As the world watches the tensions increase in Kiev, York art gallery owner Greg McGee looks back at the 10 months he spent teaching in Ukraine as a 21 year old in 1997

IF you were to play word association in 1997 and throw in ‘Kiev’, the response would invariably be ‘Chicken’.

As a 21 year old departing for a coach journey to live in Ukraine for ten months I held similarly dim views of my destination city.

I was heading out there to provide cultural contact and conversational skills to 50 young people. It was an unpaid role and my plan was to take a summer break on the Black Sea.

I decided on Ukraine because although it had a long, rich history, it was - at that moment in time - a blank canvas.

I knew that Kyiv (the now preferred spelling) had been a USSR communist city for decades, a fact which held its own dark glitter, but my young man’s antennae had also picked up the sense of a city being born right here, right now.

Leaving Spice Girls Britain for a city of possibilities was an easy choice to make.

My first impression was that no one in Kyiv had ever heard of Chicken Kiev. The second

was the architecture. USSR planners were not known for their flourish, but the Soviet insistence on sameness was surprisingly offset by huge examples of rococo and detailed facades.

Even in the midst of its post Second World War makeover, Kyiv had one eye on maintaining some kind of balance, it seemed.

Though the Lenin statues stared out from street corners, they felt more like a necessary recognition of recent heritage than potent political symbols.

Sumptuously baroque churches, chock-full of worshippers now the anti-religious persecutions of the state had abated, stood next to colossal war memorials that made 1998's Angel of the North back home in Tyneside look like an A-Level art installation.

Underground metro stations, some of the deepest in the world serving one and a half million daily passengers, displayed in mosaic the timeline of kings and saints from medieval glories. Zoloti Vorota Station hulked hugely, a replica of the giant fortifications which failed to keep out the invading forces of Batu Khan’s Mongols in 1240.

Black Mercedes saloons disgorged wannabe Mafia men on street corners to buy caffè Americanos.

It was this flinching willingness to fuse its ancient, recent and nascent identities that set Kyiv apart at the end of the century.

Cities in the UK were just starting to embrace homogenous anonymity, with the same bookstores, coffee shops, chain pubs, and anti-social stag parties that dilute them to this day.

Kyiv was simply up for seeing where the chips fell. The book shop that made me feel so welcome in January was a Drum and Bass nightclub by February; the Mexican Restaurant was a Cocktail Bar by March. Literature was a source of pride, with Kyiv’s Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita providing inspiration for The Rolling Stone’s Sympathy for the Devil.

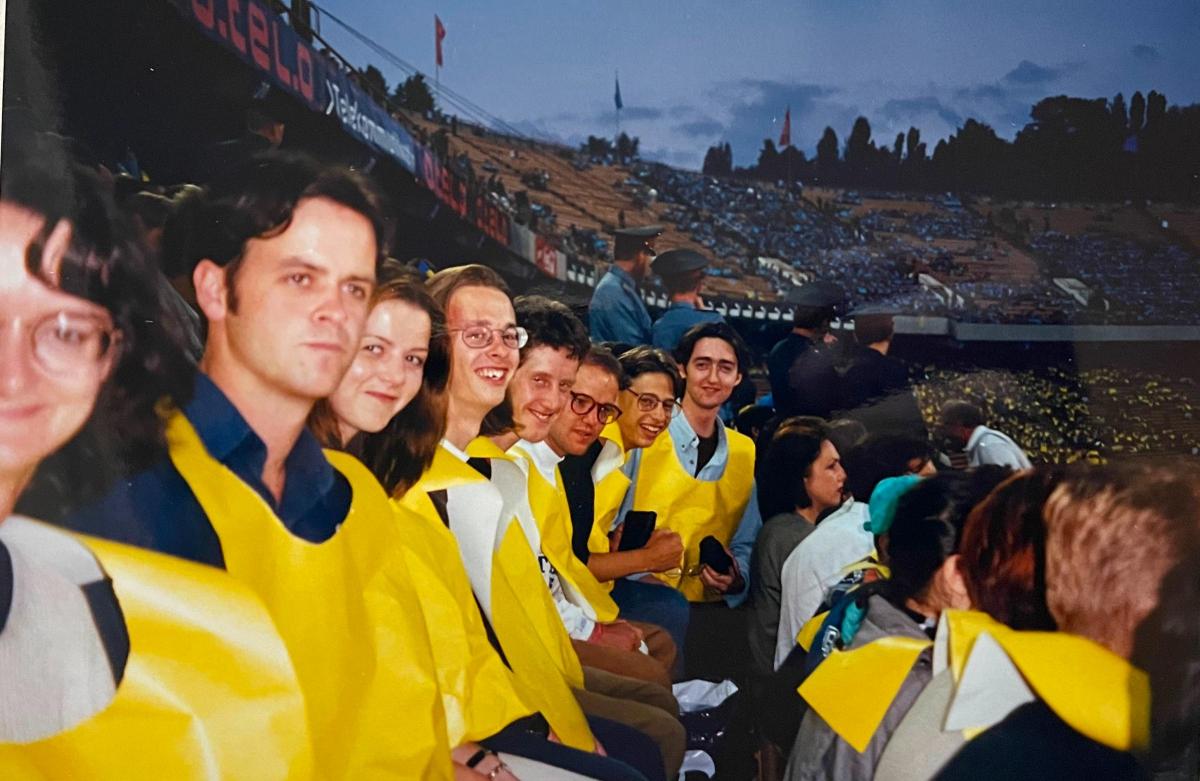

For 30p each week I watched the staple diet of operas and ballets at National Opera of Ukraine with local artist Dima and his crew. We had all become friends and we relaxed with Ukrainian beer (Obolon! Soft, rich, grainy) in new bars and clubs afterwards.

There was no denying the groundswell of independence that had gathered momentum since the fall of the Iron Curtain five years earlier. There was some nostalgia from some quarters for the rigorous certainties of the Soviet era, but increasingly the vibe over coffee, tea, vodka or McDonalds, was the excitement that came with closer assimilation with Europe, whether that meant becoming part of the EU or NATO.

The end of the most complicated century in this country’s see-saw history must surely bring with it the dawn of a new age of calm prosperity, we thought.

The Millennium was going to be a big deal for young Kyivites: they had been patient and philosophical, and they were at last due the turn of the wheel that had eluded them so long.

The Russians begged to differ. The 2014 invasion of Ukraine surprised everyone in its suddenness and the annexation of Crimea was as scary as it sounds.

If anywhere deserved to help helm Europe’s new cultural journey, it was Crimea. A simple overnight train trip from Kiev, I journeyed with fellow teachers Claire and Crichton and ended up staying there for the summer of ‘97. Hitchhiking from Yalta to Alushta to Sevastopol, we slept on pebble beaches and clubbed with locals, nightswimming with wild, free people in the subtropical Black Sea who helped me set up my first ever email address in internet cafes the next day. We bought single cigarettes from babushkas and drank beer in kiosks with stuntmen who had worked on ITV’s Sharpe, enjoying the stories of how Sean Bean and his co-stars partied harder than anyone they had ever met.

If you want Alexa to draw you a picture of a happy, hopeful 21-year-old man on the cusp of a country’s new chapter at the dawn of a new millennium, ask her to draw me in Crimea, summer 1997.

That beach now belongs to the Russian Federation. You can’t take a train trip from Kyiv without being barred from re-entering Ukraine, so best not make that trip. Images of Putin watch from huge billboards, promising to turn Crimea back into the spa-paradise of the Soviet Union.

To help hammer home his point, Russian warships bristle on Black Sea coasts.

Separatists, once in the minority and now, according to the ‘official’ referendum, 95 per cent in the majority, welcome back the warm wing of Mother Moscow. Annexation is utopia for the nostalgic separatist who saw only a vacuous disposal culture in the new EU friendly dawn to which my my friends and I raised a glass of vodka 25 years ago.

Annexation and invasion are very cosy bedfellows and Dima, my old mate in Kyiv, is watching current events play out with a numb sense of inevitability.

Already since 2014 there have been 14,000 deaths as separatists continue to seize control of the western regions.

Russian tanks and troops mass on the border. Fear is the primary emotion I expect as I ask him how he is this week. Dima, like me, runs an art gallery. His answer is a very Ukrainian potpourri of acceptance, indifference, watchfulness, irritation. "Our leaders are telling us not to panic. We are trying to tell our customers not to panic," he says, unintentionally paraphrasing Dad's Army.

"The Russians are saying 'don't panic.' But the UK is sending in its Prime Minister, Canada is sending its Defence Minister, ambassadors are running away. So you know what my clients are doing? Panicking. It's not good."

In Kyiv, cafes are staying shut, shops are closing, and the economy is suffering. Long used to being used as pawns in transcontinental games of chess, many Ukrainians prefer not knowing to panic, a survival instinct hewn from 1,000 years of conquest.

The 25 years since Dima and I shared a beer in Independence Square are just a pinprick of light in comparison. Dima chides: "A lot can happen in Ukraine over night. Please do continue to ask people to think about us. Awareness is good, panic not so good."

Dima had been planning to come to York for the first time this summer, a plan that has been shelved. He was hoping his first port of call would be a pint in York's oldest pub, Ye Olde Star Inn.

His second? "I need to try British cuisine. Book me a table in a restaurant that serves Chicken Kiev, I heard it's very nice."

Greg McGee is a photographer and charity director who co-owns the art gallery According to McGee in Tower Street, York, which he runs with his wife Ails. They live in York with their three children.

Tell us your story!

Do you have a real life story you would like to share? You can send it straight to our newsroom, with pictures, by clicking here or via the Send Now button below...

It happened to me: tell us your Real Life story

Do you have a moving or unusual personal story you would like to share with readers of The Press? You can send it straight to our newsroom - with photos - via the Send Now button below. Please include your name, email address and mobile number.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel