IT WAS hot and sultry the night the Minster burned. York had been in the grip of sweltering temperatures for so long that farmers were desperate for rain.

In the early hours of Monday, July 9, 1984, lightning flickered across the night sky was made all the more eerie by the lack of thunder. Then, at about 2.30am, a fire alarm shattered the silence around the deserted Minster. It automatically triggered an alarm at the Clifford Street fire station, where members of Red Watch were on duty.

Firefighters were regularly called out to false alarms at the great Gothic cathedral. It was only as they sped into Deangate 12 minutes later that the men of Red Watch realised that this time it was for real. The air was hazy with smoke, and flames could be seen on the Minster roof.

There was a detailed plan in place for what to do should the worst ever happen and the Minster catch fire.

After a moment’s shock, the men of Red Watch swung smoothly into action.

They quickly established that the fire was in the space between the South Transept roof and the ceiling below. Ladders were set up in the aisles in the galleries running down both sides of the South Transept. But burning wood and lumps of molten lead forced the firefighters to evacuate.

Urgent reinforcements were sent for, and a fire command unit set up. The fire was spreading towards the Minster tower from the gable end of the South Transept. Despite heroic efforts, it became clear firefighters could not save the South Transept roof. The great fear was that the fire would spread into the Nave or Central Tower. The decision was taken to try to collapse the South Transept roof to prevent that happening.

A powerful jet of water was aimed at the burning timber at the end furthest away from the Central Tower. It collapsed, bringing the rest of the South Transept roof down with a a roar. Timber smashed down on to the Minster floor, but the great building had been saved.

At 5.24am, with the first grey light of dawn spreading across the scene of devastation, firefighters were able to signal that the blaze was under control.

It was estimated that at times the fire had reached temperatures of 1,000C. Twelve of North Yorkshire’s 21 fire stations were mobilised, and 114 firefighters and ten officers were directly involved in battling the blaze.

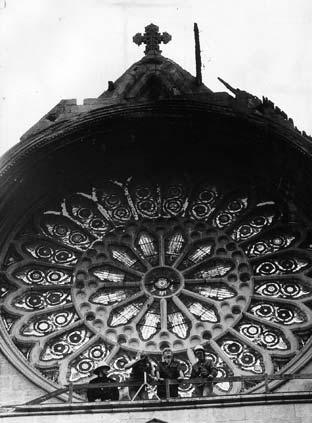

The damage was estimated at the time to run to more than £1 million. But as he stood in the wreckage and surveyed the scene, Peter Gibson of the York Glaziers Trust, who was soon to become internationally famous for saving the Rose Window, noticed that the cross above the South Transept gable was still standing. “It was badly cracked, but it was there,” he said. “It was a symbol. I knew that one day it (the Minster) would be all solid again.”

And so it proved. Just over four years later the Queen visited to inspect a Minster that had been restored to its full glory.

But without the heroic efforts of North Yorkshire’s firefighters that night, it could have been so much worse.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here