WAY back in 1965, an eight-year-old Darlington boy was asked to write a school essay about what he wanted to be when he grew up.

Even then, the young John Oxley had no doubts.

"When I am 20 I hope to be an archaeologist," he wrote, in neat, looping handwriting.

More than half a century on - and after 30 years as the city archaeologist for York - the rather older John Oxley has no doubt that he made the right career choice.

He's loved being an archaeologist, he admits. It's different to being an historian.

Historians piece together the past by sifting through historical documents. But ordinary people seldom make their way into the pages of those documents, John says.

Archaeology, however, is all about ordinary people and everyday life, he says. As an archaeologist, you dig into the past with your own hands, and the objects you unearth are direct evidence about what the lives of ordinary people long dead were like - where they lived, what they ate and wore, what they made and traded. And that evidence is all just there, waiting to be found, waiting for you to interpret it and reconstruct those lives.

It is perhaps that storytelling that he loves as much as anything. "The objects don't talk. We have to make them talk," he says. "We have scientific techniques, a methodology that we use. But then we have to interpret the evidence to produce a narrative and tell a story."

Looking back, he still doesn't quite know where his passion for the past originally came from.

His dad was an office manager; his mum a secretary. No-one in his family had ever gone to university before.

But his mum loved history. "And we used to visit lots of historical sites," he says. "Perhaps that was it."

Whatever the reason, he pursued his chosen career doggedly. After school in Darlington, he went off to Liverpool to study ancient and medieval history and archaeology at university. His determination even survived a classic put-down in his very first archaeology lecture.

The lecturer walked in and glanced around at the group of 12 eager young students.

"And then he said: 'I hope none of you think you are going to get a job in archaeology, because there aren't any!'" John recalls.

John went on to prove him wrong. After finishing his undergraduate degree and a two year masters, he saw a job advertised in Southampton for an archaeologist to write up reports about past excavations in the city.

He was, by this time, a young married father. He needed to start earning. So he applied, and got the job.

He spent eight years in Southampton. It wasn't exactly hands-on archaeology, he admits. He rarely got the chance to go on digs, spending most of his time writing reports about excavations carried over the previous decade. But it was great training.

Then, in 1989, he saw a job advertised in York. He applied, and was successful.

The job title was 'principle archaeologist' - though in fact he was to be the only archaeologist employed directly by the city council.

It was a new post - and the young 33-year-old found himself walking, eyes wide open, onto a sticky wicket.

There had been a huge controversy in York. The city council had been pursuing an ambitious agenda of economic growth. It had identified 35 sites in the city for development - one of them the site of the former Queen's Hotel, on the corner of Micklegate and Skeldergate.

The listed Georgian coaching inn had been demolished some years before, in 1972. Since then, the site had stood vacant. The council gave planning permission for it to be redeveloped as an office block, and even gave approval for a basement four metres deep - catastrophic for any archaeology that lay beneath the surface.

The York Archaeological Trust had long since identified this as a site of real archaeological interest, John says - it was right where the old Roman civilian city had been. The Trust was given just over four months to investigate the site. But it didn't have the money to do a full-scale excavation - and by the time the developers moved in, it had not been able to finish.

Along with the Rose Theatre in London's Southwark, the Queen's Hotel case became a cause celebre, making the national headlines. It was partly because it was in York that it was so controversial, John admits. York, the city of Jorvik and the Coppergate dig, had been designated one of just five 'Areas of Archaeological Importance' in the country. "Archaeology was more important here. If mistakes were made, they mattered."

Perhaps partly as a result of the Rose Theatre and Queen's Hotel controversy, the government issued new planning guidance which gave local authorities the power to demand that developers contribute to the cost of archaeological investigations.

The city council in York also did two things to ensure there could not be a repeat of the Queen's Hotel fiasco: it commissioned a report by Arup and the University of York on the best procedure to adopt for developments on sites where there was likely to be important archaeology. And it appointed its own, in-house archaeologist to ensure that that procedure was followed.

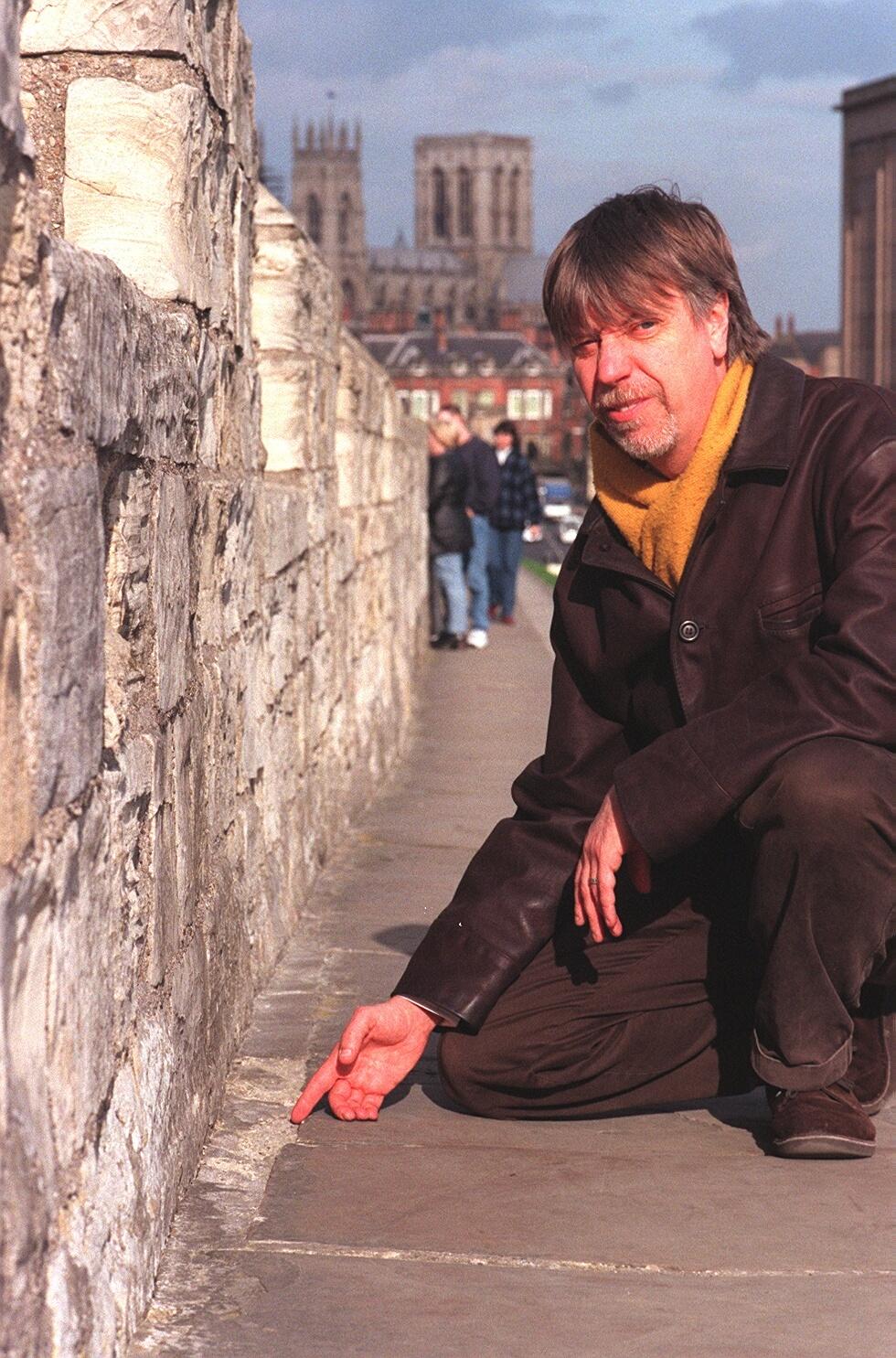

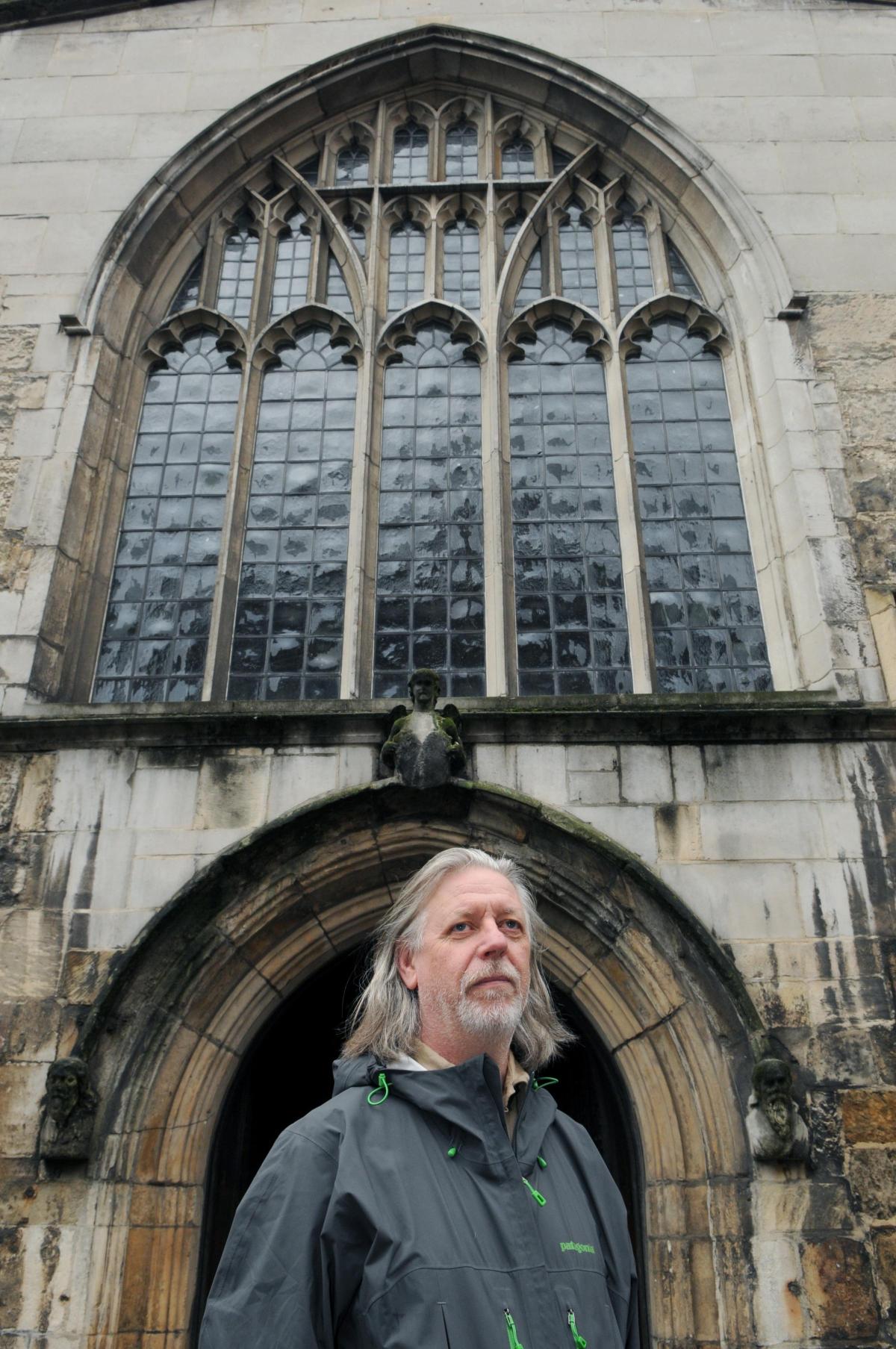

That archaeologist was John. He's been here ever since, his trademark white suit to be glimpsed clambering along the city walls or peering down into trenches, his long, pony-tailed hair getting gradually greyer as the years pass.

He likes to say that being the city archaeologist for York is the 'best job in archaeology in the country'. That’s not just because York archaeologists are the best (though they are, he says. People like Peter Addyman and the late Richard Hall of the York Archaeological Trust set the standard in urban archaeology for everybody else to follow. "Nobody does it better!") It's because there is so much brilliant archaeology here to delve into.

Admittedly, his job has been not so much about getting his own hands dirty, as about making sure other archaeologists in York get the chance to do so.

But even so, he's been here for some great digs, he says.

He has a few personal favourites.

The new campus at the University of York offered the chance to look at the archaeology on the east side of the city. And it revealed evidence that there were sophisticated peoples living here long before the Romans came 2,000 years ago, John says. Back then in the Iron Age, the area where York now stands was roughly on the border between the territories of two tribes - the Parisi to the east and the Brigantes to the north and south. Archaeologists found evidence of a landscape that was already farmed and cultivated. There were small settlements, probably for groups of extended families; areas of land that had been enclosed for crops; and others areas used as pasture for sheep and cattle.

Another of his favourite digs was at Hungate. There, archaeologists uncovered layers of history. Field patterns from Roman times; Roman burials; post-Roman agriculture; and, from the Viking period, plots of land with houses on and, behind them, evidence of some kind of industry.

What he particularly loved about the Hungate dig, however, was that it also focussed on more recent times - right up to the Victorians. Seebohm Rowntree, when compiling his great work on poverty, sent researchers into the Hungate slums to find out what their lives were like. Archaeologists were able to uncover traces of the Victorian houses.

The houses were demolished in the late 1930s, but there were still some York people who unremembered them, John says. "We even had one gent standing in the front room of the house he had last stood in in about 1939!"

His favourite find of all, however, came at Driffield Terrace. Between 2004-6, archaeologists unearthed the remains of no fewer than 86 Romans who had been buried there centuries ago. And they were astonished by one thing in particular.

"Every one had been decapitated!" John says.

Piecing together what had happened required archaeologists to use all their imagination and story-telling skills. But one favourite theory was that this might have been a gladiator's cemetery.

York's next major dig will be next summer, when archaeologists begin excavating beneath Rougier Street.

John will have retired by then - he officially steps down on December 31.

He will still be involved with York - he is one of those helping put together the city's latest bid for World Heritage Status.

But he's done his time, he says. If anyone had told him back in 1989 that he'd still be here 30 years layer, he'd have been astonished. "But I've loved it!"

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel