Just before 10pm on the night of Tuesday, May 8, 1849, a waterman by the name of Richard Booth was sailing a sand boat down the River Ouse near Marygate when he and his partner, Joseph Walker, spotted something in the water.

It was about 60 yards downriver, with dusk drawing in. At first they thought what they had seen was a duck. But as they drew closer they could make out that it was a man’s hat. Then, as they got closer still, they realised to their shock that there was a man under the hat, floating dead in the water.

Booth gave testimony at the subsequent inquest into the man’s death.

“I got into the boat and went to the object, and then found it was a man with his hat on, and that the hat was about half way above the water,” Richard told the inquest.

“He was nearly in an upright position, but his feet did not touch the bottom; the water there being about thirty feet deep.

“I and my partner pulled the man into the boat; I did not then know him. I put Walker (his partner) ashore, and he went in search of assistance; I then went down the river with the boat to Marygate end, taking the body in it.

“A surgeon came and saw the body in the boat; I had reached Marygate end about two or three minutes before the doctor arrived. After he had seen the body, it was taken to Walton’s public-house in Marygate.”

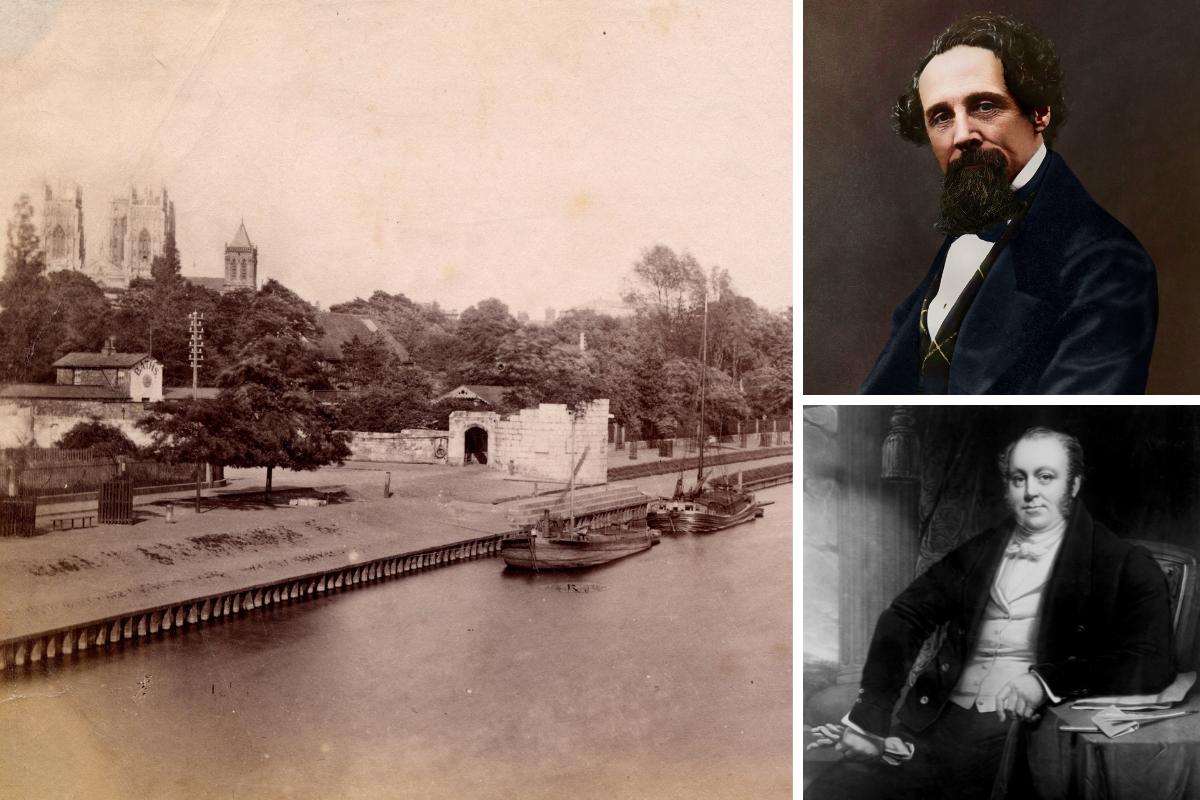

Barges moored at Marygate, near where Richard Nicholson's body was found. Image: Explore York libraries and archives

It is the detail that makes this long-ago tragedy so vivid. It is all-too-reminiscent of modern-day river tragedies: a reminder, if ever we needed one, of just how dangerous the River Ouse can be.

But there’s more to this particular case.

The body, it turned out, belonged to a a wealthy York man by the name of Richard Nicholson - a 56-year-old former linen draper who had invested heavily in the railways.

He was also the brother-in-law of the York ‘Railway King’ George Hudson - the Victorian entrepreneur who had done so much to bring the railways to the city.

But Hudson had fallen spectacularly from grace. A month before Nicholson’s death, a report exposed Hudson’s apparent wrong-doings over the value of his shares in the York & North Midland Railway. His fall was rapid. He went bankrupt, lost his seat as Sunderland MP, and was forced to live abroad to avoid arrest for debt.

The 'Railway King' George Hudson

He was not able to return to his native England until 1870, and died a year later, a broken man.

But it seems as though he may have taken his brother-in-law down with him when he fell.

Nicholson had been the auditor for the York & North Midland Railway. It seems plausible that, as news of Hudson’s disgrace spread, ruin may have beckoned for him, too - and that he may well have decided to end his own life.

That’s certainly what the York Herald of May 12, 1849, concluded.

“Numerous reports have been circulated as to the manner in which he got into the river, but the general opinion is that the present position of railway affairs has had a very depressing effect on his mind,” the newspaper reported.

The death of such a prominent citizen, in such tragic circumstances, caused quite a stir in the city.

“Considerable sensation was produced in this city ...by the report that ... Richard Nicholson, Esq., of Clifton, had been found drowned in the River Ouse about 150 or 200 yards from the Scarbro’ railway bridge,” the newspaper reported.

“On inquiring into the matter, it was found that this report was but too true, and what added greatly to the excitement which a knowledge of the fact produced, was the circumstance that, up to the time of his death, Mr. Nicholson acted in the capacity of director to the York, Newcastle, and Berwick Railway Company, the affairs of which have of late occupied so much of the public attention.

“Besides this, he was one of the auditors to the York and North Midland Railway Company, and the brother-in-law of Mr. Hudson.”

The newspaper went on to give a detailed report of the inquest into Mr Nicholson’s death - and several witnesses testified to the fact that he had been seen behaving strangely in the hours leading up to his death.

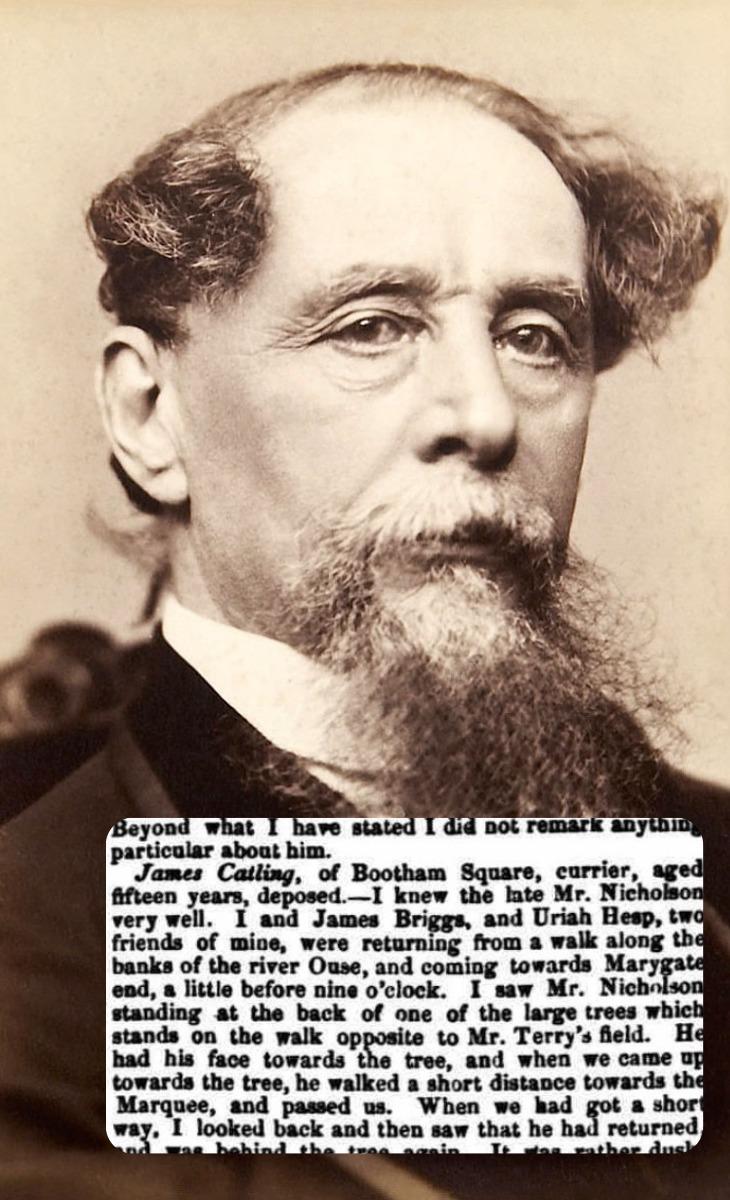

Extract from the York Herald's report of the inquest. You can see the name 'Uriah Hesp' - although because of a smudge it looks like Uriah Heap - or Heep

The dead man’s servant, John Reynard, said that Mr Nicholson had ‘not looked so well as he had done’ and ‘had not been so cheerful as he had been’ for a week or ten days.

“He has frequently gone in and out, and never seemed to rest in one place. For instance, when he has gone out for a walk he has returned in a short time, and he has also frequently gone up and down stairs, which he was not in the habit of doing,” he told the inquest.

York solicitor Martin Richardson described seeing Mr Nicholson walking beside the Ouse on the evening of his death. “He was walking slowly, in an apparently moody sort of manner, and his head was partly down,” he said.

Another witness, described only as ‘a juror’, also saw Mr Nicholson beside the river that evening. “Mr. Nicholson made no observation to us as we passed,” he said. “I thought he wished to avoid us, as he appeared to hide his face in the coat collar.”

Local historian John Shaw, the chair of the Yorkshire Architectural & York Archaeological Society (YAYAS), stumbled upon these accounts while doing some research about the Clifton area of York.

John Shaw

He found a reference to the sale of Nicholson’s Clifton house in 1849, connected the name with George Hudson’s brother-in-law, and began trawling through the online British Newspaper Archive.

It was there that he found the York Herald’s account of the tragedy.

There was one witness statement from the report of the inquest that particularly caught his eye, however.

It was given by 15-year-old James Catling, a currier or leather-worker.

James described how he and two friends were walking along the banks of the Ouse just before 9pm.

“I saw Mr Nicholson standing at the back of one of the large trees which stands on the walk opposite to Mr. Terry’s field. He had his face towards the tree, and when we came up he walked a short distance ... and passed us,” James said. “When we had got a short way, I looked back and then saw that he had returned, and was behind the tree again.”

What really caught John’s eye, however, was the name of one of the two friends who had been with James that night. His name was Uriah Hesp. But because of a smudge in the printer’s ink, it looked more like Uriah Heap - or Heep.

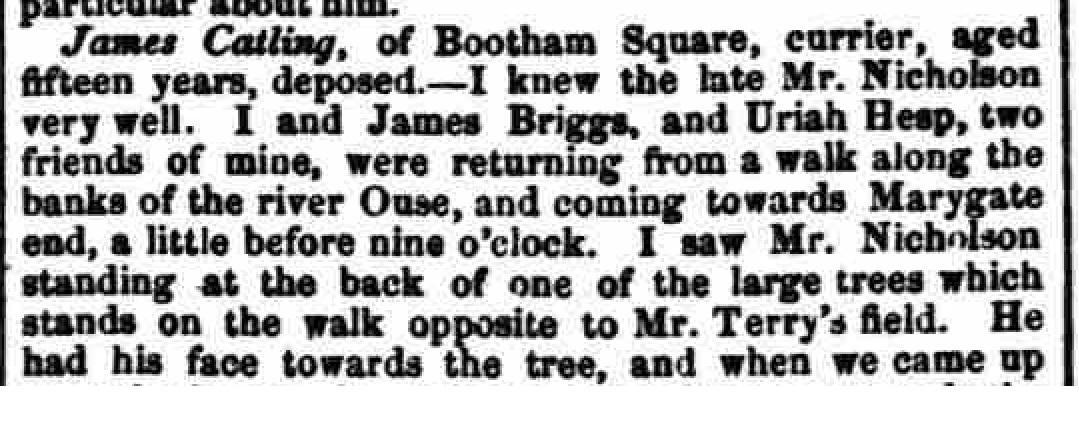

Charles Dickens published what many consider to be his greatest novel, David Copperfield, in serial form in a magazine between May 1849 and 1850.

Charles Dickens

The author’s brother Alfred was a railway engineer based in York. Dickens is known to have visited him in the late 1840s, and to have spent some time in York - in fact, a York & North Midland Railway clerk, Richard Chicken, is thought possibly to have been the model for Dickens’ Mr Micawber, one of the many great characters in David Copperfield.

Another unforgettable character in the novel, however, is an ‘ever so ‘umble’ clerk named Uriah Heep, who turns out to be a vicious hypocrite and bully.

So might Dickens have read this account of Nicholson’s death during a visit to York, come across the name of Uriah Hesp/Heap/Heep, and used it in his new novel?

John thinks he may well have done. The author was spending a lot of time in York, and his brother was in the railway business, so would have been interested in Nicholson.

“And the timing is spot on!” John said.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here