WILLIAM Snawsell was an important man in 15th century York, even though the folk of the city had a lot to answer for when it came to the pronunciation of his surname.

A wealthy Stonegate goldsmith and city councillor, who served both as Sheriff of York and Lord Mayor, his family originally hailed from Snowshill, in Gloucestershire.

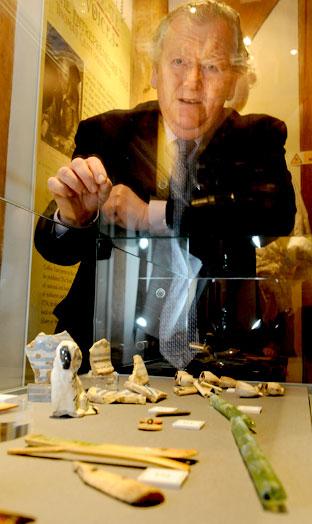

They brought the name with them when they moved up north. But Yorkshiremen had trouble pronouncing it, hence the corruption to Snawsell. “In fact, it often comes out as Snozzle,” says Dr Peter Addyman, of the York Archaeological Trust.

Snawsell’s father, another William, was also a goldsmith. The younger William, who was born in York in 1415, followed his father into the profession. As a young man, he had a shop built in Minster Gates, one of the most prestigious trading addresses in the city.

He married Joan Thweng, a woman of noble birth whose family had powerful connections, and by 1464 was Sheriff of York. And about this time, he moved into the property now known as Barley Hall.

The property backed off Stonegate – there would have been a commercial premises fronting on to the street, and then a long, narrow building behind used as living quarters.

Snawsell had really made it, because the Stonegate of the day was in many ways one of the premier streets in the whole country, Dr Addyman says.

“It was a very rich area: in the middle of the second city of England. It was the main street leading to the Minster. Everybody visiting York would go up it.”

Including, quite possibly at some stage, King Richard III, Dr Addyman says.

Barley Hall today has been restored so as to try to recreate what it would have looked like in Snawsell’s time, when he lived here with his wife and three children – son Seth and daughters Isobel and Alice.

Every detail has been based as closely as possible on the archaeological evidence – from the tiled floor in the great hall to the pottery on the tables, the tables themselves and the benches that line them.

It makes sense, therefore, for the Snawsell family to be the ‘starting point’ for Barley Hall’s latest exhibition, Stonegate Voices.

The exhibition is essentially a celebration of this ancient street of craftsmen, with the emphasis very much on the craftsmen themselves, and their families.

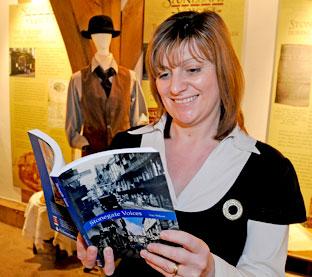

Those interested in York’s recent past might already be familiar with Van Wilson’s excellent oral history book, also called Stonegate Voices.

Published late last year, it is essentially a series of interviews – all transcribed into print by volunteers – that Van and her team conducted with York citizens who remember life in Stonegate and the surrounding streets between 50-100 years ago.

The book combines these interviews with old photos to great effect, providing a vivid and unparalleled glimpse into the recent history of the area.

One thing the book couldn’t do, of course, is let you hear the voices. Those with an MP3 or iPod and access to the internet can download many of the interviews as podcasts – so you literally will get to hear the voices of Stonegate.

And now, thanks to a new audio tour that forms part of the Stonegate Voices exhibition at Barley Hall, you will be able to hear some of them there, too.

It is fascinating to hear the authentic Yorkshire voices recalling life in the area 50 and 60 years ago, and even longer. But the Barley Hall exhibition goes way beyond the scope of the book, and the online podcasts.

It sets out to introduce us to the people who lived in the area right back to the time of William Snawsell. People such as printers John and Grace White who, in 1688, published the manifesto of William of Orange. After John’s death, Grace continued the business – and on February 23, 1719, produced the first York newspaper, the York Mercury.

There is bookseller John Hinxman who, in 1757, took over The Sign Of The Bible shop in Stonegate, and achieved success by publishing Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy.

More recently, there were craftsmen such as John Ward Knowles – the Victorian glass painter and stained glass artist, whose business was also at the shop known as The Sign Of The Bible – and the wireworker George Kilvington, who made everything from chandeliers to bird cages and even the wiring for bras.

The Barley Hall exhibition is fairly simple, taking up just two rooms, but fascinating nonetheless.

There are panels on these and other families who lived and traded in the street, together with two cases of artefacts dug up by archaeologists – everything from clay pipes and wooden Victorian toothbrushes to a medieval eight-lobed drinking cup.

There is authentic reproduction clothing from the time of the Snawsells; that audio tour; a ‘census’ game where you can type in your own personal details and find out which Stonegate resident from the 1901 census you most resemble; facsimiles of early York newspapers such as the Mercury and Courant; and, for the children, a chance to print their own newspaper, the Coffee Yard Times.

• The Stonegate Voices exhibition at Barley Hall officially opens on Wednesday, although much of it is already up and running. Admission to Barley Hall is £4.50 adults, £3 children. Family tickets are also available.

•To download podcasts of Stonegate residents recalling life in the street 50 or more years ago, visit the barley hall website barleyhall.org.uk • Van Wilson’s book Stonegate Voices, published by the York Archaeological Trust, is available, priced £9.99, from Barley Hall, Jorvik and local bookshops.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here