INFLUENCED by the gloriously ridiculous B-movie imagery of the Fifties and Sixties, York artist Lincoln Lightfoot questions what might be in store for 2021.

You can see his humorously absurdist answers when he makes his York Open Studios debut this summer, after the 20th anniversary show was moved from April to July 10/11 and 17/18.

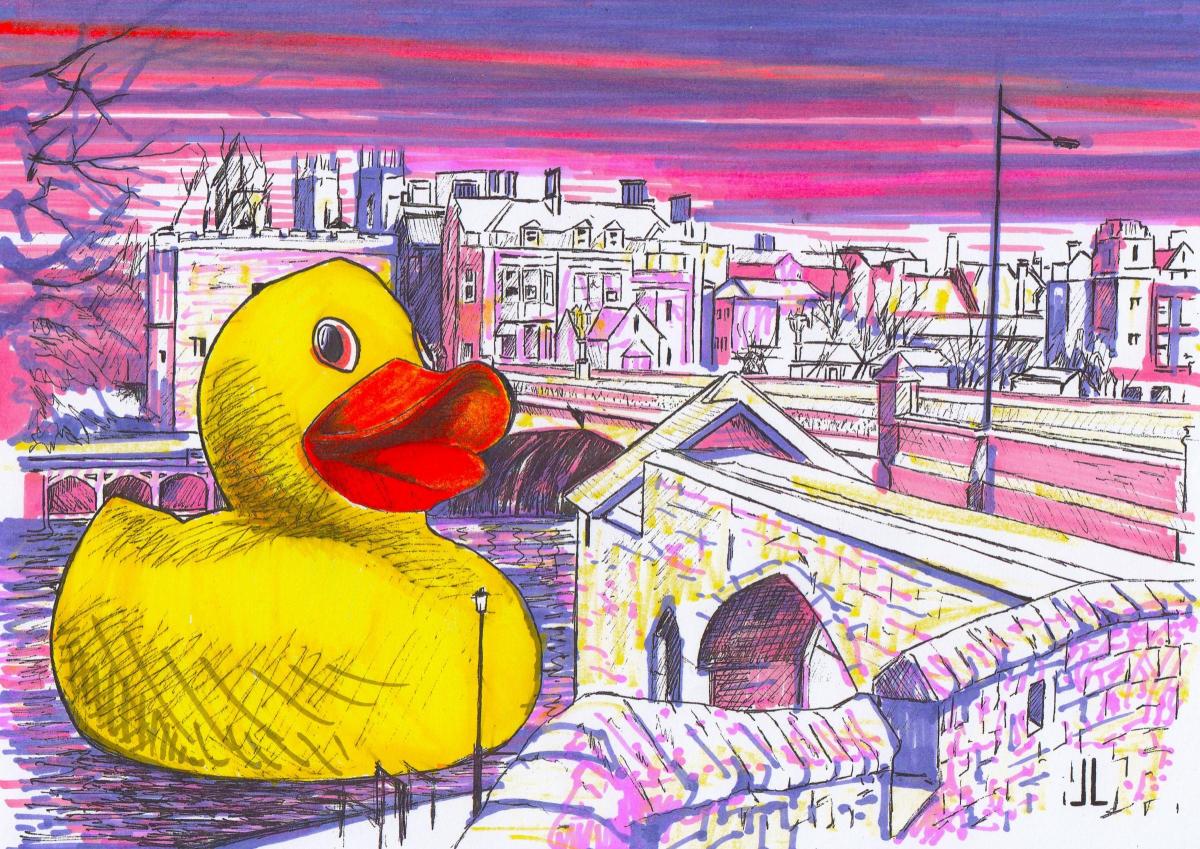

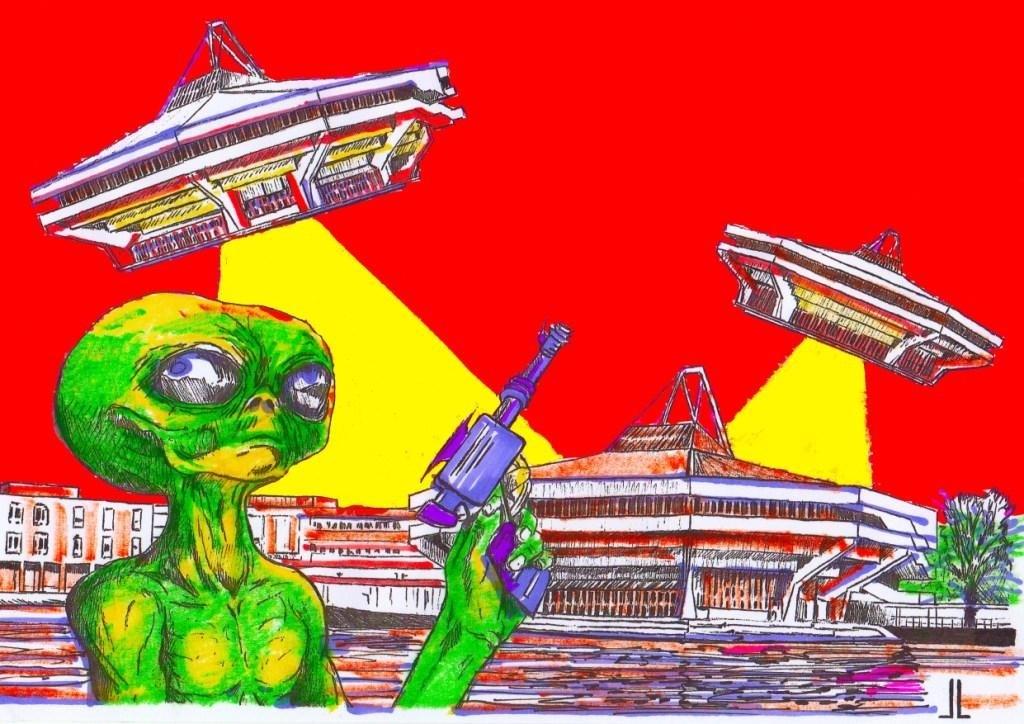

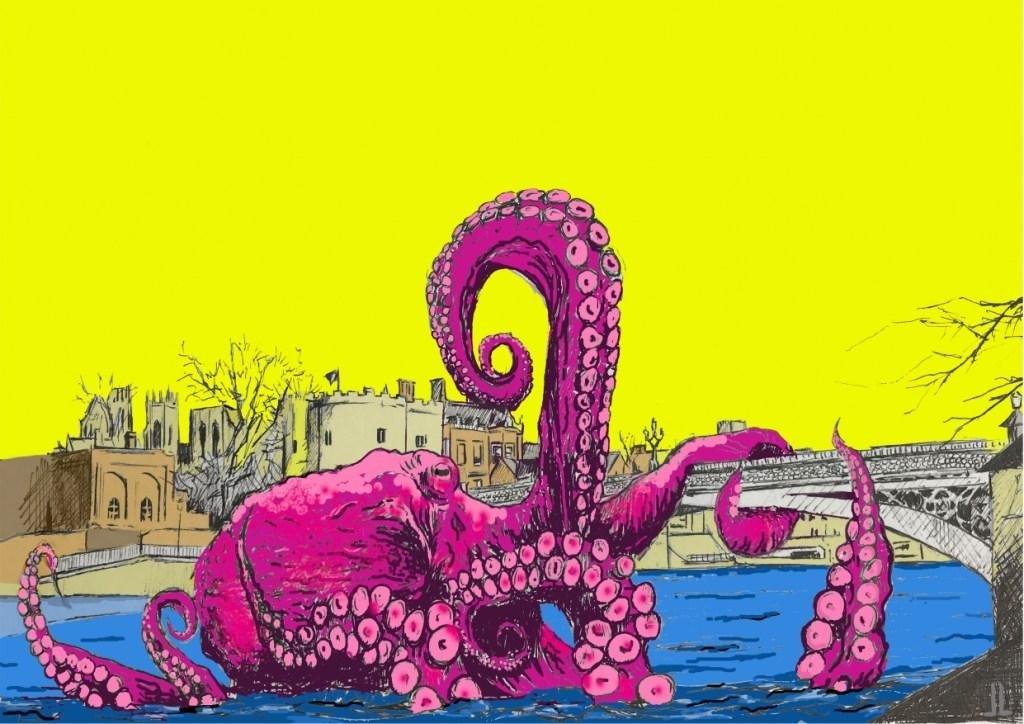

Lincoln’s digital-print images and oil paintings take the broad theme of surreal encounters with beasts that appear in recognisable locations: not so much King Kong climbing the Empire State Building in New York as a tentacled Creature From The Bottom Of The Ouse clambering on to a bridge in York.

