Executions, battles, royal visits, a rampaging bear and a giant Amazonian water lily - York's Museum Gardens have had the lot. STEPHEN LEWIS dips into a fascinating new book

HEAD for the Museum Gardens on a sunny summer's afternoon (remember those?) and you can hardly move for the half-naked bodies sprawled on the grass, or the groups of picnickers spreading their blankets amid the ruins.

This lovely corner of York hasn't always been a sun-worshipper's paradise, however. At one point it may (whisper it) have been the city tip - and possibly even a place of execution.

OK, so it was a long time ago, and the evidence for it is circumstantial to say the least.

But Francis Drake (the historian, not the pirate) quotes an 'ancient manuscript' in his 1736 history of York which suggests that 'where now the Abbey of St Mary stands, was, before the conqueror's time, a place the citizens made use of to lay the sweepings of their streets and other kinds of filth in; and there their malefactors were executed'. Might be worth remembering that next time you stretch out on the grass for a snooze in the sun...

It is all very hypothetical, stresses Peter Hogarth, the co-author of 'The Most Fortunate Situation', a new history of the Museum Gardens. Drake was quoting at least third hand, and who knows what that 'ancient manuscript' he referred to was.

But it sort of makes sense. The 'conqueror', of course, was William the Conqueror. So what that manuscript is saying is that in Viking times or even earlier - possibly the days of Anglo-Saxon Eoforwic - the people of the city threw all their rubbish outside the old Roman city walls to the north of the city, and may even have brought their criminals there to be executed, too. Well, let's face it, you wouldn't want to do those things inside the city walls.

True or not, this part of York certainly has an amazing story to tell.

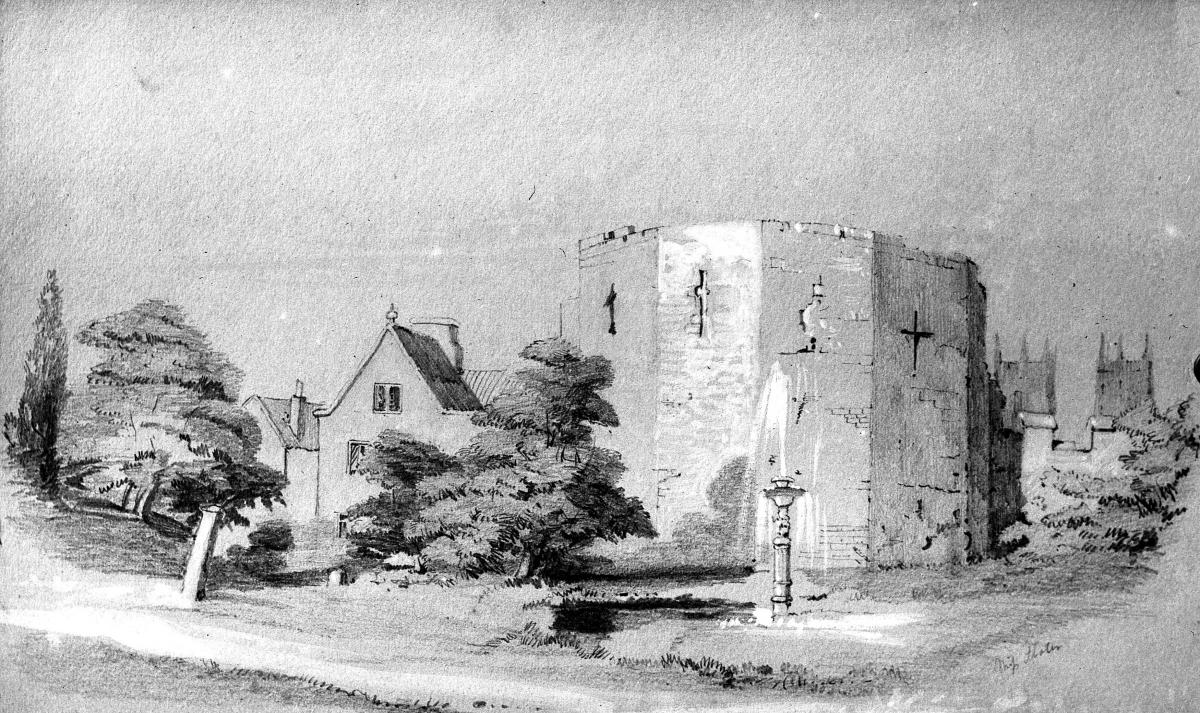

It is a story that begins with the Romans. The area that we now call the Museum Gardens lies just outside where the western walls of the Roman fortress once stood (the multangular tower is what remains of the Roman south west corner tower). There is some evidence that there was a walled enclosure of some kind, plus a street and an assortment of buildings, just outside the fortress walls.

We don't know much about what happened after the Romans left in about 410AD - that period isn't called the Dark Ages for nothing. But in his book AD 500 published a decade or so ago, historian Simon Young speculates on how, following the collapse of Roman law and order and of the civil infrastructure and supply lines needed to support a city, the Romano-British people left behind may have abandoned cities such as York, leaving them to the ghosts and shadows, and tried to scrape a living from subsistence farming.

Then the Saxons invaded, setting up first rough camps and then eventually recolonising some of the old Roman cities. Eoforwic was born. It is at about this time that, according to Francis Drake, the area outside the old Roman walls may have been used as a tip and worse.

Fast forward to the Norman conquest. In 1078 the land that is now the Museum Gardens was given to Alan the Red, the Count of Richmond. He in turn gave it to a man called Stephen, a fugitive monk who had been driven out of Whitby, so that he could found a monastery. Stephen became the first Abbot of St Mary's.

Over the next few hundred years, the Abbey of St Mary's became one of the richest and most powerful in the country. So powerful, in fact, that there were frequent disputes with the people of York - particularly over who could claim the rental revenue from Bootham. In 1262, write Peter and his co-author Ewan Anderson, quoting an ancient source, there was 'extreme violence used by the citizens of York against the abbot and Convent of St Mary in killing of their men, plundering of their goods, and burning of their houses in Bootham."

The abbot began building a defensive stone wall around the abbey precinct, partly for protection against the Scots, but also for protection against the people of York. Much of that wall still exists today.

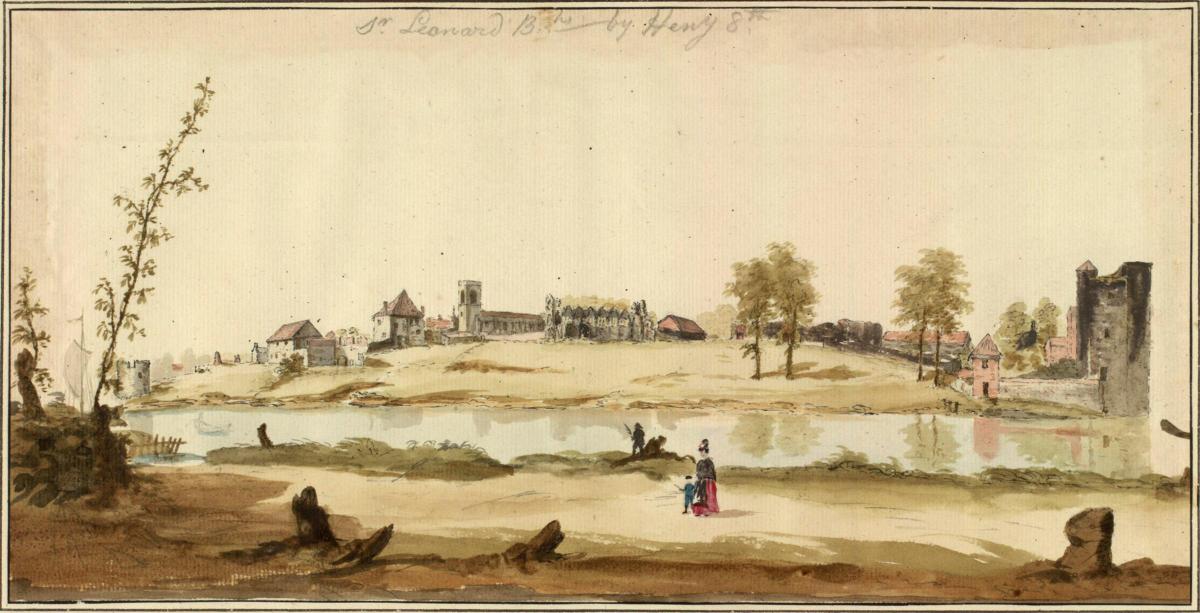

The abbey survived until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII. The Crown seized the abbey and its lands, and a 'Court of Augmentation' was charged with selling off the stone as building materials to raise money for the cash-strapped king.

Henry then realised that he needed a base for the Council of the North, which governed the unruly north of England on his behalf. More importantly, on his visit to the city in 1541, he needed a place to stay.

The city fathers got into a panic, but quickly rebuilt the half-demolished former Abbot's residence and turned it into a manor fit for a king - what is today King's Manor.

The abbey itself became a ruin, but King's Manor survived as the home of the Council of the North and the area around, used as pasture for the horses and other animals belonging to the Council, became known as the Manor Shore.

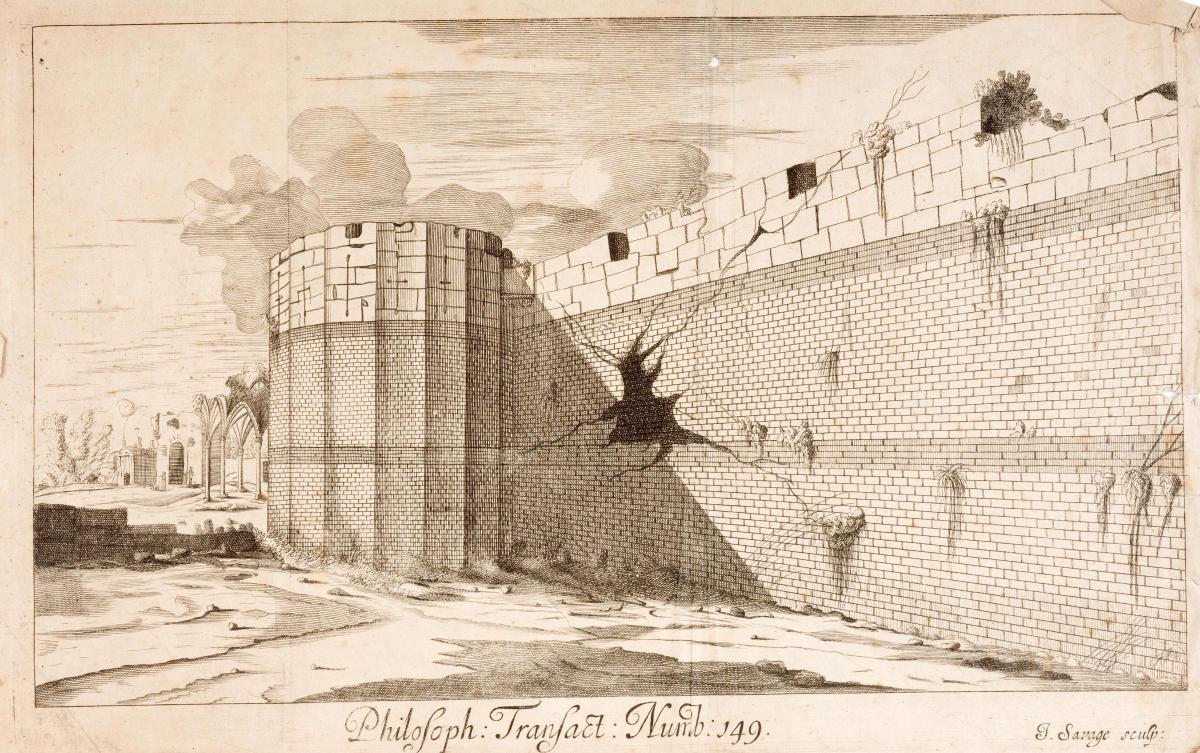

In 1644, during the Civil War, Parliamentary forces besieging York used cannon to blast a hole in the city walls. The defending Royalists were able plug the hole with earth and turf. A few hours later, the parliamentarians detonated some explosives they had planted beneath St Mary's Tower at the corner of Bootham and Marygate. Several hundred Parliamentary soldiers rushed through the breach, into an orchard and across a bowling green next to the abbey ruins, but were beaten back. The incident became known as the 'battle of the bowling green' - and if the Parliamentarians had been able to co-ordinate their attacks on the city wall and on St Mary's Tower, it might have ended differently, Peter suggests.

The 'Manor Shore' passed through various hands. In 1718, it was bought by Sir Tancred Robinson, a two-time Lord Mayor of York, who had an apartment in King's Manor and who dreamed of turning the whole area into a square of fashionable Georgian town houses, with a formal garden and a pleasure garden reaching down to the river. The plans came to nothing.

Oddly, it was a quarry on the edge of the North York Moors which was to lead to the development of the Museum Gardens we know today.

In 1821 men working in the quarry, near Kirkdale, discovered a cave containing the bones of some extraordinary animals that you wouldn't expect to find in Yorkshire - elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus and hyena among them.

The find caused a sensation in scientific circles. "It was the idea that there had once been hyenas and rhinos roaming Yorkshire," says Peter Hogarth.

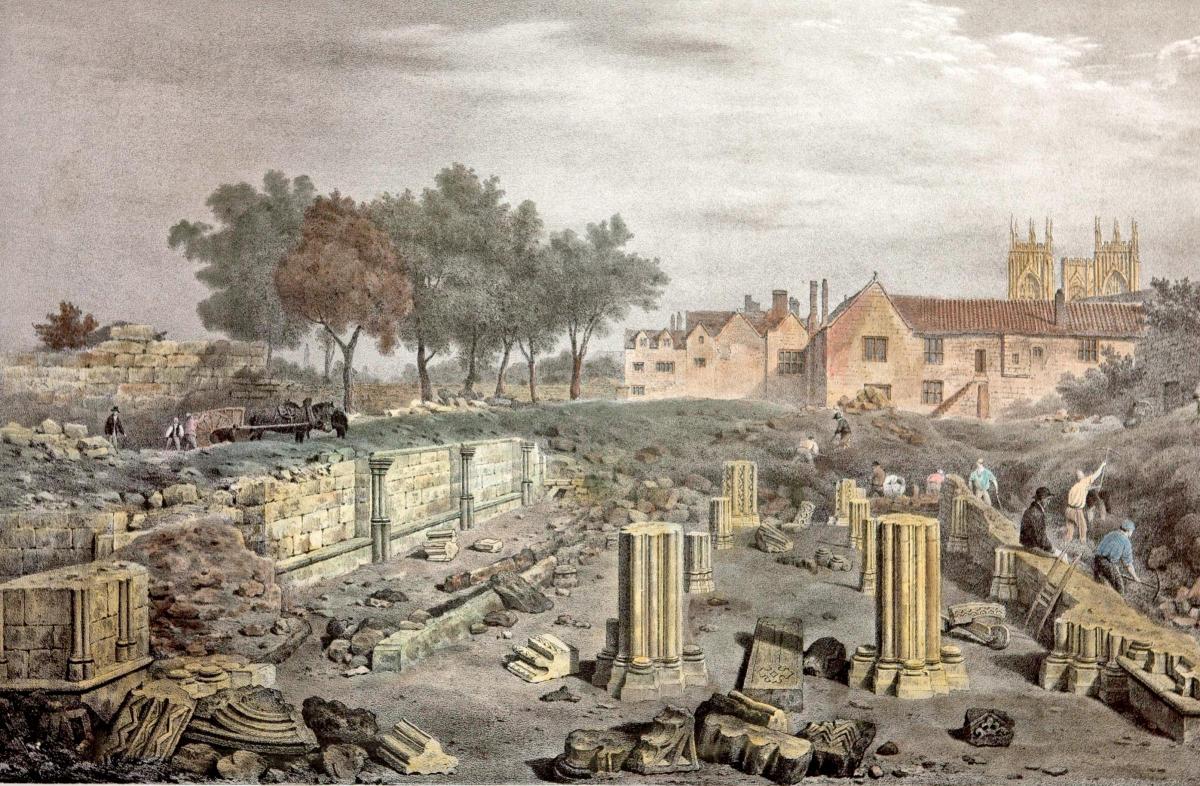

In 1822 a new organisation, the Yorkshire Philosophical Society (YPS), was formed, with the aim of setting up a museum to house the fossils, and other local objects of scientific and archaeological interest.

At first the bones and fossils were kept in a building in Low Ousegate. But in 1827 a Bill passed through Parliament allowing some of the neglected land at the Manor Shore to pass to the YPS. A new Greek revival-style museum was designed by William Wilkins, and officially opened in 1830.

A botanical garden quickly followed suit, occupying much of the area that is now the Museum Gardens. It included trees and plants from all corners of the British Empire, plus fountains, orchards, hothouses - one complete with a giant Amazonian lily with leaves so big it was said children could walk on them - and a menagerie, complete with a bear.

The menagerie may have been contained inside the multangular tower. If that is so, it proved to be inadequate. "Some time in 1831...the bear got loose and chased Professor Phillips (John Phillips, first keeper of the museum) and the Rev Vernon Harcourt into an outhouse."

The bear was subsequently sent to London Zoo, and the menagerie closed. The Amazonian lily didn't survive for long, either.

|But the Museum Gardens as we have them today owe their existence to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, and its determination to build a museum fit for the Kirkdale cave fossils...

Panel

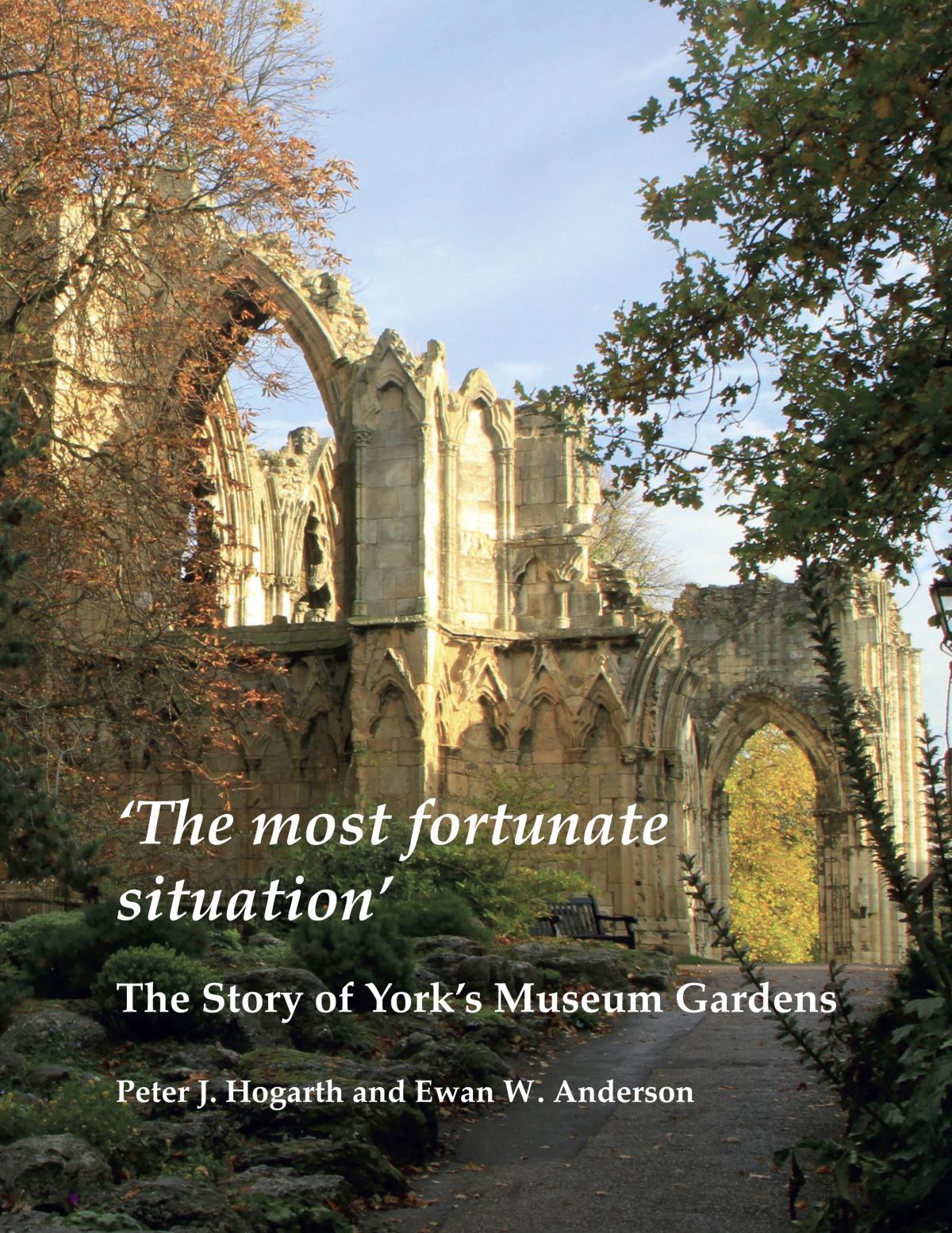

The Most Fortunate Situation: The Story of York's Museum Gardens by Peter Hogarth and Ewan Anderson is published by the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, priced £25.

It will be launched on Tuesday (November 6) at the Yorkshire Museum, and will be available from the museum shop or from the YPS lodge in Museum Street.

The book was written as part of the preparations for the YPS's 200th birthday in 2022.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel