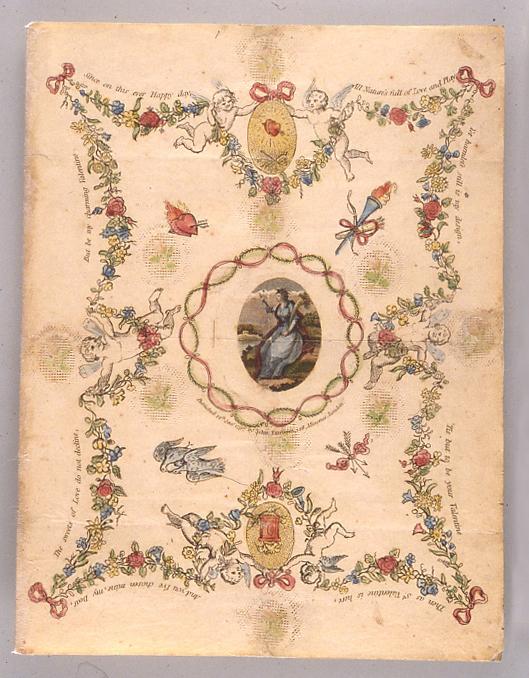

On St Valentine’s Day 1797, a certain Mr Brown received a card from a Miss Catherine Mossday of Dover Place, Kent Road.

It was a very plush card, the front illustrated with cupids, pierced hearts and lovebirds, and with an elegant portrait of a seated woman in the centre. Around the edge was printed a sentimental verse: “Since on this ever Happy day, All Nature’s full of Love and Play, Yet harmless still is my design, ’Tis but to be your Valentine.”

The massage written inside was anything but sentimental, however. Miss Mossday was clearly more than a little annoyed with the object of her affections. “Mr Brown, as I have repeatedly requested you to come, I think you must have some reason for not complying with my request,” she wrote.

“But as I have something particular to say to you I could wish you make it all agreeable to come on Sunday next without fail and in so doing you will oblige your well wisher - Catherine Mossday.”

The icy blast of Catherine’s disappointment and disapproval can be clearly felt even after more than two centuries. It is perhaps not hard to imagine why she was disappointed. But did Mr Brown keep the appointment? And if so, what happened?

Sadly, we’ll never know. But this card - believed to be the oldest printed Valentine’s Card still in existence and now part of the York Castle Museum’s extensive collection of such cards - suggests that, for the Georgians just as for us, the course of true love didn’t always run true.

And that for them, just as for us, Valentine’s Day could be a cause of pain as much as joy.

The origins of Valentine’s Day are shrouded in mystery. It seems to have originated in Roman times as a Christian feast day honouring one or two early Christian martyrs named Saint Valentine.

Just who Valentine was is a matter of debate. There are several contenders, including a priest imprisoned for ministering to Christians persecuted under the Roman Empire in the third century.

According to one legend, this Saint Valentine restored sight to his jailer’s blind daughter. An 18th-century embellishment of the legend claims he wrote the jailer’s daughter a letter signed ‘Your Valentine’ as a farewell before his execution.

Another legend claims that a Saint Valentine performed weddings for Christian soldiers who had been forbidden to marry because the Emperor Claudius II decided that single men made better soldiers than those with wives and families. How very Night's Watch.

Whoever the real Saint Valentine was, the feast that bears his name seems to have been established by Pope Gelasius I in AD 496, who apparently ruled that it should be celebrated on February 14 in honour of the saint’s birthday.

February 14 wasn’t originally a day devoted to celebrating romantic love, however. That seems to have come in the middle ages - in the 14th and 15th centuries, when notions of ‘courtly love’ flourished.

What we do know is that by Georgian times, the practice of exchanging cards on Valentine’s Day was becoming fairly normal - though, as Miss Mossday’s card to Mr Brown suggests, they weren't always used simply as an expression of affection.

The giving and receiving of Valentine’s Cards really took off, in England at least, in Victorian times, however - in 1840, in fact, when the penny post was launched.

That made it affordable to exchange cards, says Helen Thornton, the curator in charge of the Castle Museum’s extensive Valentine’s Card collection.

Most of the museum’s cards date from the Victorian age. And there's a real range - from the sentimental and the humorous to the downright cynical and even malicious.

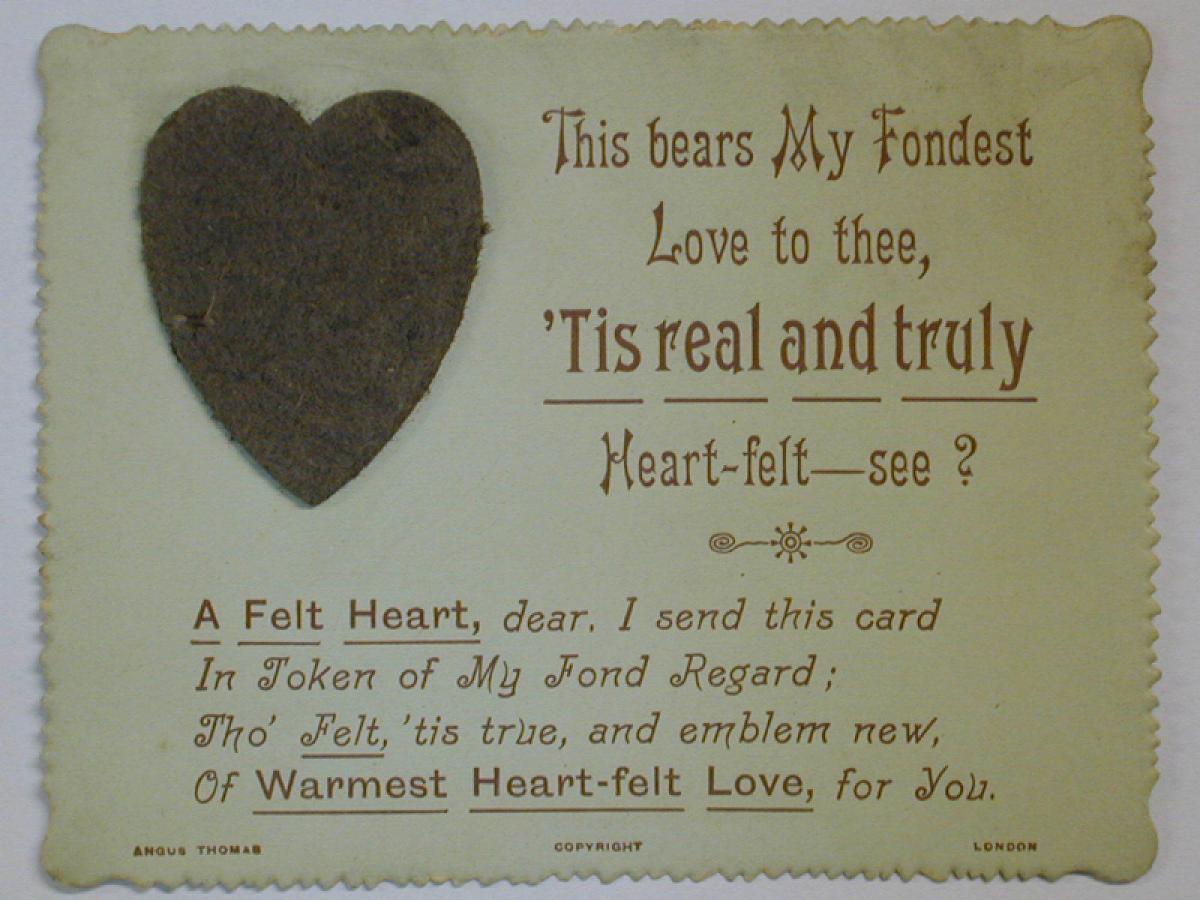

On the sentimental side, there's one card that underlines the heartfelt nature of the sender's feelings by being decorated with a heart - made out of felt. There's also an elegant, five-leafed fan, each leaf of which is embellished with delicate colour illustrations of flowers, and sentimental rhymes.

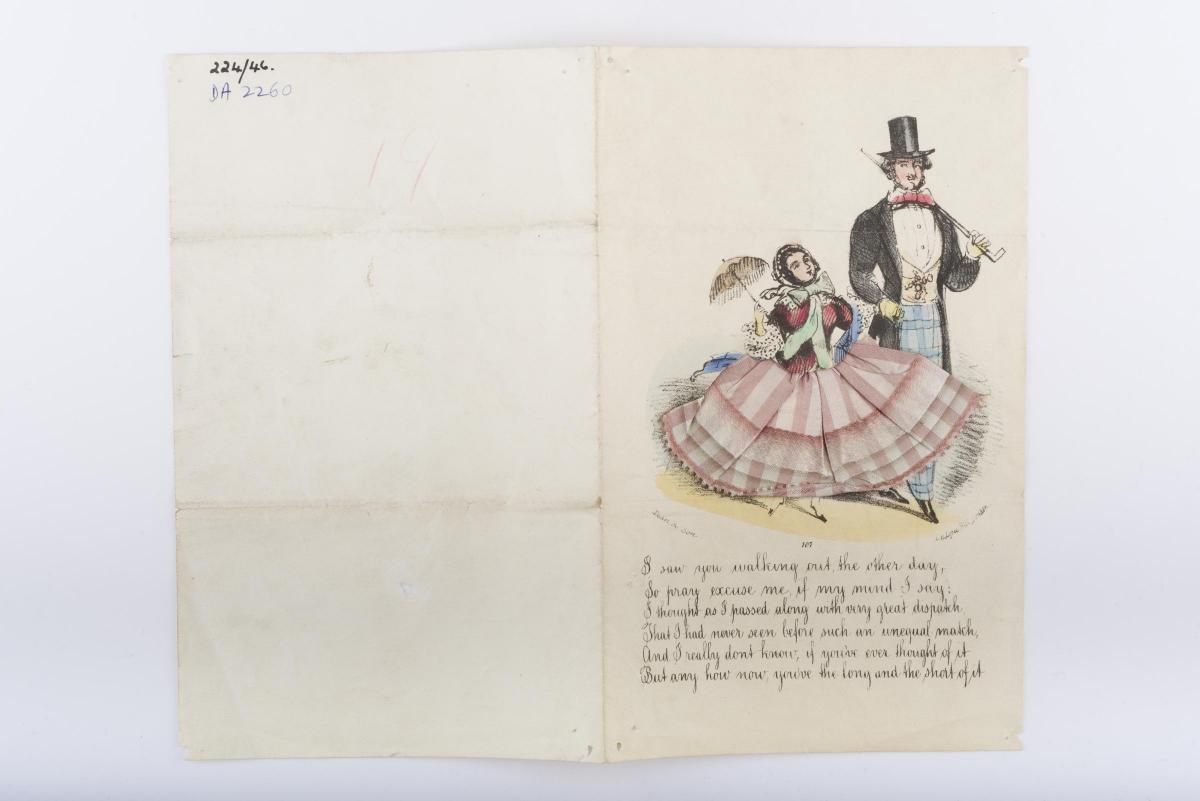

On the humorous side, there's one card which shows a tall, elegant man squiring a much shorter, but well-dressed woman (her skirt is made of real fabric). "I saw you walking out the other day" says a rhyme. "You're the long and the short of it."

It's the cynical cards that will get a laugh out of most of us today, though.

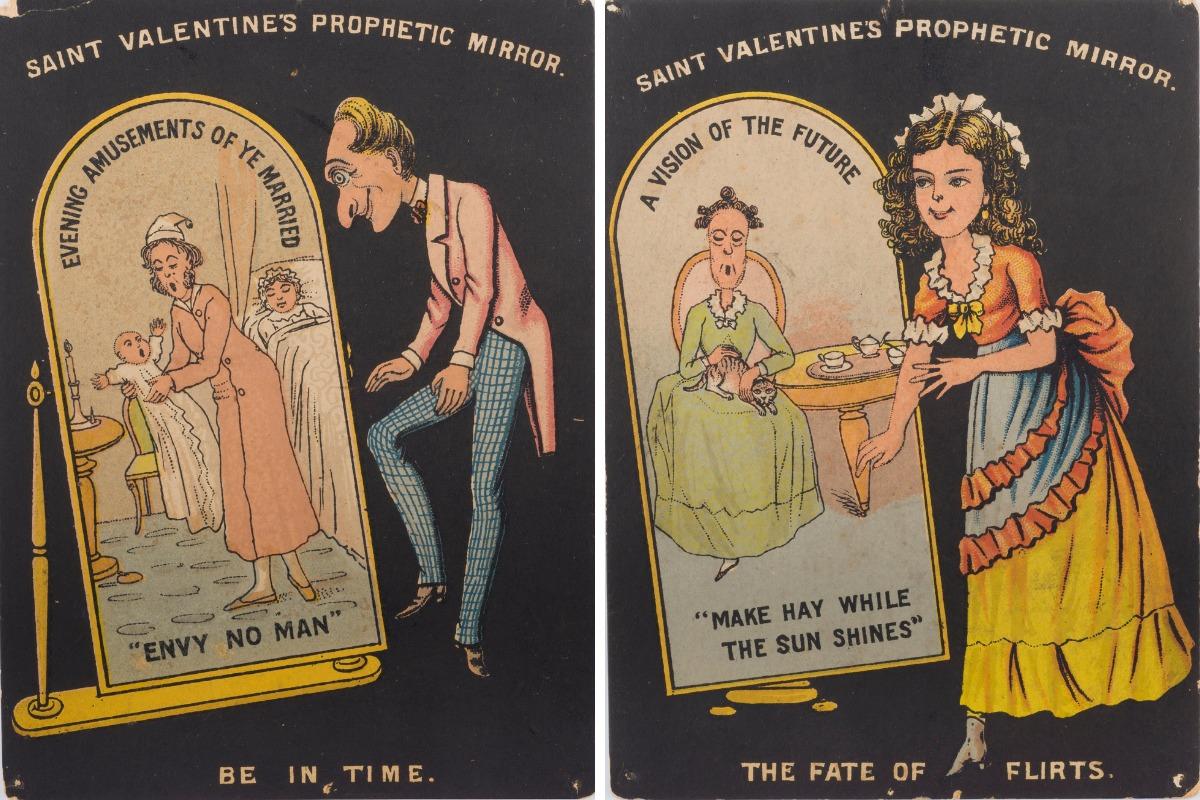

The museum has a set of cheap, printed cards that are part of a series called 'Saint Valentine's Prophetic Mirror'.

Each depicts a character gazing into a mirror which shows their future. In one, a man-about-town peers into a mirror which shows his future wife looking after a screaming baby. 'Envy no man', it says.

Even worse is a card which shows a pretty young woman gazing into a mirror which shows her as a lonely, elderly spinster with just a cat for comfort. 'A vision of the future,' the card says. 'The fate of flirts''.

It is clearly intended as a warning to a flirtatious young woman that if she's not careful, she will ruin her reputation - and so her chances in the marriage market.

Ouch! Now that's just nasty - an example of Victorian moralising and cruelty all wrapped up into one mean little package. Hard to imagine anyone sending that to someone they claimed to be fond of.

With the museum closed at the moment due to Covid, you sadly won't be able to see any of these cards for yourself for a while. But the museum plans to post some of them on social media. So watch out for them on its twitter and facebook feeds...

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel