Review: A View From The Bridge, York Theatre Royal/Royal & Derngate Northampton, at York Theatre Royal, until October 12. Box office: 01904 623568 or at yorktheatreroyal.co.uk

LOOK at the climate in this country and across the world of the shifting antagonism towards immigration, particularly economic immigration, says York Theatre Royal associate director Juliet Forster.

She is highlighting the abiding relevance of Arthur Miller’s 1955 domestic drama, filtered through the prism of immigration being among the key trigger points for Brexiteer voters in the June 2016 Referendum. What’s more, she has picked a “mixed cast in terms of ethnicity and nationality” to further emphasise the resonance.

Miller’s setting is “the apartment and environment” of Red Hook longshoreman Eddie Carbone (Nicholas Karimi), assembled from a dockland shipping crate, whose cargo turns into the Carbone living room, against the backdrop of a metal framework that doubles as both staircases and the [Brooklyn] bridge of the title.

Everything drops into place in Rhys Jarman’s design, but Eddie loses his sense of his place in that home when extended family members Marco (Reuben Johnson) and younger brother Rodolpho (Pedro Leandro), illegal immigrants from Italy, are taken under the family wing.

Eddie’s body language is immediately confrontational, whereas his wife Beatrice (Laura Pyper) and especially17-year-old niece Catherine (Lili Miller in her professional stage debut) are more welcoming, especially to Rodolpho, with his distinctive blond hair and sweet singing voice. “There’s something not right about him,” says a fulminating Eddie, his masculinity challenged by Rodopho’s more exotic, fledgling, ambiguous air.

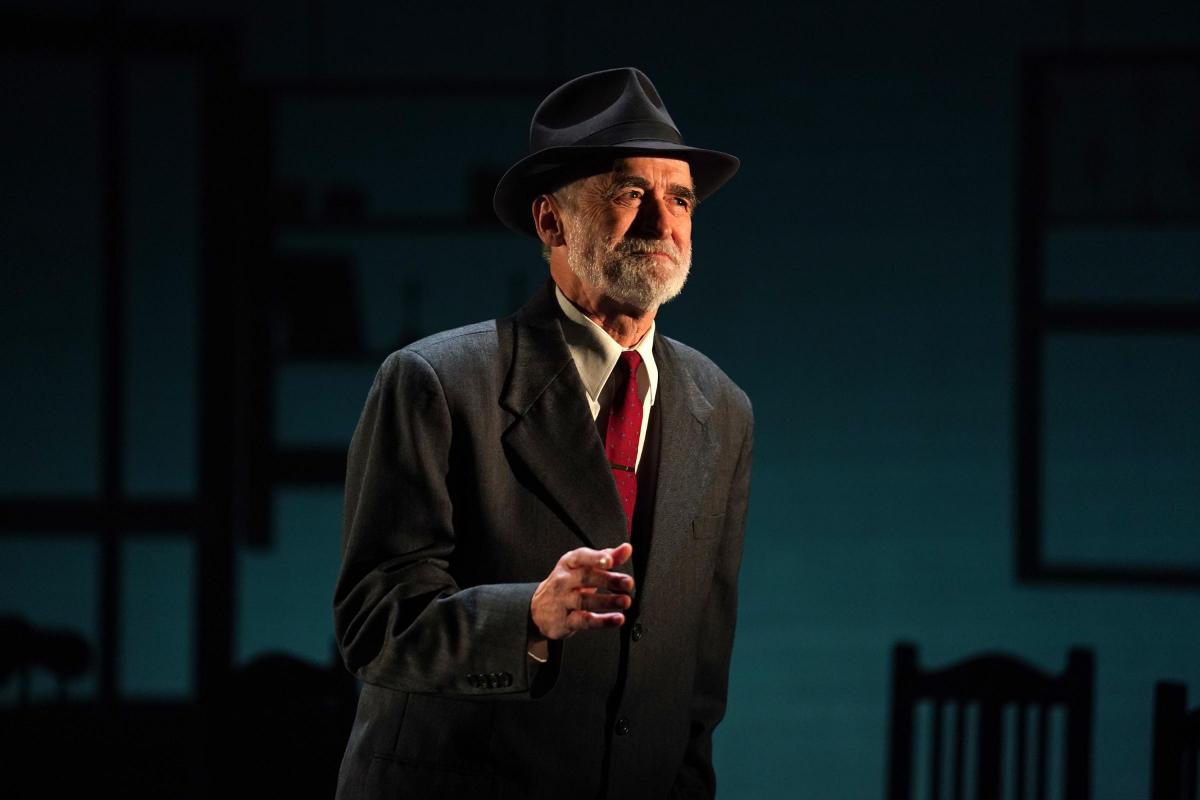

The titular “view” is that of venerable, urbane lawyer cum scene-setting narrator Alfieri (Robert Pickavance in his umpteenth role on a Yorkshire stage], who combines with the silent but omnipresent community ensemble to set the aforementioned environment, as well as forming Miller’s chorus for an epic drama that echoes the inexorable, inevitable downward tug of a Greek tragedy or Thomas Hardy novel.

Note that Miller calls it “A View”, not “The View”, because there is of course more than one view on agonised Eddie’s internal combustion: the vexed, law-abiding Alfieri; the volcanic Eddie; the Brooklyn American-Italian neighbourhood around him, such as his bowling buddies; Marco, whose sense of honour goes beyond the bounds of the law; Rodolpho, seeking his American Dream chance; and Beatrice and Catherine, each stepping out of dutiful compliance to Eddie to assert themselves.

Then there is Miller himself, the bridge that links everything in a play driven by his searing intelligence on a bumpy ride of emotional outpouring that exposes Eddie’s fault lines in particular, especially his desire for Catherine, who he has kept like a caged bird.

You may not find yourself agreeing with Alfieri’s view of admiring Eddie for being “purely himself, known wholly”, when in reality he is both controlling and unable to control his oppressive, obsessive feelings that stifle and destroy stifle others, while eating up himself to the point of self-destruction.

Aside from introducing the community chorus, Forster plays Miller’s play to the book, trusting in the intense, excellent central performances, the coruscating text, to bring out the troubling resonances for today, whether on immigration, masculinity or playing loose with the law and the truth.

She also does so by focusing almost wholly on the living room, not the steel walkway beyond, matching the confines of a boxing ring to notch up the suffocating intensity.

Miller’s work is loved by directors and actors alike, but inexplicably is a harder sell to audiences, especially in the provinces, to whom it should speak loudest. The tragedy would be to miss this play for today.

Charles Hutchinson

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel