Wanted: people willing to play 'mind games'. Download a free app and you could help researchers find a way to train our brains so our memory stays better as we get older, says STEPHEN LEWIS

I'VE always thought I have a pretty good memory. After all, more than 30 years ago, I passed the 100-words-a-minute shorthand test all journalists have to take mainly because my memory was good. My shorthand was slow, but I just kept writing long after the examiner had finished dictating, calmly listening to her voice unspool like a tape player inside my head.

But that was then. How would I cope if my memory was put to the test today?

Not as well as I thought I would, is the answer.

The York Memory Mind Game is a fiendish little app you can download on your mobile phone or tablet.

It is designed to test not only how good your short-term memory is - but also how well you can cope with distractions.

A series of red circles appear briefly on a gridded screen, then vanish. Once they have gone, you have to tap the screen to indicate where they were. Get it right, and you're rewarded with a big green tick. Get it wrong, and you get a red cross.

To complicate things, a series of yellow circles are flashed up, too. Sometimes these appear at the same time as the red circles: sometimes shortly after they have gone. You're supposed to ignore the yellow circles, and remember only where the red circles appeared.

Sounds easy enough, yes? And so it was ... at first.

There were just three or four red circles to begin with. Once they disappeared, I could almost see in my mind's eye the imprint of where they had been on the screen, and had no difficulty tapping out the correct answer.

Then some yellow circles began appearing, too. At first, I had no difficulty ignoring these. But then the number of circles, both red and yellow, began to increase - and they seemed to appear at different times. Suddenly, I began to make mistakes. And even if I got only a single circle wrong, I still got that ugly red cross instead of the green tick.

Mind Games: playing the game

Game over, I turned to University of York psychologist Dr Fiona McNab. So how did I do? I asked.

She consulted the data that had been fed through from my phone onto her screen, then gave a little nod. "You got 70 per cent," she said.

Better than I thought. But I immediately wanted to play again, to improve on my score. Which is exactly what Dr McNab and her colleagues want...

The York Memory Games have been developed with the help of a grant from The Welcome Trust to look at the way our short-term memory changes with age. Specifically, researchers are interested in our ability to ignore distractions while trying to remember something.

The amount of information we can hold in our mind for a short time (what we call our short term memory) is limited. There is clear evidence that, as we get older, our short term memory generally gets worse - even if we're perfectly healthy. There's also evidence that our ability to ignore distractions gets worse as we get older - and that this affects our ability to remember things.

Dr McNab gives an example. You're about to make a phone call but don't have the number. You call across the office to see if anyone else has it, and a colleague calls back to give you the number. Then, just as you're about to dial it, a dog starts barking outside the open window. Does this distraction put you off, or can you still dial the number correctly?

The evidence shows that, as we get older, our ability to ignore distractions like that and remember the number so that we can still dial correctly falls off sharply.

Dr McNab and her colleagues are studying how and why that happens - which is why they need thousands of people of all ages willing to play her 'mind games'.

Dr Fiona McNab

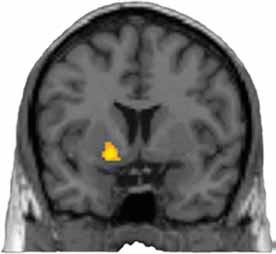

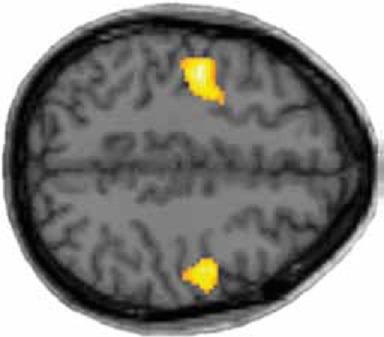

Brain scans of people playing similar mind games have already revealed that there are certain regions of the brain involved in the process of 'filtering out' distractions. "And these age at different rates," Dr McNab says.

That might help to explain why our ability to ignore distractions while trying to commit things to memory gets so much worse as we get older.

But there's also evidence that, as we get older, we try to compensate for this, Dr McNab says. "The speculation is that older people may be using different parts of their brain to remember, to try to compensate for their increasing difficulty in ignoring distractions."

If this is so, and if researchers can understand better how that works, it could help experts develop brain-training techniques that we can all use as we get older to counter the gradual loss of our short-term memory.

And that could make a real difference to the quality of life of otherwise healthy older people, Dr McNab says.

We need our short-term memory to do all kinds of things in our daily lives, she says - doing the shopping, keeping track of our finances, even holding a conversation.

"So if we can help otherwise healthy older people retain their short-term memory, that would really contribute to their quality of life, and would help them to keep on living independently."

That's where you come in. Dr McNab and her colleagues need thousands of people to play her 'mind games' so that they can analyse the data and use it to work out just what is going on when we try to memorise things while we're being distracted. They also want people to play the games again and again (hence the importance of making us want to 'better our own score). They will be able to use that data to help understand how practice can improve our memory, and our ability to ignore distraction.

Crucially, however, they also want people of all ages - from five up to 75 and above - to play. That way, they really can begin to get a clearer idea of just how our brains' ability to remember and filter out distractions changes with age - and whether there are any strategies that can be taught to help us improve out short term memories as we get older.

So if you want to give your brain a workout, have fun, and help in a research project that could help us develop strategies for remembering better as we get older, you know what to do...

HOW TO TAKE PART

To take part in the York Memory Games project, download the free app here: www.york.ac.uk/psychology/research/areas/cognition-communication/yormega/

There are a range of games to choose from: you can choose to play however many you want.

As you play, your results will be fed into a database kept by Dr McNab. The data gathered will be anonymous: you won't be asked for your name and no-one is interested in trying to sell you anything, or in predicting your shopping habits. But you will be asked if you are willing to include your date of birth. This is because the project is looking at how our memory changes with age. Giving your date of birth will be optional, Dr McNab says. "But we'll only be able to use your results if you do so." The game explains what researchers will do with the data they collect, Dr McNab adds. "We hope people will share the games with their friends and family. We need as many players as possible!"

Dr McNab and her team are also looking for volunteers who would be willing to have their brains scanned while playing memory games, so as to learn more about which parts of the brain are involved in specific memory tasks. Volunteers should email fiona.mcnab@york.ac.uk

THE SCIENCE OF MIND GAMES

The aim of the York Memory Games project is for scientists to better understand exactly what happens when we commit information into our short term memory - and how this process changes as we get older.

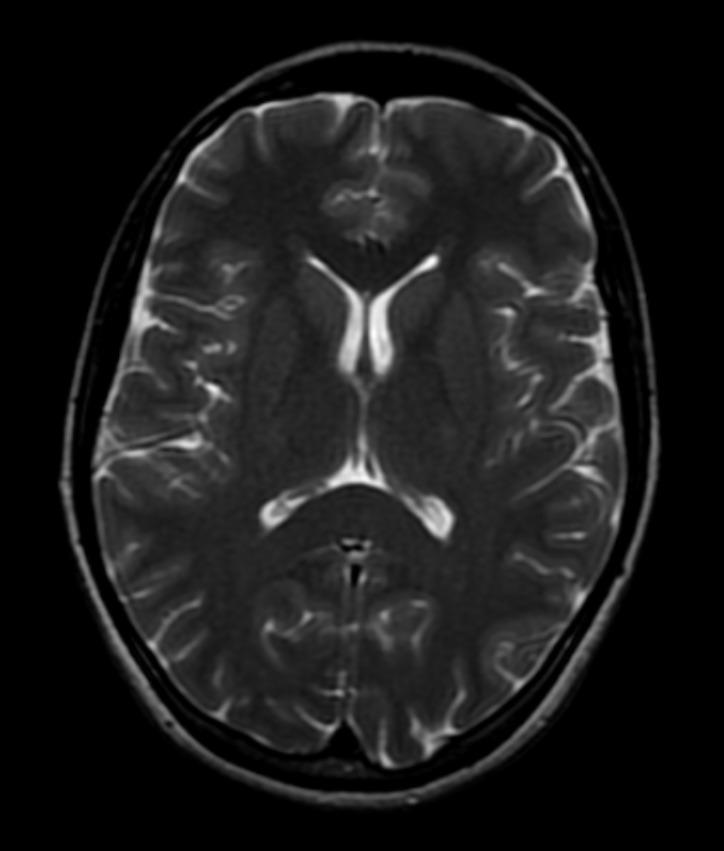

A scan of the brain with areas associated with short term memory highlighted

As we get older, we find it harder to filter out distractions. This seems to affect our ability to commit things to memory when there is a distraction, such as an overheard noise. A distraction that occurs very shortly after we've committed something to memory and are about to start using the information we have just memorised is particularly difficult for older people to deal with.

Studies involving brain scans suggest that certain key areas of the brain are involved in helping us to 'filter out' distractions so we can focus on remembering only what is relevant. But different parts of the brain age at different rates - which may be why we find it more difficult to filter out distractions as we get older, Dr McNab says.

There is evidence that some people start to 'compensate' for this as they get older, by using different parts of their brain to store information and to screen out distractions. If we can better understand this mechanism, and get more information about the range of ways in which different people do this, it may help in the development of brain-training strategies that can help us retain a good short-term memory into older age.

The research is not aimed at finding ways to help people with Alzheimer's Disease or other forms of dementia. But it could lead to coping strategies that enable healthy older people keep their memory better in older age.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here