David Wilson tells the story of the York-born founder of the ‘Bluestocking’ movement

A generation or two ago, intellectual women, especially those who weren’t married, were referred to somewhat disparagingly as ‘bluestockings’, a term which has fortunately more or less disappeared from everyday conversation today.

‘Bluestockings’ were women who had turned their backs on the conventional lifestyle of patriarchal society by not marrying or having children and had chosen instead to dedicate themselves to debate and discussion of public affairs.

No doubt the men and women who used this derogatory term felt challenged by intellectually capable women. But where did the word ‘bluestocking’ come from?

Walk down Minster Yard, past the wall outside the Treasurer’s House, and you’ll notice two or three York Civic Trust blue plaques that immortalise famous historical figures who have lived in the city.

One of them, erected only as recently as 2019, celebrates Elizabeth Montagu, founder member of the ‘Bluestocking’ movement, writer, and patron of the arts.

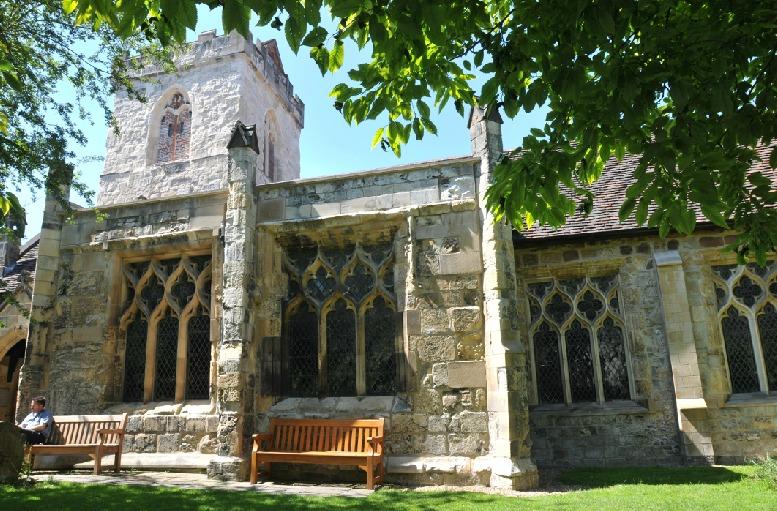

Elizabeth Montagu was born in the Treasurer’s House on 2 October 1718. Her father, Matthew Robinson, had become a tenant of the owner, Miss Jane Squire, and he and his wife went on to have nine surviving children. Elizabeth and her younger sister Sarah were both born in York and were baptised in the church of Holy Trinity, Goodramgate. Elizabeth in 1718 and Sarah in 1723. Elizabeth was married in 1742 at the age of 20 to a man 50 years older than herself, the MP Edward Montagu, wealthy proprietor of a coalmine and grandson of an earl. He died in 1775 leaving Elizabeth a wealthy woman who increased her inheritance by shrewd business investments in the rising price of coal. Edward and Elizabeth had several homes: a country estate at Sandleford Priory near Newbury and a prestigious London house in Mayfair.

It's difficult for us to step into the shoes of a society where even upper-class women received no formal education. But this had certainly been the case in previous centuries. Their role had been limited to the domestic sphere of activities such as needlework and music and women were seen as incapable of taking part in discussions about philosophy, science, and the arts.

Literary critic and writer Anna Barbauld had once expressed the view that ‘the best way for a woman to acquire knowledge is from conversation with a father, brother or friend’.

And Mary Astell, a 17th-century proto-feminist, had asked the question: ‘If all men are born free, how is it that all women are born slaves?’ However, from 1750 onwards, signs emerged of the very first stirrings of change in the social role of women.

In the mid-18th century together with her friend, Elizabeth Vesey, Montagu set up an informal social and educational movement in their London homes. Known initially as ‘breakfast clubs’ and modelled on the French salons, these gatherings marked a break with traditional, non-intellectual women’s activities. There were no formal membership fees and discussion of politics was prohibited as was card-playing and alcohol. Learned women along with invited male guests discussed issues around literature and the arts rather than fashion over tea and biscuits. Notable members of the bluestocking circle were religious writer and philanthropist Hannah More, satirical novelist Francis (Fanny) Burney, diarist and patron of the arts Hester Thrale, an important source of information about Dr Samuel Johnson, as well as actor David Garrick and Irish-born economist, philosopher, and statesman Edmund Burke.

These breakfast clubs got the name of Bluestockings from a man ironically, the botanist, translator and publisher Benjamin Stillingfleet, who didn’t have enough money to wear the customary black silk stockings for meetings of the breakfast club. He used to attend the gatherings wearing blue worsted stockings. Elizabeth Montagu came to be known as the ‘Queen of the Blues’.

The Bluestockings could hardly be called feminists. They were far from shaking the foundations of patriarchal society. ‘Feminism’ as a social movement only began decades later with the work of figures such as Mary Wollstonecraft. But Bluestockings did create spaces where upper-class English women could experience solidarity in expressing themselves independently. The Bluestocking Movement itself petered out towards the end of the 18th century but the word lingered on right up to the middle of the 20th century where it acquired a (sexist) humorous connotation with echoes of male contempt for intellectual women who neglect domestic duties for learning.

Two hundred and fifty years ago the term ‘bluestocking’ was a badge of honour for courageous, independent-minded women. Thank goodness that 250 years later most dictionaries now tag the word as archaic and derogatory.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel