At 2:42am on April 29, 1942, an air-raid siren began to sound in York. The city was about to experience its worst night of the Second World War.

For two hours or more, German aeroplanes flying overhead rained bombs down on the city.

By the time the final all-clear sounded at about 4.45am, 94 men, women and children in the city and its suburbs had been killed, or left so badly injured they were later to die. A further 15 British military personnel died in the raid, as did six German airmen.

The raid began with flares and incendiary bombs. The latter were dropped in areas such as Pickering Terrace, Bootham Terrace, and Queen Anne’s Road. The incendiary bombs, however, were only the beginning. In fact, they lighted up more targets.

The 69 high explosive bombs (10 of which did not explode), which followed the incendiary ones, were what killed most people.

And in addition to the appalling human toll, many buildings across York were badly damaged.

They included York Railway Station, The Guildhall, St Martin’s Church on Coney Street and the Bar Convent.

Several survivors of the raid were later able to give detailed eye-witness accounts of what it was like that night. We include some of their stories here...

David Wilson

ONE of the enduring images from the night the bombs rained down on York was of the fire-gutted Guildhall the morning after the raid.

David Wilson and his family lived at the Guildhall, where David’s father Jock was the caretaker and sword-bearer. They were there the night the bombs fell – and they survived to tell their story.

David, who was 11 at the time, recalled that night in an interview he gave to The Press a few years ago.

The family lived in the caretaker’s flat, on the second floor above the Victorian municipal offices next to the medieval Guildhall itself.

David remembered the Observer Corps’ warning bell going off, followed by the sirens. With that, all hell broke loose.

The bombs raining down on the Guildhall were only incendiaries – but explosive bombs fell on Blake Street, not far away.

David, his mum and his older sister Margaret, who was in the ATS, went down to the supposedly bomb-proof ARP headquarters in the basement.

But his dad was on fire watch – and stayed above, vainly trying to tackle the flames.

The roof of the Guildhall had been undergoing repairs. There was a floor of new timber just beneath it so that workmen could reach it, plus scaffolding and shavings. When the incendiaries landed, it all went up in flames.

“The whole thing was a tinderbox,” David told The Press.

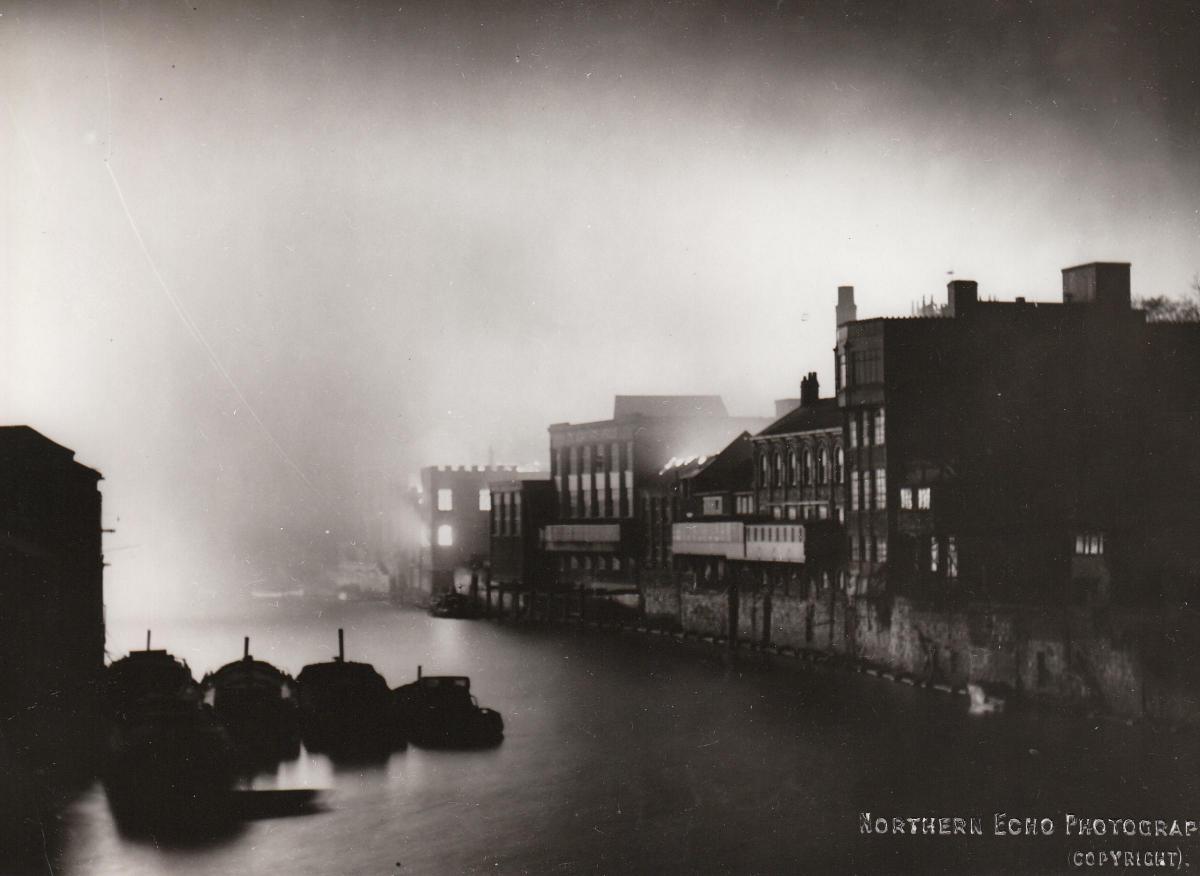

David’s own most vivid memory was of going out onto the balcony overlooking the river behind the Guildhall. From there, it seemed as though the whole riverfront was on fire: the Guildhall, and buildings on the opposite side of the river too.

It was frightening, he admitted – but a sight he wouldn’t have missed. “You’d never, ever see that again.”

Eventually, as the fires at the Guildhall burned more fiercely, the family was evacuated to the Mansion House.

Margaret was in her ATS uniform, and wearing a tin hat. It was fortunate that she was. As they walked along the passage beside the Guildhall, lead dripped off the roof and on to his sister’s head.

Harold Wood

Harold, who was just 18 in 1942, was part of a five-man Home Guard team on duty at the Lendal post office the night the bombs fell.The unit consisted of a sergeant and four men. They were armed with a rifle and five rounds of ammunition.

At 2.38am, German bombers appeared in the night sky and began raining bombs - both explosive and incendiary - down on the city. “The incendiaries rained down with a terrific clatter as they ricocheted off roof-tops and buildings, spitting fire,” Harold recalled, in an interview with The Press last year.

He and his team first used buckets of water and a stirrup pump to put out a fire at a shop opposite the post office. Then they rushed to do the same at the telephone exchange, which was also on fire.Then it was back to the post office in Lendal, where the regular night cleaner, Charles Bartle, had appealed for help.

“Armed to the teeth with two stirrup pumps and as many buckets of water as we could carry, we followed him to the top of the building,” Harold recalled. They dashed from one rooftop to another, up ladders and down wooden steps, extinguishing fires wherever they found them. By the time the All Clear sounded at 4.30am, more than 100 people were dead or dying, the Guildhall was in ruins, and 9,500 homes had been destroyed. But the post office had survived.

Edna Annie Crichton

Cometh the hour, cometh the woman. That was certainly the case with York’s first-ever female Lord Mayor, Edna Annie Crichton.

Her term of office ran from 1941-1942 - and so it was she who led the city through the aftermath of the York Blitz.

Edna - whose husband, David Sprunt Crichton, was the first welfare officer at the Rowntree Cocoa Works - stood for election to York City Council in 1919, arguing that women were more knowledgeable than men ‘in such questions as housing, education, maternity and child welfare’. She topped the poll in Bootham, was elected chair of the council’s housing committee in 1931, and chaired the committee for 20 years.

In 1941, she was elected York’s first woman Lord Mayor. Her year in office was to prove the most dramatic in York’s modern history. In addition to the toll of dead and injured in the Blitz, up to a third of the city’s homes were destroyed or damaged. The Lord Mayor visited bombed home after bombed home.The Yorkshire Evening Press of April 30, 1942, said she had been “an inspiration to the citizens, working untiringly ... superintending ARP arrangements, visiting hospitals and first-aid posts and generally alleviating distress.”

Edna remained on the council for 10 years after the war before retiring. She died in a York nursing home in 1970, aged 93.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel