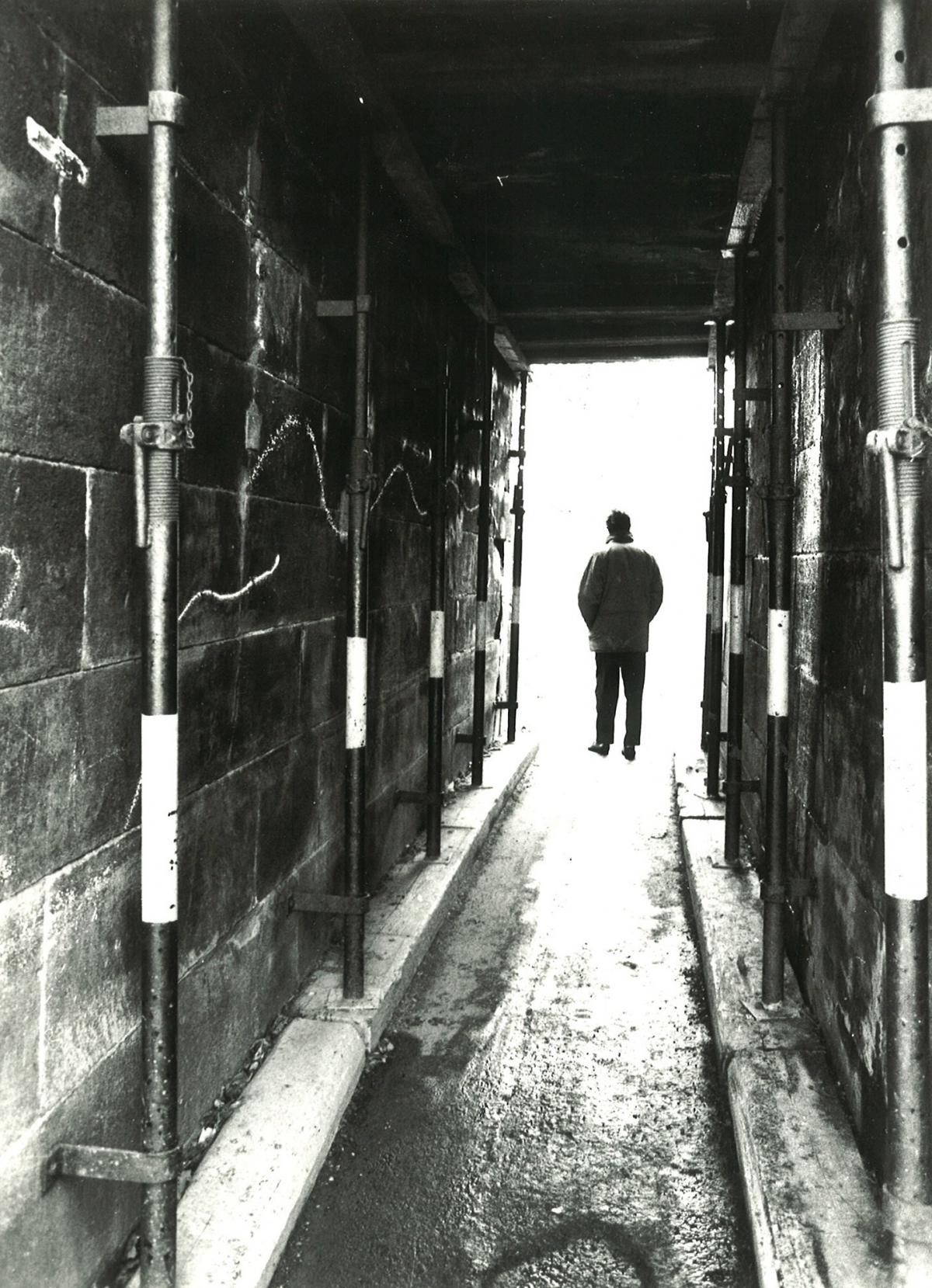

No-one who lives or works in Clifton or Bootham can have failed to notice that for some time, Scarborough Bridge has been closed to pedestrians. The walkway has been shut since January, in fact, as part of Network Rail's programme to improve access for pedestrians and cyclists. This has involved replacing the old walkway with one which will be nearly three times as wide. The closure has forced three thousand daily users to find alternative routes across the River Ouse.

Not for much longer, fortunately. The bridge's walkway is due to re-open to pedestrians and cyclists on Thursday. So now seems a good time to take a look back at the bridge's history.

Scarborough Bridge was first built in 1845 to serve the York & North Midland Railway line to Scarborough. In its original incarnation, it provided a pedestrian footway sandwiched between the bridge's two railway tracks, offering Victorian citizens a second option for crossing the Ouse by foot in addition to Ouse Bridge.

The Scarborough Bridge walkway must have been a godsend, even if the experience of walking along a sunken footway between moving locomotives would surely have been terrifying. The introduction of a pedestrian pathway on the eastern side of the bridge in 1873-75 must have been very welcome.

In 1911, however, there was a shocking incident that could easily have led to a catastrophic loss of life.

On the afternoon of Friday April 18, 1911, there was an alleged attempt to wreck a passenger train near Scarborough Bridge in what York’s stationmaster described at the time as a 'cowardly and dastardly act'. The 5 o’clock evening train to Scarborough had just set off from York Station when it was pulled up with a sudden jerk before the points at Scarborough Bridge.

Catastrophe was averted by the quick actions of a signalman, who on realising that the levers to change the track points to the bridge were not working correctly telephoned the stationmaster’s office and warned the train driver to stop in the nick of time. It was soon found that the points' failure was due to stones and a large piece of coal the size of a brick having been wedged in.

A train derailing here, even at low speed, could have easily tumbled over the side of Scarborough Bridge and into the river below, leading to death and destruction. That men were seen on the parapets of Scarborough Bridge, only clearing off when officials arrived on the scene, suggests it was no accident.

What could compel men to act so recklessly? The answer lies in the social and political conditions of the years immediately before the First World War. It is tempting to imagine these years through the lens of TV dramas like Downton Abbey: summer fetes and a social class system in which everyone merrily knew their place. The reality was more challenging. Historians call the 1910-14 period ‘The Great Unrest’. Irish Home Rule (devolution in another name) presented an unresolvable constitutional crisis, while diminishing wages brought economic hardship for many in a society sharply divided by class. Parallels with our current era are easy to spot.

It was these social problems that led to the near-tragedy at Scarborough Bridge in 1911. The railway trade unions had been threatening to call a general transport strike since 1907. They wanted collective bargaining for better wages and safer working conditions for their members.

The first ever National Railway Strike was called on August 17, 1911. While Liverpool was the epicentre, incidents followed across the country. In total 200,000 workers were involved in strike action before greater union recognition and a Royal Commission to investigate conditions and industrial relations ended the strike after three days.

Since York was a major junction on the railway network, there were other major incidents in the city during the strike in addition to that at Scarborough Bridge.

On the first evening of the strike, passing trains were pelted with bricks and stones by strikers from their position on the then recently opened Iron Bridge in Holgate. The 8.15pm express from King’s Cross suffered considerable damage, with carriage windows smashed and the engine driver struck and injured. Passengers were understandably terrified. Further stones were thrown at trains from the bridge on the Sunday evening, until the army intervened.

In another incident, it was found that strikers had tampered with a level-crossing gate mechanism on the York to Scarborough line. The 10 o’clock train from Scarborough to York, and 10.30pm train going the other way, were forced to stand facing one another for several hours, either side of gates at Burton Lane junction, near Crichton Avenue.

Elsewhere, the military broke up disturbances by strikers at Poppleton, and had to retake possession of the Naburn Bridge signal box.

The 1911 strike also led to the State flexing its muscles. The Prime minster, Herbert Asquith, declared that the government would ‘use all the civil and military forces at its disposal’ to ensure that trains continued to run. His Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, deployed 58,000 troops across key points, as well as sending the cruiser HMS Antrim to take position in the Mersey.

Following the Scarborough Bridge incident, nearly 200 troops from the York & Lancaster Regiment were dispatched to protect York's main railway station, the engine shed on Leeman Road and various key rail locations. En route from the barracks, the soldiers collected the Lord Mayor, Alderman Thomas Carter, in case he needed to literally read the ‘Riot Act’ to strikers. In subsequent days, some 500 troops were on duty at the station.

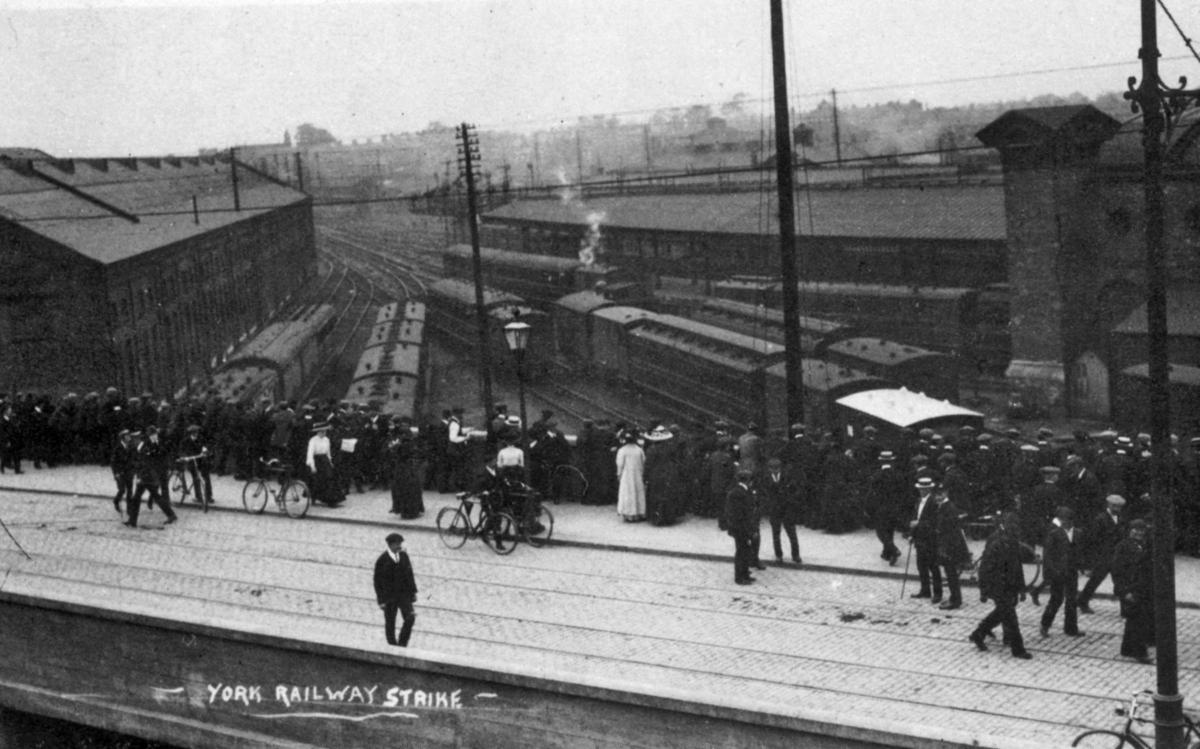

According to newspaper accounts, however, soldiers could be found socialising with the large crowds that came and stood on the Queen Street Bridge and at Station Road to observe the strike. Thanks to York historian Paul Chrystal's book Yorkshire's Days of Steam, we actually have a photo of strikers and spectators mingling on the bridge. It's a wonderful moment of York history preserved.

Duncan Marks

Duncan Marks works for York Civic Trust

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here