The South Bank artist’s outre artwork is at once playful yet plays on our worst nightmares too. “I’ve always believed that through the consumption of art, we can deal with nightmares and perceived dangers safely,” says 28-year-old Lincoln.

“As children, we confront and make sense of a dangerous world through fairy stories and nursery rhymes. Young people wish to be told of danger through anecdote and myth in a safe space. I attempt to continue this addiction and appeal to adults too.”

Born in Hartlepool in 1992, the son of a school head of art and design, Lincoln was always fascinated by art, heading to York St John University to study Fine Art, whereupon the city’s streets, buildings and passageways became the centre of his work and remain so.

“It’s a story-book city, conjuring up tales of the past. Walking through its streets, your creative mind can just let loose and go to work. It’s not hard to imagine incredible things happening there because they already have,” he says.

Lincoln has been enamoured with the city since childhood days. “My grandparents used to take me and my brother on caravan trips. I remember staying at Rowntree Park a number of times,” he recalls.

“I loved the untouched feel of the city, the idea that things within the city had been there for hundreds of years. I still can’t get enough of it. Every time I’m in town, I see something new, something that fascinates me. I’m often left saying, ‘How come I haven’t seen that before?’.

“I’m in awe of York Minster, the intricate beauty of the architecture and our overwhelming insignificance next to it.”

York has to live with the chain of history around its neck, but Lincoln’s art makes you look at the city in a different light, in the tradition of artists being outsiders. “Lots of artists are drawn to the city as a subject because of its historical architecture and picturesque views. It's a path well-trodden,” he says.

“I'm currently playing around with a series of giant oil paintings that would strive to be similar to the style of [English Romantic painter, illustrator and engraver] John Martin's biblical end-of-the-world scenes. I guess in some ways, if executed with a high enough level of skill, they could be seen to poke fun at high art.

“I love the stories of John Martin's work; for contemporaries it would be like a modern-day visit to the cinema, maybe even more emotive. People would scream before them in horror. (Ironically his brother, ‘Mad Martin’, was a non-conformist who set fire to York Minster on February 1 1829).

“People often go in search of escapism, fascinated by unconventional ideas or elaborate fantasy worlds. That's what makes B-Movie poster art so attractive. To strip it back to a recognisable location can only make it more appealing.”

Far too many events and experiences are described as “surreal” but Lincoln’s fantastical work absolutely fits the description. “Contemporary Surrealism addresses people’s worries and stresses and provides an escape into an alternative world and helps us cope with anxiety in safe and sometimes humorous ways in these times of isolation and stress,” he says.

“It differs from the pioneers of the 1920s and 1930s with the advances in film and graphic media. We have the tools to blur reality with fantasy even more convincingly.”

Not only an artist but also an art and design teacher in Sunderland, how has Lincoln coped with fear-filled pandemic lockdown times? “Life in lockdown has been kind when contrasting with others. It has afforded me time to reflect and take stock of where I might be going as an artist and art educator,” he says.

“Walking around York, seeing the streets and alleyways otherwise populated with people, now deserted, has reinforced my practice in a profound way.

“Many of the documented photographs I took could lead to future ideas. Initially, it’s a time where the word ‘surreal’ may be justified. I’m still expecting to wake up in March 2020.”

As he prepares for his York Open Studios debut, Lincoln says: “Watch out for more of my fantastical beings invading York’s ancient places. I’m now working on larger-scale oil paintings that use chiaroscuro not associated with Pop Art, but use blending and glazing. The best of these will be made into Giclee limited-edition prints.”

One final question: what exactly is in store for 2021 for you and the rest of us, Lincoln? “Aliens, man, definitely aliens,” he says. “There are more influential individuals making statements and releasing information by the day.”

Lincoln Lightfoot will be opening his doors at 118 Brunswick Street, South Bank, York, for York Open Studios 2021 on July 10/11 and July 17/18, 10am to 5pm. For details of all York Open Studios artists, visit yorkopenstudios.co.uk.

Should you be wondering: how did the fabulously alliterative name Lincoln Lightfoot come about? “I have an American mother from Chicago, which people are often quick to assume is the reason for my name (Abe Lincoln). However, it was my father who came up with it,” reveals Lincoln.

“‘Lincoln’ is Old English, meaning ‘the place by the pool’, and I was born in Hartlepool, which has the same meaning. My Dad loves to explain this…and gets an eye roll from me!”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel