David Wilson relates what happened to York during the two world wars

THIS last year has brought the horrors of war to our TV screens and social media on a daily basis, and it looks as if both the Ukraine-Russia conflict and the Palestine-Israel war are likely to continue well into 2024.

While most of us in York may experience these wars at a distance, the oldest citizens of our city may well remember what it was like to live through at least one of these horrendous attacks on our island home from 1939-45.

Nowadays, The Great War of 1914-18 lives on in war memorials and family memories handed down through the generations.

Wars bring with them not just the loss of life and destruction of buildings but collateral damage to society and its way of life. Not least among such damage is the reinforcement of prejudice and discrimination.

In her book York in The Great War, Karyn Burnham recounts the instance of a Mr Joseph Foster Mandefield who ran a hosiery business in Monkgate. Some of his customers thought his name sounded German and he wrote a letter to the local press attempting to scotch this rumour by emphasising that his family had originated from France. But his letter had no effect and the slanderous accusations continued. Mandefield was unjustly accused of being an enemy alien and attempting to kill off half of York by poisoning the local reservoir.

Within the first few months of the Great War, all non-naturalised British residents were arrested and imprisoned in an internment camp along the Leeman Road.

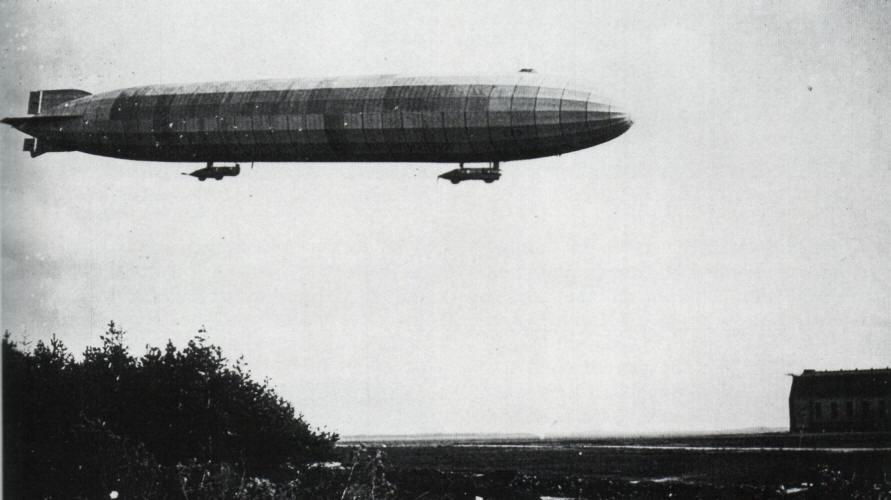

Blackouts in York were introduced in January 1915. All lights were to be switched off from before sunset until one hour before sunrise. The attacks on the city came later in the form of air raids by Zeppelins, rigid airship bombers.

Just before a Zeppelin raid, local residents were issued a warning by means of a police whistle or football rattle. Later, silent warnings were given by repeated raising and lowering of the gas pressure which caused lights to dim and brighten successively.

On the night of May 2, 1916, a Zeppelin dropped a bomb on Nunthorpe Avenue killing Emily Chapman, a local resident. Another Zeppelin dropped 18 bombs on Upper Price Street, Peaseholme Green and St Saviour’s Place killing nine people, injuring 40 and leaving a trail of destruction behind it. The third and final Zeppelin raid took place on November 27. The two Zepps came under such barrage of fire from anti-aircraft guns that they retreated, having dropped bombs on Haxby Road, Fountayne Street and Wigginton Road. Only one person was injured and nobody was killed.

It was only three years after the start of the Second World War that buildings in York were affected directly. The city lacked military targets of any significance except the railway and the airfield in what is now Clifton Moor.

But York, along with Canterbury, Norwich, Bath and Exeter were to come under Nazi bombardment in the Baedeker raids, so-called after the name of the German tourist guide books. The main attack was during the night of 28th/29th April 1942 and is thought to have taken place in retaliation for the RAF’s attack on Lübeck. In his book The Baedeker Blitz, Niall Rothnie describes in considerable detail the progress of the raid. Initially, incendiary bombs fell on Pickering Terrace, Bootham Terrace, Burton Stone Lane and Queen Anne’s Road.

Some 30-40 bombers actually hit the city damaging the railway station, The Bar Convent, and Garfield Terrace near the railway line. In the centre of York, incendiary bombs fell on top of the 500-year-old Guildhall, a Rowntree’s warehouse by the River Ouse and in the grounds of a nursing home 65 yards from York Minster.

Subsequent German records show that the Luftwaffe deliberately avoided bombing York Minster itself. Two or three bombs landed in Chatsworth Terrace and Amberley Street and these accounted for more than a quarter of those killed.

There was also bomb damage to several houses in Nunthorpe Grove and Nunthorpe Crescent but many of the residents there survived thanks to their Anderson or Morrison shelters. In addition to the private shelters, York had six public shelters in the city centre. The largest was in Lower Priory Street and was able to shelter 477 people. The smallest was in the public toilet in Parliament Street (now long since removed). There were a further 89 public shelters throughout the 13 wards of the city.

Altogether, 579 of the 27,000 houses in the city were left uninhabitable and 2,500 sustained damage. Statistics relating to those killed in the raids vary from between 76 and 82.

York emerged relatively lightly compared to Bath which suffered two raids and four times the casualties, but it is often maintained that The York Civil Defence Services were exemplary in their work to protect local people from injury and death.

One of the few publicly visible witnesses to the havoc wrought by the Second World War in York is the partially ruined church of St Martin-le-Grand in Coney Street, now converted into a Garden of Remembrance. But the painful effects of war always live on in the memories and lives of survivors and loved ones. “For your tomorrows, they gave their todays.”.

David Wilson is a community writer with The Press.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel