

There are many factors that will help this process – shared bicycle schemes, shared car schemes, better public transport. But in 20 or 30 years time, he believes cars will have been virtually banished from the city centre, creating a city-wide pedestrian zone.

“In 20 years time, people will look back and say ‘look how funny they were, people used to drive everywhere!’” says Scott Adams, a director of Urban Design Skills which helped produce the report.

The riverside

The Ouse and the Foss are unique parts of York’s heritage, says Prof Simpson – but for too long, the city has turned its back on them.

The report envisages changing all that, by making the Ouse and the Foss key elements of the city centre – with new river frontages, open spaces and river walks.

It is partly about re-orienting riverside properties so they face the river – or have double fronts – say Prof Simpson and fellow report author Scott Adams of Urban Design Skills.

But it is also about the city’s mindset towards the river.

The report’s authors say they are well aware of the problems caused by multiple ownership of properties along the riverfronts.

Making better use of the riverside won’t happen overnight.

But it can start small – the City Screen boardwalk showed what a difference can be made.

And there are plenty of other “easy wins” to get the process started, Mr Adams says – such as connecting Museum Gardens to the riverfront.

City parks

The document envisages the creation of three new urban parks. One, the ‘civic park’, would be based around the Eye of York and would stretch down through St Georges Fields to the Blue Bridge at the confluence of the Ouse and Foss.

The second, the ‘cultural park’ would be an extension of Museum Gardens to link up with the river and land to the south of the river. The third, the ‘production park’, would be based around Foss Islands Road and the King’s Pool.

The parks would not be parks in the style of Rowntree Park as we have it today. They would include shops, businesses and even streets. But they would be much greener than the areas are now, with more trees planted, more public open space, more pedestrianisation. The three parks would be connected by a fourth, circular park – the ‘rampart park’, centred around the city walls.

“We would see these as not being distinct parks, but being connected in to what is effectively a city-wide park,” Prof Simpson said.

New outer gateways

The report envisions a ring of six new country parks around the outer ring road, some of them on the site of existing Park&Ride sites.

These would be linked to the city centre along parkways dominated by public transport.

The idea of the new country parks would be to combine park and rides with country parks that people actually want to visit, the report says.

“The idea is to encourage people to leave their vehicles in the country parks before entering the city and inviting greater use of public transport,” the report says.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel