WHAT do you do if you're a fifth-year medical student offered a chance to do a learning placement in the Seychelles?

You jump at the chance, of course.

Which is just what Yorkshire student Molly Nichols did.

Not that Molly, who was just coming to the end of her fifth year of a medicine degree at Oxford, dreamed of spending her evenings relaxing on palm-fringed beaches gazing out over the Indian Ocean, of course.

This was to be a work placement. And there were solid reasons for choosing the Seychelles, an archipelago of more than 100 islands in the Indian ocean off the east coast of Africa.

The idea of the 'overseas placement' is to learn about how healthcare is managed in other countries, explains Molly, 23.

Other Oxford medical students had been to the Seychelles in previous years, and highly recommended it. "Many of the locals are bilingual, speaking English as well as Creole. So consultations are easy to follow and patients are able to understand our interactions with the doctor," says Molly. She'd also be able to talk to patients herself, and take down their case histories.

But she admits she was also intrigued to see the Seychelles themselves. The archipelago is well known as a holiday destination for the well-heeled. "So we thought it would be interesting to gain more of an insight into what life is like away from the beaches.”

She flew out to the archipelago earlier this year with three other Oxford medical students: Isobel Tol, Aditi Aggarwal and Willow Fox.

There's only one main hospital in the archipelago, in the capital city of Victoria on the main island of Mahe, she says. Smaller islands have health centres and clinics. "But if more complex care is needed, people come by plane or ferry to Mahe," Molly says.

Pregnant women, in particular, often travel to the main island to give birth in hospital. Molly was on a women’s health placement and was based in the obstretrics and gynaecology department.

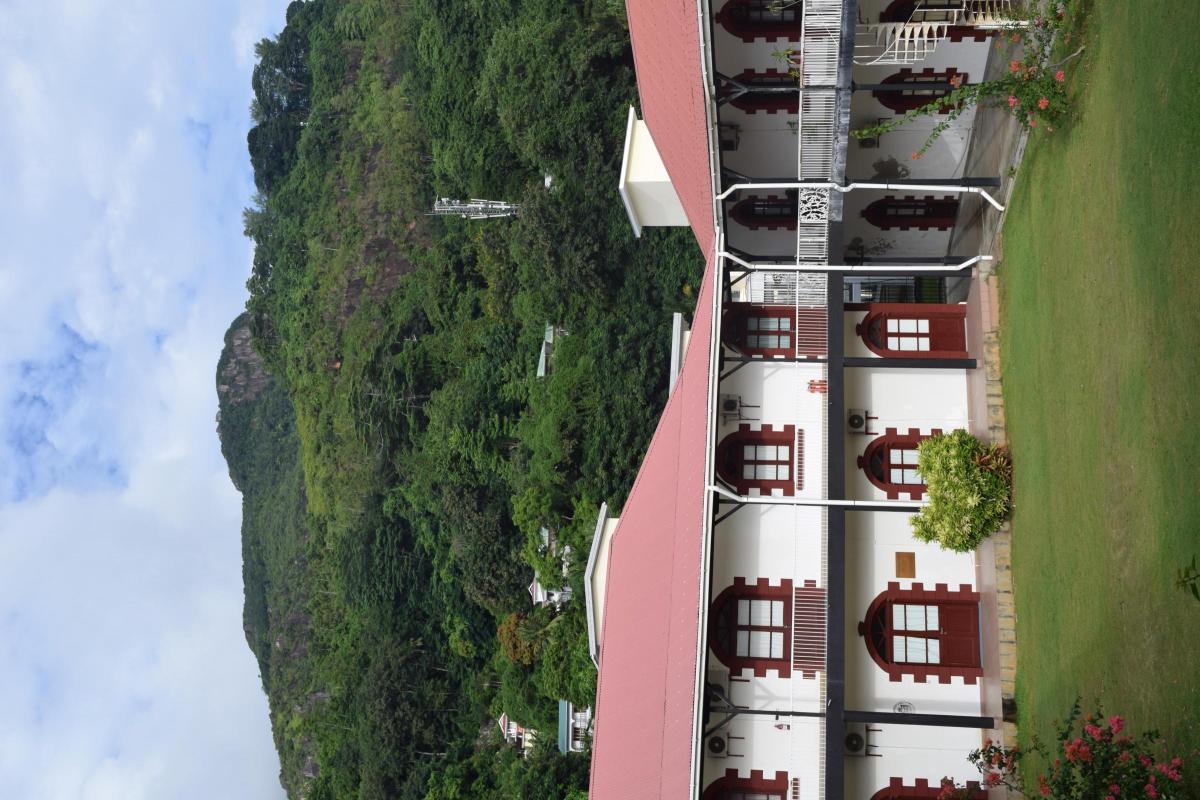

The hospital itself was a big, colonial-style building with more modern, 1960s-style extensions. And she was generally impressed with what she saw.

Like in the UK, healthcare is free in the Seychelles - within limits."Being a small island which relies heavily on imports, some treatments which are deemed non-essential and costly must be self-funded by the patient," she says. "I was told by a doctor, for example, that the patient must pay for an epidural during labour if it was not strictly, medically indicated."

There were also certain operations that couldn't be carried out in the Seychelles. When that happened, patients would often have to travel to India, Molly says. "The hospital in Victoria has strong historic links with hospitals in India - there has always been a relatively large Indian community on the island."

There are, in fact, close links between the Seychelles and India, she says. "As well as providing a large amount of medical equipment, India donated a number of buses to the island to allow for cheap public transport.”

Despite its limitations, however, the hospital was bigger and better equipped than she had expected, if a few years behind the UK. Wards had proper hospital beds and nursing stations, although they were more crowded than in a UK hospital. "Some of the buildings were more rundown than they are here, lacking air conditioning or having damp on the walls. But their operating theatres were sterile spaces and had equipment for keyhole surgery."

She and her fellow students were able to sit in on clinics, accompany doctors on ward rounds, and observe deliveries and theatre sessions.

“I watched doctors carry our hysterectomies and C-sections. We were able to examine women and give treatment advice to patients."

She quickly realised that doctors in the Seychelles are held in great respect. They saw a lot of patients, and had little time to spend with each one - often racing through a consultation in five minutes or so. And their approach to consultations was different to UK doctors. "They tended to be a bit more traditional, a little more blunt and to the point with diagnoses," Molly says. "There seemed to be less in the way of counselling for treatment options and test results."

Nevertheless, patients seemed to have more trust in their doctors' decisions than do patients in the UK, she says - and expected and demanded less of them.

“In the UK, I feel that patients have started taking matters into their own hands, researching possible conditions and treatment options in advance of their consultation. There is a definite difference in patient expectations between Mahe and the UK.”

Away from the hospital, she was surprised by the relatively high standard of living.

Yes, she admits, there was a huge difference between the tourist enclaves with their yachts and exclusive five-star resorts and the lives led by ordinary Seychellois. Most people lived in simple one- or two-storey brick buildings, with balconies and tiled roofs.

For all its idyllic reputation, the Seychelles has a problem with drugs: especially heroin. It is cheap and plentiful, Molly says: possibly because of the islands' location on the trade routes. Opiates are routinely prescribed for pain relief - and heroin is the recreational drug of choice. Many mothers are heroin users - and that means many babies are born addicted to the drug.

Addict mothers were routinely given replacement drugs, she says. And their babies, which tended to be born quite small, were often kept in the hospital's neonatal unit for a while. "They are given drugs which help with the side effects of the withdrawal," says Molly.

She's not the first to have noticed the archipelago's drugs problem, of course. A British government travel advisory issued in May this year notes: "There is a problem with drugs in Seychelles, in particular heroin. Crime levels have risen as a result."

Molly never got to experience any crime - but she did get at least a glimpse of the darker side of the Seychelles.

One evening, one of the mothers who was an addict, and whose baby was being looked after at the hospital, offered to accompany Molly and her friends on their way back to their lodgings. They took a route through an area which was clearly a drugs hotspot. "We saw drug users standing by the path with all their paraphernalia," Molly says.

Molly never felt threatened herself, however. And drugs problems apart, she says living standards on the islands appeared to be reasonably good.

She was surprised by how high prices of things like basic groceries were. "Groceries were more expensive than in London - reliance on imports has been thought to push prices up. But I believe the standard of living is quite high despite everything being costly."

The locals were always very friendly. And she had few problems making herself understood.

Historically, the islands were colonised by both the French and the British. "The main languages spoken are Creole, English and French. It is interesting, when listening to local people, to hear how they mix all three languages in day to day chatter. It was not uncommon to hear locals switching between languages mid-sentence.”

And then, of course, there were those beaches.

Prices for tourists are very steep. But Molly and her friends were able to use their work permits to visit some of the local islands by ferry at discounted rates. They were even able to rent a car to explore.

“It is a beautiful landscape with lush vegetation, beautiful coastal and rock formations and high mountains, with islands on the horizon. The ocean is crystal clear, with varying shades of blue, and crisp white sands," she says.

Best of all, perhaps - there was no McDonald’s or Starbucks, and very little litter. "The local people are very environmentally conscious.”

We could perhaps learn a thing or two from them...

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here