AT 10am in the morning on a March day in 1965, three York women sealed themselves in a makeshift nuclear bunker at The Guildhall, and prepared to wait out the end of the world...

Well, they didn't really. It was all an experiment, designed to test out the city's cold war defences - and the official government guidance on what to do in the event of a nuclear strike. But it was guidance that really did need testing.

In 1965, according to a fascinating article written by Taras Young for History Today in 2018, the UK government was primed for nuclear war. "Evacuation plans were in place, strategic food stockpiles teemed with corned beef, flour, sugar and fat, and the government was engaged in a nationwide spate of bunker-building," Young wrote.

In York, a small, three-person bunker had been built in Fulford in 1961 for use by the Royal Observer Corps (ROC), the volunteer organisation charged with watching the skies and - if the worst came to the worst - measuring and reporting nuclear explosions.

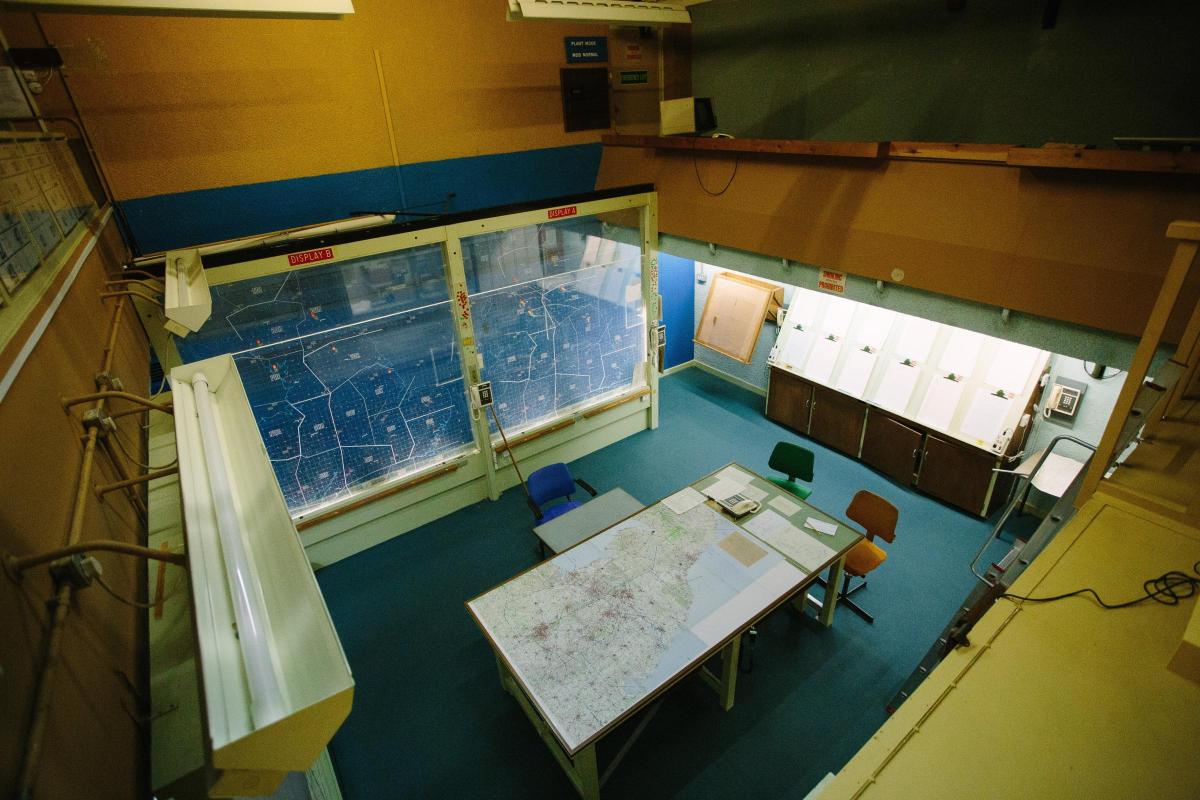

The bunker was just part of a huge network of more than 1,500 underground monitoring posts constructed across the UK. Later in the same year, a bunker three levels deep was built at Acomb, in the York suburbs. The 'Cold War bunker', as it is known today, still survives, and can be visited by arrangement with English Heritage - though not, of course, until our own lockdown is over.

Entrance to York's cold war bunker in Acomb

The official guidance for ordinary members of the public about what to do in the event of a nuclear attack in 1965 took the form of a public information booklet, Advising the Householder on Protection against Nuclear Attack - officially known as Civil Defence Handbook No. 10.

To us, today, this looks hopelessly naive and ill-informed.

"The penetration of the harmful radiations from fall-out is reduced by heavy and dense materials such as broken walls, concrete or hard-packed earth," the booklet explained. "You should try to get as much of this sort of material between yourself and the fall-out as possible. A cellar or basement gives most protection."

There was advice on how to prepare your house to survive a nuclear blast. "The H-bomb's heat could not set fire to the brick or stone of a house but, striking through unprotected windows, it could set fire to the contents," the booklet warned. "Whitewash your windows.The whitewash will greatly reduce the fire risk by reflecting away much of the heat."

As for how you should stock your home-made fall-out shelter, Civic Defence Handbook No 10 suggested mattresses, pillows, blankets, plates, cups, knives and forks, rubber or plastic gloves, sanitary towels, first aid kits, books and magazines, children's toys and an 'emergency reserve of tinned or other non-perishable food... to last for at least fourteen days'.

Cover of 'Civil Defence Handbook No 10'

It was all very Raymond Briggs - although the author's classic picture-novel When The Wind Blows, about an ordinary couple trying to sit our a nuclear war by following government advice, wasn't published until 1982.

Still, York's Civil Defence Committee clearly felt the government advice needed to be tested. And so it was that the three volunteers - Margaret Jones, 34, and Winifred Smith and Mildred Veale, both 40 – entered the shelter; an anonymous outbuilding near the Guildhall which contained a fully prepared fallout room designed to offer basic protection against the radioactive dust that would fall over York in the event of a nuclear strike on Leeds.

Here, they holed themselves up for 48 hours - thought to be the minimum time needed for the danger from the radioactive dust to subside - with no electricity, little food, and a radio set that played seven pre-recorded emergency messages.

The three women soon learned that even 48 hours in 'lockdown' in such closed, cramped conditions could test the strongest resolve.

Speaking to the then Yorkshire Evening Press on the day the experiment began, the three were upbeat. But two days later, they all reported to be suffering from soreness, hallucinations, misery and boredom as the impact of being holed up in the 9ft by 13ft room took effect.

“I kept thinking the shelter was going to fall in,” Miss Veale told the newspaper, on emerging into daylight for the first time in two days.

Young goes into more detail about the three women's experience.

"The space was about the same size as a normal living room. It had been kitted out with a table, chairs, cupboards and bookshelves... No light came through the windows, which had been whitewashed to the specifications of the government handbook.

"At one end of the room was a lean-to shelter core... made by propping a couple of doors up against the wall, reinforced by ... sandbags. The core measured just three by five feet... The women ...would need to stay (there) for seven hours in order to avoid the most damaging effects of the ‘fallout’. The Times reported that they managed six-and-a-half uncomfortable hours ... before emerging, suffering from cramps."

In the end, though, it was the boredom that got to them as much as anything.

"They did nothing but exist; the minimum of cooking, but nothing else whatever," Young wrote. "Simulated radio news broadcasts, pre-recorded to tape...were played via the fallout room’s wireless set...If the broadcasts were meant to make them feel better, it did not work: once the news had finished, the volunteers became ‘more miserable and isolated’. They tried to do some knitting, but made so many mistakes they had to give up...They went to bed, but found themselves unable to sleep..."

No wonder they were so disoriented by the time they came out.

So what parallels are there, if any, between these women's experiences and our own lives under lockdown? And is there anything we can learn?

Mark Roodhouse, a Reader in modern history at the University of York, stresses that the government advice which looks so ridiculous to us now was probably never intended to do more than stop people panicking.

Mark Roodhouse

"It was about reassuring people," he says. Realistically, officials must have known that many people would not survive a nuclear war. But they could hardly go around telling people that...

Does that mean that the official advice we're being given today is also worthless?

Well, no, Mark admits. The advice to stay at home, self-isolate and only go out if you have to is all very sensible. "And it does seem to have been working on the whole."

But he has also been struck by how unprepared the government seemed in other respects.

"They don't seem to have recognised in advance the consequences of that advice for some ordinary people - for example domestic abuse, child abuse, and the impact on mental health."

One interesting parallel that strikes him between our situation today and that faced by the three women who took part in the York Experiment (and in a second experiment the following year in which civil defence volunteer 'housewives' were challenged to buy a fortnight’s food for a family of four in half an hour at Jacksons in Bootham) was the consistency of the advice on food.

Government advice for surviving nuclear fallout in the 1960s always emphasised the need to stock up on non-perishable foodstuffs that would last at least 14 days, he says. That was also very much implied (though not specifically stated this time around. Those who have symptoms which they think may be coronavirus are asked to self-isolate for 14 days, he points out: which pretty much means they'll need enough food to last that long...

One thing that is different between now and the 1960s, however, is the role of local authorities, he says.

In the 1960s, there were strong civil defence organisations (a legacy of the war) which helped communities prepare - and which, in York's case, tested out the government advice.

Today, while councils like York have been involved in co-ordinating the efforts of volunteers, and have continued to carry out essential tasks such as collecting bins, they have not been involved in a major way in any strategic or regional effort to help us get through lockdown. It is almost as though central government doesn't trust local government to do the job, Dr Roodhouse says. A sign, perhaps, of how much more centralised the reins of power are today, despite talk of devolution...

If you were involved with or knew about The York Experiment in the 1960s, we'd love to hear from you. Call Stephen Lewis on 07880 059260.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel