Widespread poverty in the countryside in Elizabethan times drove beggars towards the relative honeypot of York. To deal with this, the corporation took a census of the poor and issued begging licences.

From 1515, beggars certified as legal had to wear tokens on their shoulders. By 1528 a hierarchy of beggars was established, according to the History of York website. To each ward was appointed a ‘Master Beggar’ who kept an eye on the rest. Any without a token were told to leave.

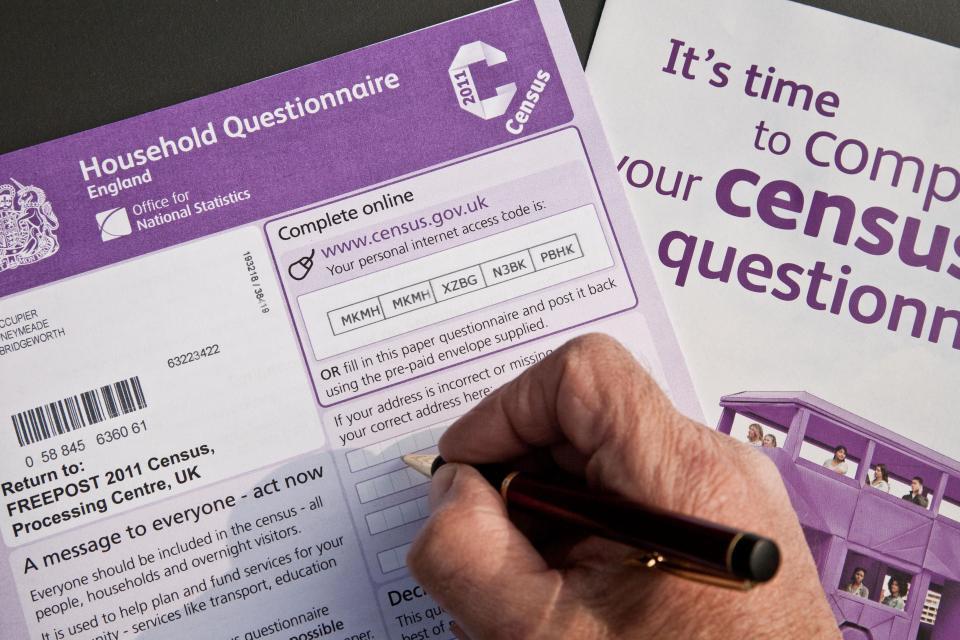

The census we know today happens every ten years and provides invaluable information about all the people and households in England and Wales.

It’s been running for 200 years, although no census was taken in 1941, during the Second World War.

The next census takes place on March 21. This will help to calculate what our needs are now and predict what they are likely to be in the future. It will also preserve for future generations a snapshot of how we live now.

Interesting historical snippets about York nestle in the layers of the census. These chart how the city has grown and changed, showing how outlying districts and villages were drawn into the city during the 20th century.

The village of Acomb, for example, had fewer than 1,000 residents in the 1871 census. That had risen to 7,500 when Acomb was incorporated into the city of York in 1937 (the writer of this article was incorporated there about ten years ago).

The dominance of York’s two great industries, confectionery and the railways, was clear for much of the century.

By the time of the 1911 census, confectionery employed around 3,700 people, a figure that rose to more than 12,200 by 1940. Around 30 per cent of the working population were women – and more than half the jobs were held by women. The railways employed 13 per cent.

While the census is avowedly apolitical, it has in the past run up against the politics of the day. Witness a blue plaque put up on Coney Street by York Civic Trust in January, 2019. This marks the location of the headquarters in York of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

As the trust historian Pat Hill points out: “The rally call for the 1911 Census by Emmeline Pankhurst and others was, ‘If women don’t vote neither should they be counted’ and women were encouraged to evade the census.

“In York the historical background to the plaque recounts women who are not enumerated on the census.”

The census became a cause for the women known as Suffragettes. This term was coined in January 1906 by the Daily Mail newspaper; it was intended to belittle and demean the militant campaigners, but they adopted it as a badge of honour.

Among those who evaded the 1911 census in York was Annie Coultate.

The census enumerator wrote on the form for her address at No.33 Melbourne Street that she “was away from home during the night of the Census, but was most probably enumerated amongst a number of Suffragettes who passed the night in a room in Coney St, York, with the object of evading the Census”.

In London, a leading Suffragette engaged in more elaborate disruption.

Emily Wilding Davison ensured she was counted twice. “Once while hiding in a cupboard in Parliament in 1911 and once by her landlady,” says Pete Benton, director of census and survey operations.

“This was discovered after 100 years when the records were made public.”

The 1911 census recorded for the first time the number of years a woman had been married. It also recorded her children, living and dead. The growing Votes for Women movement saw opposing the census as a campaign tool.

Not everyone was impressed with this tactic.

The educational reformer Professor Michael Sadler of Manchester University wrote in a letter to The Times on February 14 1911 that “to boycott the census would be a crime against science” because future legislation to improve the conditions for all people depending on a complete census.

Thousands of visitors and tourists to Kirkgate, the Victorian street in York Castle Museum, have benefitted from investigative use of census records.

Dr M Faye Prior supervised a team of volunteers who wrote a guide to the Victorian street.

“All the shops and other businesses are based on actual businesses that operated in York between 1870 and 1901,” says Dr Prior. “Our volunteers did a lot of work looking into census records.”

The cutler and the taxidermist, the York Temperance Club and Cocoa Rooms, the hair-cutter and tobacconist; all of these and many others were recreated with the help of the census.

As the census aims to record a true picture of our society, the questions change with the times.

For instance, households used to be asked if they had an outside toilet. That question ran from 1951, when nocturnal dashes to the lavatory will have been chilly, all the way to centrally-heated 1991.

Census 2021 will include questions about your age, work, health, education, household size and ethnicity.

For the first time, people will be asked whether they have served in the armed forces.

And there will be voluntary questions for those aged 16 and over on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Anyone who wishes to answer the sexual orientation and gender identity questions without letting others in their household see their answers can request a separate form.

Census 2021 is a digital first census and you will be able to complete the questionnaire on your tablet, smartphone or computer.

Every household will be sent a letter with a digital access code to allow online access for all members of that household.

Digital access has been made as easy to follow as possible. But don’t worry if you are not able to complete online, as paper copies will still be available.

You can fill in the questionnaire before, on or after March 21, but it is the law that you do complete the census. Failure to do so risks a fine of £1,000, although that very rarely happens.

All information is stored anonymously, so there is no risk of you being identified from anything you write on the questionnaire.

While the information gathered will be shared about a year after the census, all names will remain hidden for 100 years.

Those details will be kept safe for future generations. Or for researchers on long-distant episodes of the TV favourite Who Do You Think You Are?

Julian Cole, a former Press journalist, is the census engagement manager for York, Ryedale and Scarborough. More information at census.gov.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel