Eighty years ago tomorrow, Britain declared war on Germany.

It had been coming for some time. Hitler's Germany was in an expansionist mood, occupying part of Czechoslovakia in 1938, the effectively taking over the rest in March 1939.

As the year wore on, it began eyeing up Poland. Britain and France both made promises to Poland that they would declare war on Germany if it invaded.

As that summer wore on, tensions continued to mount. In an editorial on July 20, 1939, the Yorkshire Evening Press had been both defiantly patriotic and resolutely optimistic. The ranks of the Territorial Army had swelled to twice the size in just three weeks, it noted. "It can be seen that, week by week, the wall of national defence is rising stronger and higher," it declared. "No aggressor will dare raise his head."

Sadly, Hitler didn't seem to be paying attention. The tensions continued to rise, and as war drew closer, the language in the Yorkshire Evening Press became more sombre. "In these grave hours, the need for unity is greatest," it declared, in an editorial on August 26. "There must be no foolish talk, no stupid bandying about of rumours... Cheerfulness and confidence must rule our conduct."

It didn't make any difference. Germany invaded Poland on September 1 in search of more 'living space'. Britain and France gave Hitler a deadline of 11am on September 3 to pull his forced back from Poland. When he failed to do so, we were officially at war.

"This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o'clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us," Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain said in a speech delivered from the Cabinet Room at No 10.

"I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany."

There was no immediate panic - and in fact, for most British people at least, the declaration of war at first made little difference. The first eight months of the war became known as the 'phony war', because so little happened. "Was there ever less fuss about a declaration of war than we saw last Sunday morning?", the weekly Yorkshire Gazette asked in an editorial on September 8.

Nevertheless, in York, the authorities began to take steps to protect the population, according to historian David Rubinstein in his book York In War And Peace. All 64 of the local education committee's schools in York were closed so that they could be fitted with shelters or other protection for children and staff. York's Air Raid Precautions (ARP) committee, meanwhile, ordered 680 public shelters to be built across the city, and the job of recruiting and training hundreds of volunteer air raid wardens began.

Volunteers were told that they would be compensated for the time they spent away from their jobs on ARP duty - but even so, to begin with, there was large scale public indifference. There were more spectators than volunteers at the first ARP exercise, the Yorkshire Gazette noted tartly. By October 17, 1700 men and women had registered as ARP volunteers - though 500 of these never turned up for duty, and of the rest, fewer than 1,000 were judged to be effective, the minutes of the ARP Emergency committee recorded.

Nevertheless, York was gradually getting itself onto a war footing. Blackouts became a daily occurrence, and on May 10, 1940, when Germany invaded France and the Low Countries, the 'phony' war suddenly turned frighteningly real. Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain were to follow - and, here on the home front in York, more blackouts, rationing, those dreadful telegrams informing families of the death of a loved one - and, one night in April 1942, the York Blitz.

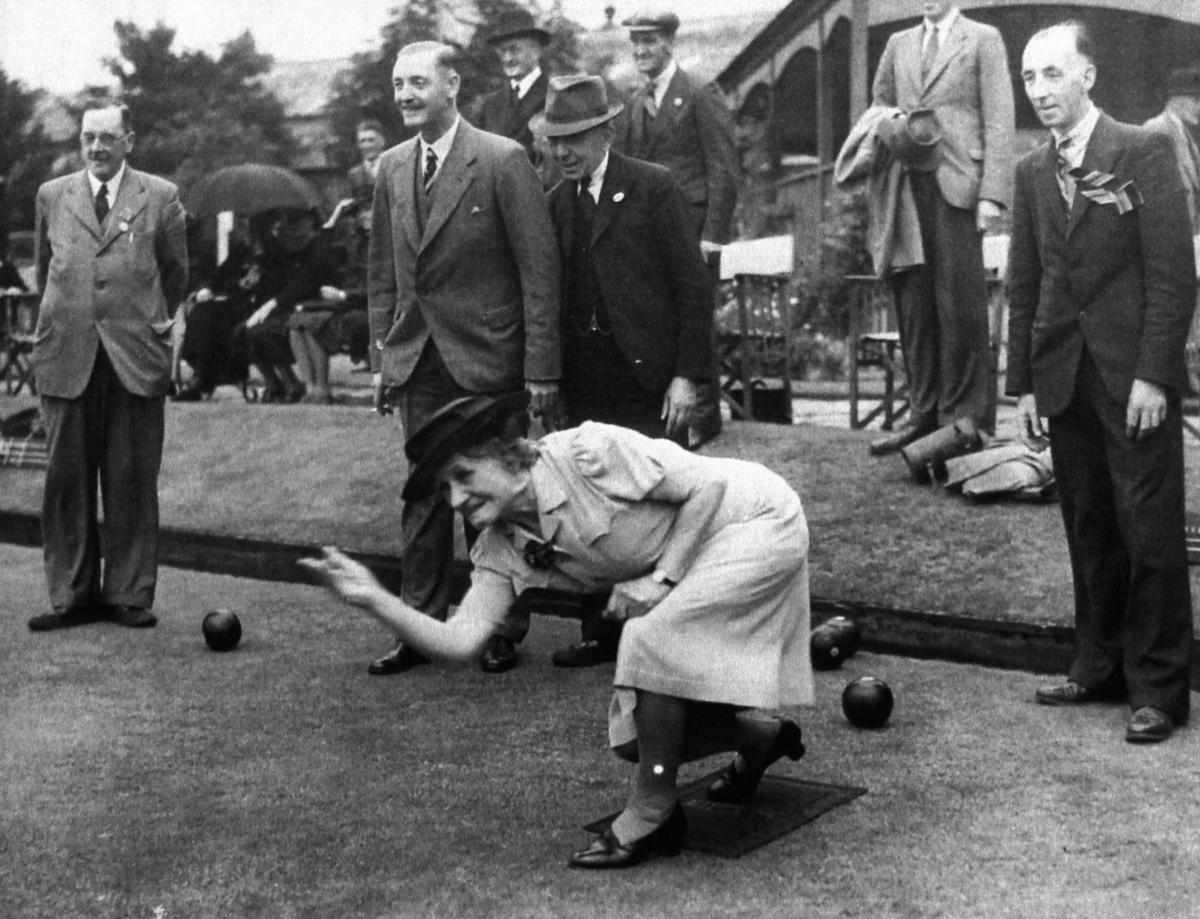

We have a limited archive of photographs of York during the Second World War here at The Press. Many feature the aftermath of the Blitz: those we'll save form another time. The selection of pictures we have chosen today try to give instead a sense of life continuing in York in the teeth of the war: the women volunteering as WAAFs, the boys training as cadets, soldiers and civilians rubbing shoulders in Coney Street - and even wartime Lord Mayor Edna Annie Crichton enjoying a game of bowls, as cool as Sir Francis Drake at the approach of the Spanish Armada...

Stephen Lewis

BLOB

York Civic Trust and Explore York Libraries and Archives have just produced a new educational workpack for local primary schools called York In The Second World War. The pack will be going out to all local primary schools in the next couple of weeks, and will also be available to view or download from the York Civic Trust website www.yorkcivictruist.co.uk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here