David Wilson highlights three places in the city which remind us of when our forebears fell ill or where they were treated

HUGE waiting lists for hospital treatment have been commonplace in recent years, especially during the pandemic, and such delays are certainly a scandal which needs to be urgently addressed. But we should also remember that for many of us in the 21st century, the effective treatment of illnesses is unprecedented in history.

For York residents living centuries ago, present-day medicine would have seemed little short of a miracle and the notion of free medical treatment would have been beyond the wildest dreams of most people.

You only have to arrive by train in York to be confronted by the ravages of historic disease in the city. Just opposite the train station, hidden by trees in a grass verge are the 20 gravestones erected to some of those who died in the cholera outbreak that affected the city for four months in 1832.

One of these gravestones made a big impression on me as it commemorates 75-year-old Anthony Chambers. He was a Hull resident who had the misfortune to die of cholera in this York epidemic on June 15, 1832. Was he separated from his family and friends at the time of his death, I wonder? And were they able to attend his funeral?

The epidemic was, of course, no respecter of age, and another gravestone commemorates Joseph Wolstenholme’s 16-year-old wife Mary who died the following month. In 1832 the population of York was 25,357 and the epidemic killed 185 of them.

A further 450 people fell ill but recovered. So, what was the cause? Victorians believed that it was the caused by the presence in the air of what was called miasma. Miasma was a poisonous vapour containing particle of foul-smelling decaying matter.

But thanks to the pioneering work of York-born early 19th-century Dr John Snow, medical specialists nowadays know that such cholera outbreaks occurred because of poor sanitation and eating food or drinking contaminated water. In fact, it wasn’t until 1895 that the city had an effective sewerage system. And in Victorian York, standards of hygiene left a lot to be desired, especially in the city’s slums.

Seebohm Rowntree’s ground-breaking social study of living conditions in York showed that nearly 28 per cent of the city’s population (more than 20,000) at the turn of the 20th century lived below what he referred to as the ‘poverty line’.

Walk on down Station Road towards the city centre, cross Lendal Bridge and you come to the Museum Gardens. The medieval building to the right of the entrance is the undercroft of what was once St Leonard’s Hospital Infirmary built between 1325 and 1350. It contains medieval as well as Roman stonework. If you access the ruins from inside the Museum Gardens you will notice its high vaulted ceilings thought to encourage fresh air and drive away the miasma that supposedly caused a whole range of fatal diseases including plague, smallpox, typhoid, dysentery and the sweating sickness.

There would also originally have been large windows which served a similar purpose. St Leonard’s replaced the earlier hospital of St Peter’s which was destroyed by fire in 1137 and was connected with the Minster.

Hospital care in the Middle Ages was somewhat different from today’s. The sick, the poor, the elderly, the infirm and even orphans were all given refuge in the hospital either until they died or could be discharged to carry on living and working in the city. Nurses, who were usually religious sisters and lay brothers, attended to their spiritual as well as tried to alleviate their physical afflictions. The regime was strict. It was a condition of any treatment that the patients should first confess their sins and then take part in regular prayers and religious services.

It is claimed that St Leonard’s Hospital was one of the largest in medieval northern England, that is until the 16th century. An unfortunate legacy of the Reformation was that the institution was closed down in the 1530s at Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. York was then left without a hospital for some 200 years until 1740 when the York County Hospital was established.

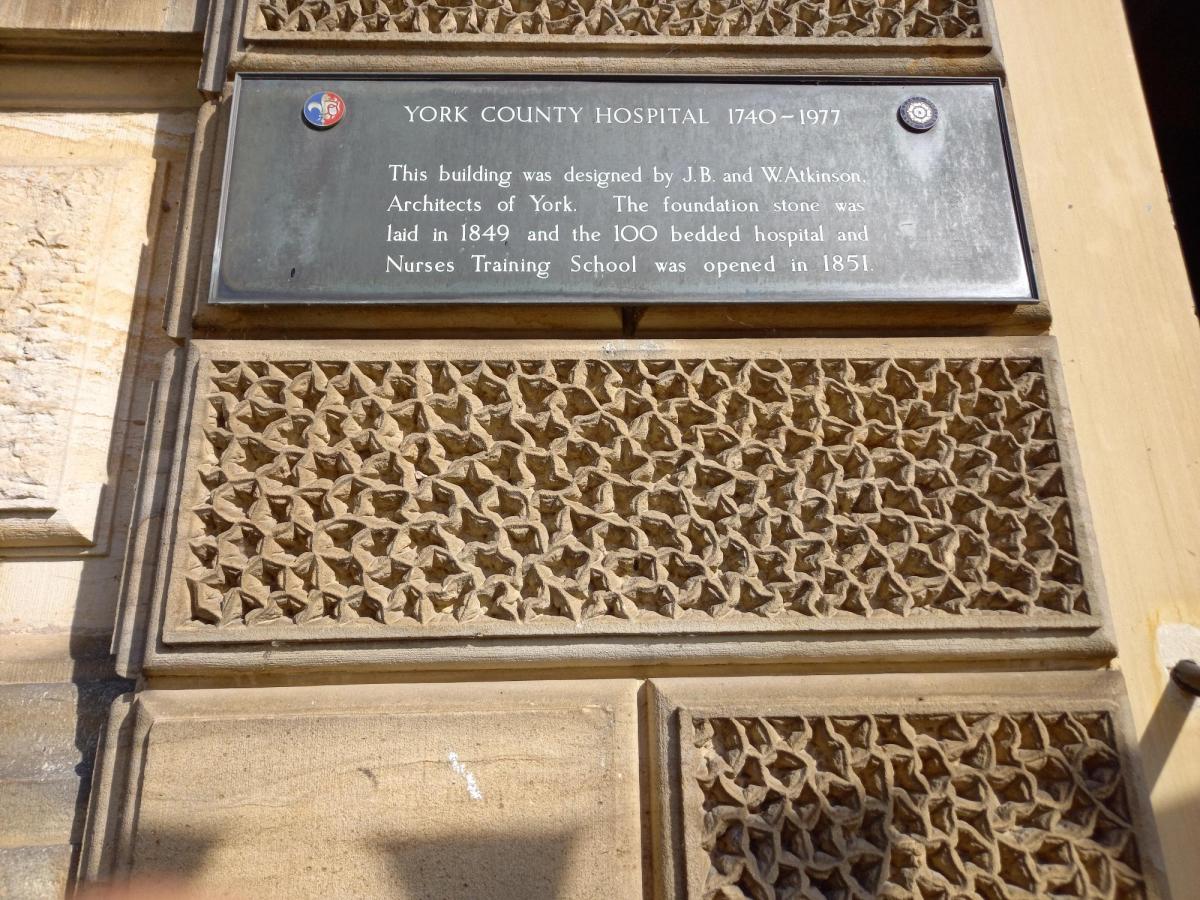

Walk on along Museum Street into Duncombe Place and past the Minster into Deangate, Goodramgate and on into Monkgate. On your right you will see an imposing brick building the rear of which looks out on to Sainsbury’s car park. This was the York County Hospital. Founded as what was called a voluntary hospital, York County Hospital was originally a charitable foundation supported by subscriptions of the wealthy to treat poor and deserving patients for free.

The original hospital building was replaced by a new building in 1851 with one hundred patient beds. In 1887 the hospital merged with the York Eye Institution and later, in 1905, a nurses’ home was added. During the flu epidemic of 1918-19 so many nurses were off sick at the same time that the hospital had to close for two months. Some present-day York residents may remember the York County Hospital as the place where severely injured casualties of the Luftwaffe’s Baedeker raids were treated during the Second World War.

In 1977, the hospital facilities moved to York Hospital. This Grade II building was re-named County House and for a while became the Head Office of Yorkshire Water. Finally, in 1998 permission was obtained to convert the building into a number of luxury apartments.

York is today a comparatively prosperous tourist and university city with an enviable record of healthcare. These three landmarks of semi-hidden history bear witness to the historic struggle of York people against the omnipresent ills of sickness and death.

David Wilson is a community writer for The Press

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel