STEPHEN LEWIS delves into a treasure trove of architects' drawings and engineers' plans that reveal a York that was never built

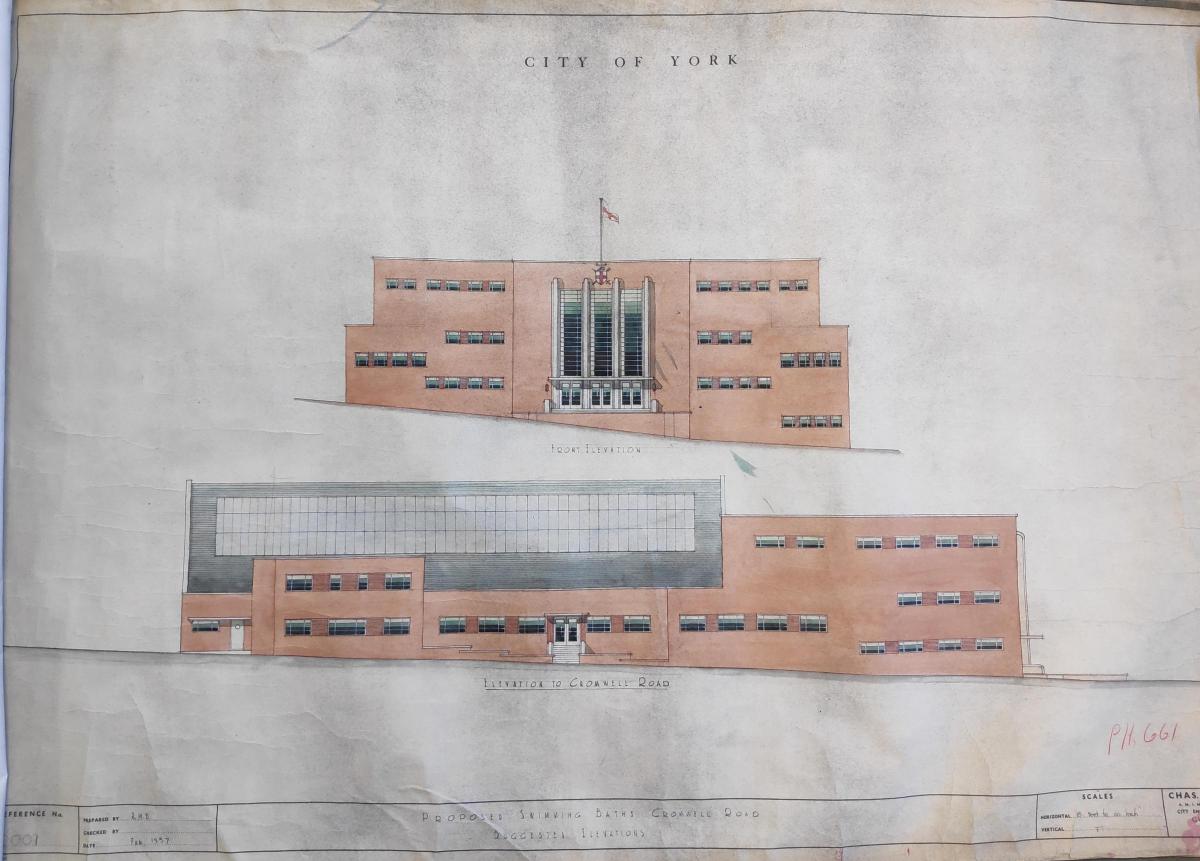

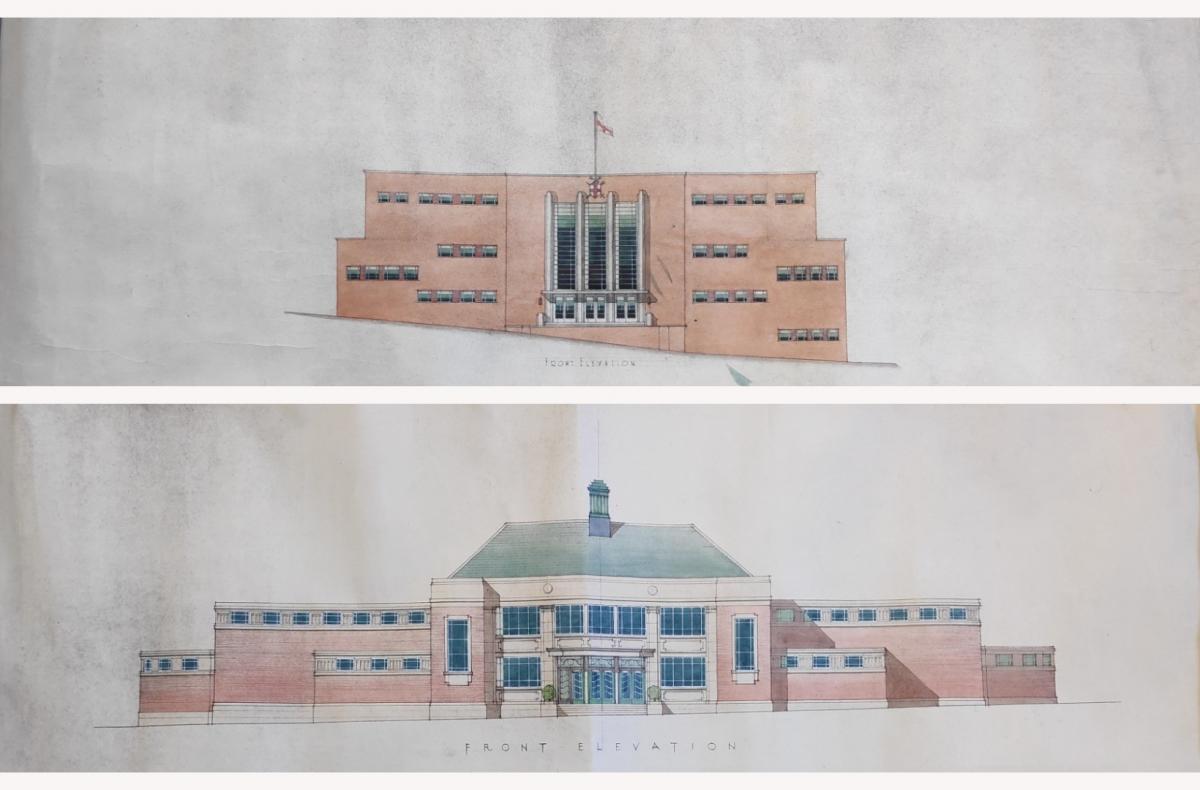

YOU will never have been to the stunning art deco municipal baths in Cromwell Road, nor to the equally impressive ones in Hungate. The fact that they never got built may have a bit to do with that.

But what a shame that is. Architects plans and drawings uncovered by archivists at Explore York show that the city council of the day didn't plan to stint on the new buildings.

The plans show impressive art deco interiors; curved, high-arching glass ceilings; large pools; generous changing areas; and - at the Cromwell Road baths, at least - a roof garden, and separate slipper baths and zotofoam baths.

Zotofoam baths? "It was an early form of jacuzzi promoted as a way of losing weight for women," says archivist Julie-Ann Vickers. "Swimming was a bit of a health craze at the time."

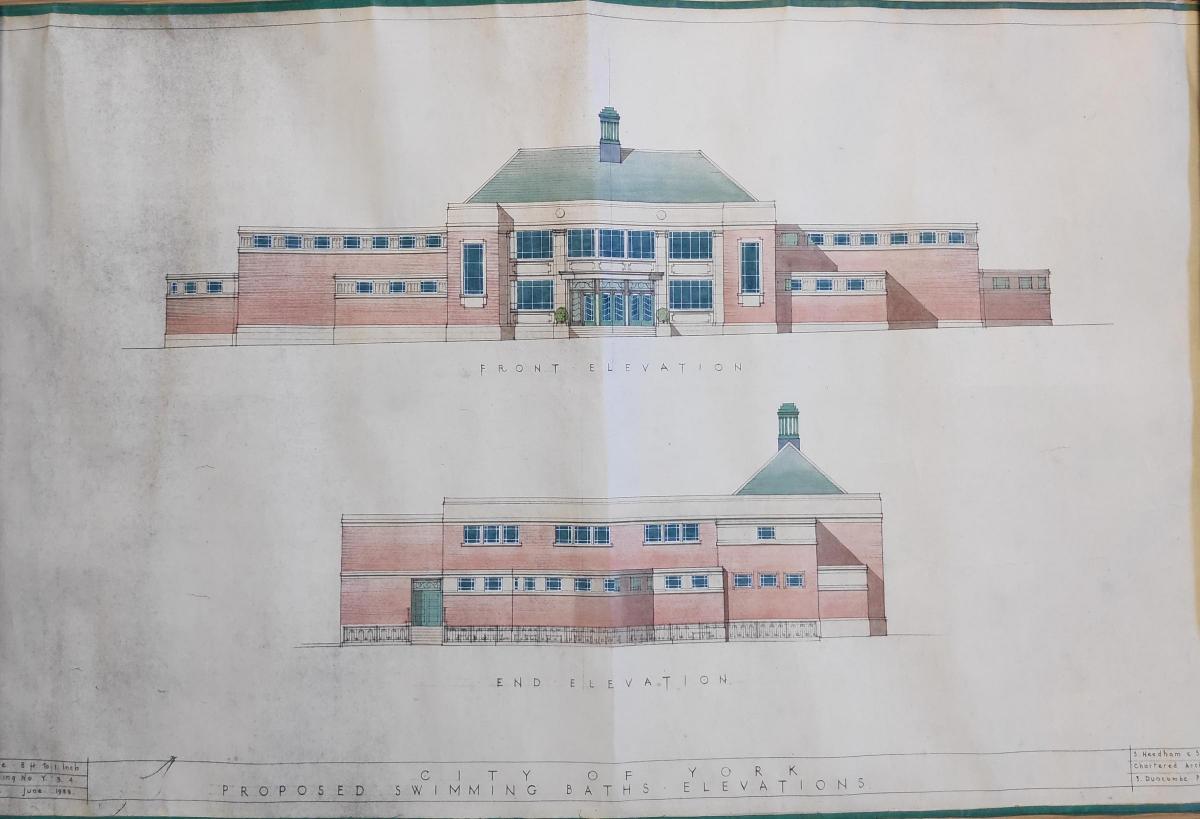

Drawing of the proposed Hungate baths

Neither the Cromwell Road nor the Hungate baths ever got built, sadly. The latest drawings date from May 1939, and after that they're not mentioned again. The Second World War got in the way - and once the war was over, presumably such expansive public projects were simply impossible in the post-war austerity years.

The architects' drawings left behind are themselves things of beauty, however. We can only imagine what the buildings themselves would have been like: particularly since York, for all its heritage, has very little in the way of art-deco civic buildings from the 1920s and 30s.

The drawings are among tens of thousands of documents, plans and drawings from the city architects' and engineers' department that are now being carefully catalogued by archivists, with the help of a small army of volunteers.

The documents date from the 1830s right up to the 1990s, and they cover a whole range of civic and municipal projects, from street widening to sewers and public conveniences; grand civic buildings such as the York Fine Art and Industrial Exhibition hall (today's art gallery) to civic housing.

Archivists have already begun categorising the plans and drawings into three broad types, Julie-Ann admits.

"There are plans for buildings that were built, but now no longer exist; buildings that were built and that we still have today; and a York that never was - buildings that were proposed but that never happened."

It is those last that really catch at the imagination - buildings that were planned for, but which for whatever reason never came off. Finding out about them allows us to play the game of imagining how different York could have been.

A plan of the Cromwell Road baths

The two municipal swimming baths that York never got are classic examples of this category. But the archivists and their team of volunteers have really only just begun the process of cataloguing. Who knows what other abandond or forgotten public projects they will uncover between now and the end of the year?

The On The Drawing Board project has been made possible thanks to funding from the Archives Revealed grant programme and from the city council.

Archivists and their team of volunteers began the process of investigating and cataloguing the thousands of documents last October. The work will continue to the end of December, with the aim ultimately of making these documents accessible to the public at the Explore York archives reading room on the first floor of the central library.

There are also plans for an open day at the library, perhaps in November, so that archivists can show off some of the best of the plans.

At the moment, apart from the plans that have already been catalogued, they have little idea about what they might yet discover.

Volunteers Thomas Chisholm and Rachel Kirke study some of the plans. Photo: Stephen Lewis

Before the new archive facility at the central library opened in 2015, the architects' and engineers' collection was kept in storage at the side of York Art Gallery.

Nobody really knew what was there. The plans and drawings were all in tight rolls, many of which hadn't been opened and looked at for decades.

When the art gallery was redeveloped, the plans were transferred to 'deep storage' - but again, without anyone looking at them. Each roll was simply wrapped in special protective paper.

Now, painstakingly, the archivists and their volunteers are unwrapping each of those rolls one by one - cataloguing and describing the contents as they go.

It's an exciting process. Some of the plans and drawings may have been looked at as recently as the 1970s, says Julie-Ann. "But others haven't been looked at since they were put into a pigeonhole in Victorian times."

When I joined the archivists for a morning, volunteer John Carlill was about to open a new roll. We craned around to watch.

He gradually opened the roll out - to reveal a sheaf of street plans from the 1880s. They seemed to relate to the widening of Duncombe Place - and in particular, to detail some minor alterations to the building on the corner of Blake Street and Duncombe Place.

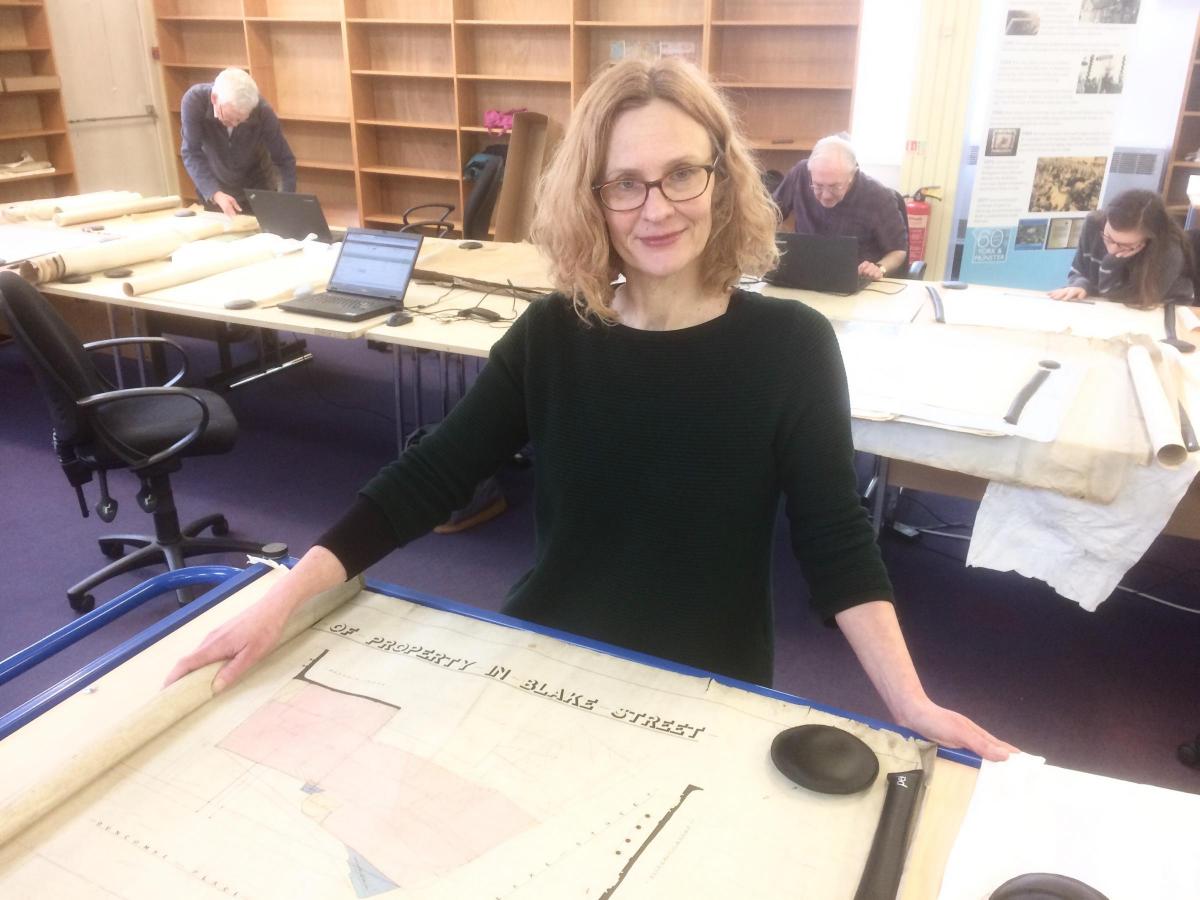

Archivist Julie-Ann Vickers

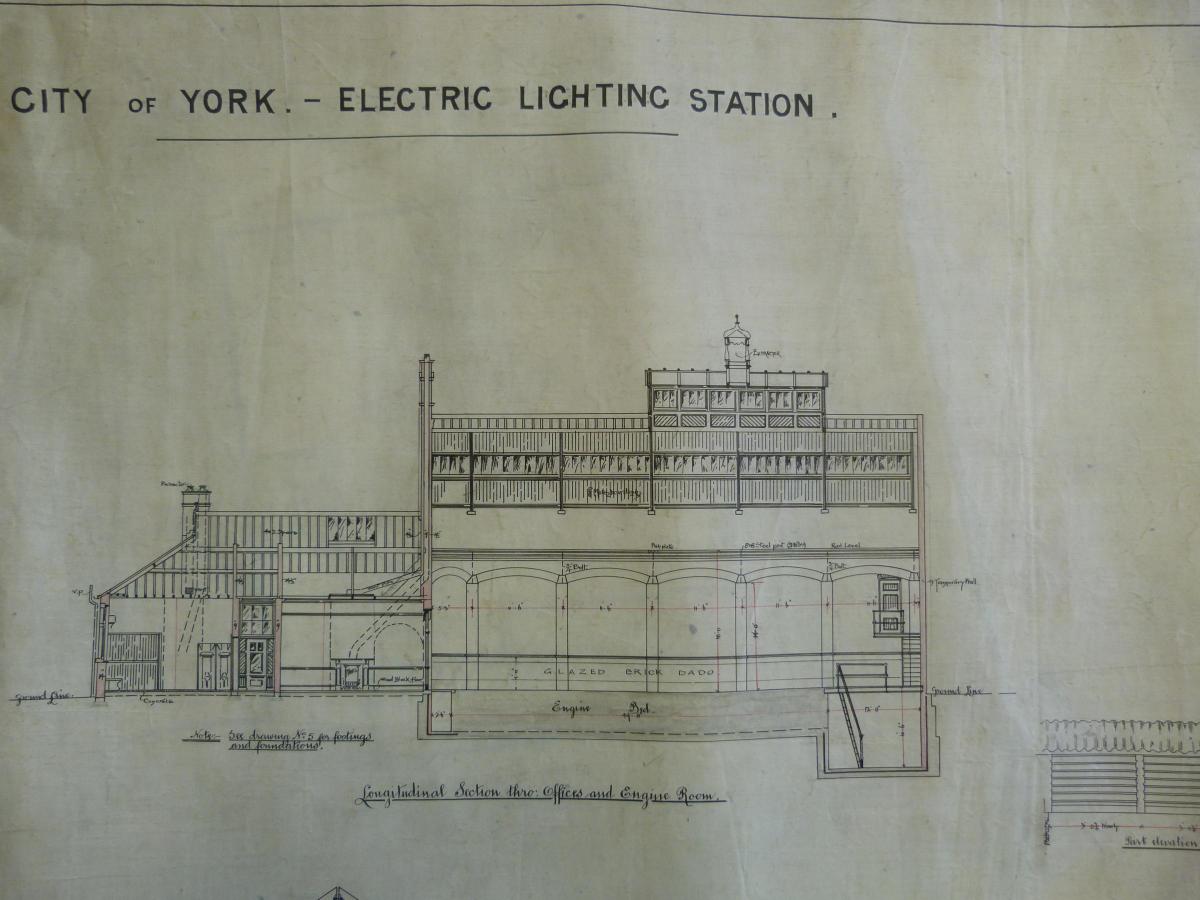

Other plans catalogued so far include a lovingly-detailed architectural drawing of the City of York Electric Lighting Station; plans from 1905 for the York City Asylum (later Naburn Hospital), which include the stipulation that storage areas for packed goods should have '1 1/2 inch White Sicilian polished marble tops'; and an 1870 plan of the old Mint Yard where the central library now is, showing stabling for travellers' horses and a row of stalls for 'gentlemen's carriages'. The street we now know as Museum Street is, confusingly, marked on the plan as Finkle Street.

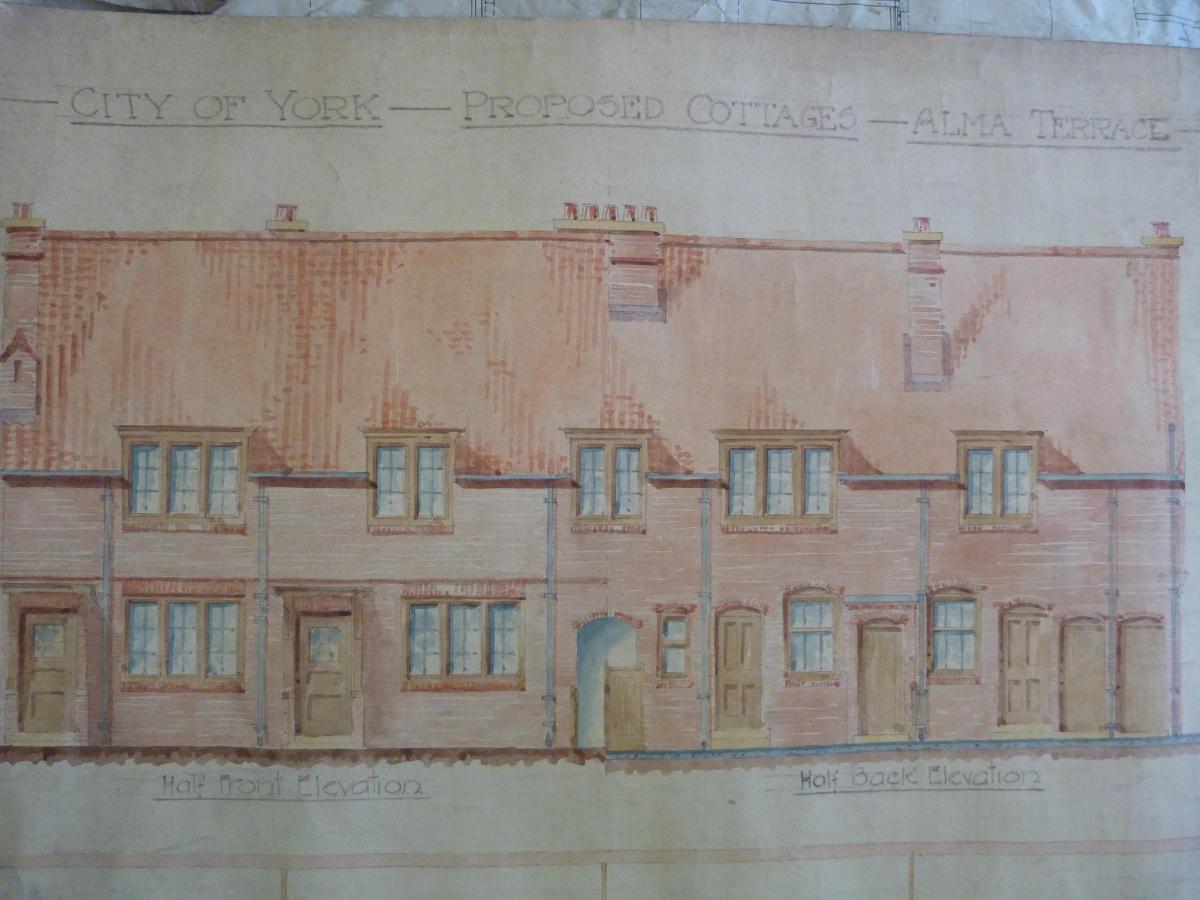

There are also architects' drawings and plans for housing schemes proposed by the council. One roll, opened just half an hour before I arrived, includes detailed drawings and plans from 1911 for a square 'proposed cottages' on Alma Terrace - a square known today as Alma Grove.

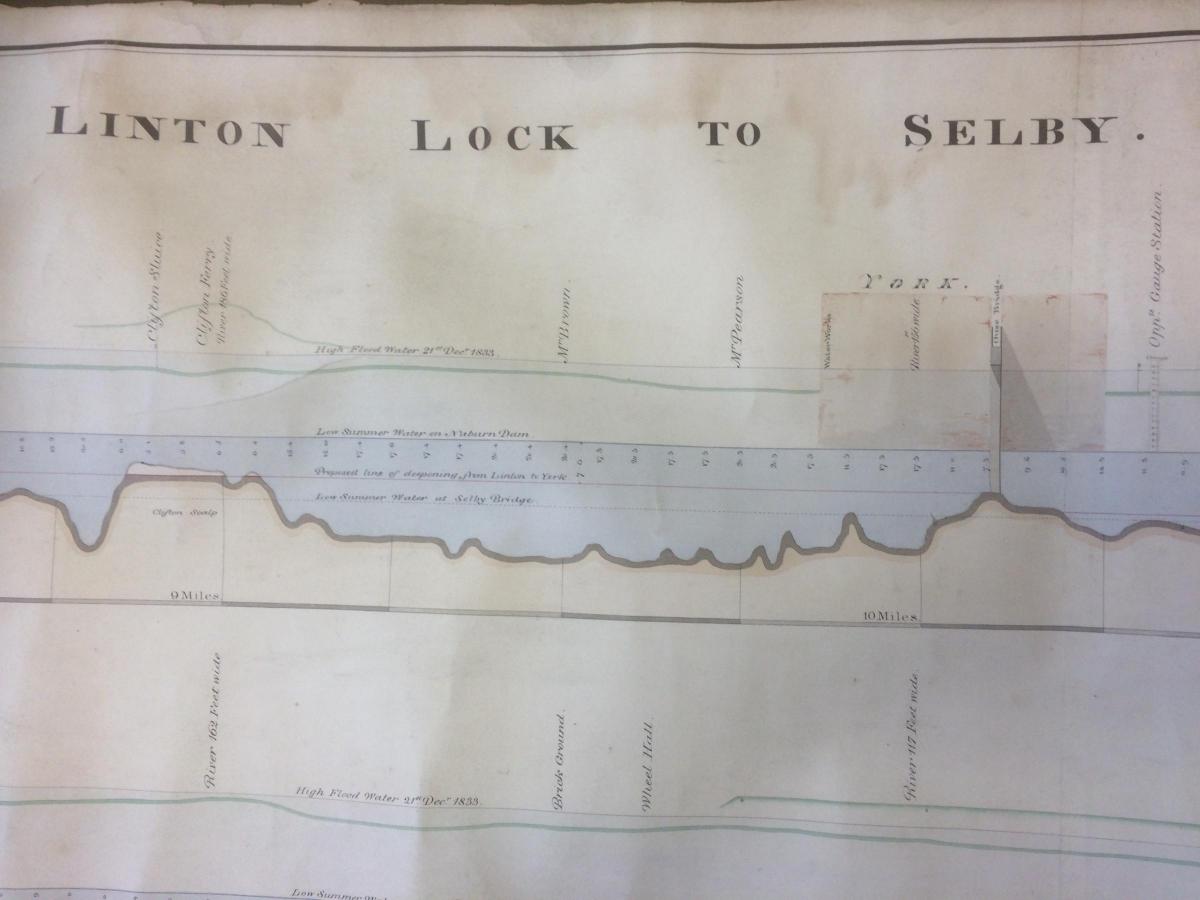

Perhaps the most striking of all the plans catalogued so far, however, is an extraordinary, six metre-long cross section showing the bed of the River Ouse for its entire length from Linton Lock to Selby.

Julie-Ann Vickers with the chart showing the bed of the River Ouse. Photo: Catriona Cannon

It was drawn in January 1834 by an engineer named Thomas Rhodes. It shows the rising and falling bed of the river - sometimes deep, sometimes shallow. Sandbanks exposed when the water levels were low are marked as 'scalps', and there's a dotted line showing the High Flood Water mark of December 1833.

There's a second, much deeper dotted line running the river's length marked simply 'proposed line of deepening from Linton to York.'

"I think they would have been thinking about trying to level out the river bed," says Julie-Ann.

Whether they ever did that or not, the result is a beautifully drawn chart that is a work of art in itself...

- You can see more images of plans and drawings catalogued by the On The Drawing Board archives team on Instagram @exploreyorkarchives

How the project is funded

The On The Drawing Board project is supported by the City of York Council and by The National Archives, The Pilgrim Trust, the Wolfson Foundation and the Foyle Foundation, for recognising the value in our project.

Explore York chief executive Fiona Williams said: "In a city that prides itself on its internationally recognisable built environment and history, these plans are of immense research and practical importance to a very wide ranging audience and will offer enormous outreach potential once catalogued. We are very excited to make this fascinating collection available to the wider public in December 2019."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here