What class are you? Do you even know any more?

It’s not so easy to tell these days. A generation or two ago, if you worked on the factory floor at Rowntrees or made your living building railway coaches at York Carriageworks chances are you’d have thought of yourself - and your family and friends - as working class. Hold down a white-collar job at the local bank, meanwhile, and you'd have felt solidly middle class.

Things are much more complicated today. Many of our traditional working class jobs - industry, manufacturing, mining - have gone, as we moved towards a service economy. Today, many of those who would once have thought of themselves as working class are doing a completely different kind of job, working in bars, restaurants or call centres.

Others - agency workers, self-employed technicians or support staff - are officially classed as self-employed, and therefore have few employment rights. And many are stuck on or only slightly above the minimum wage, with few prospects of ever really earning decent money.

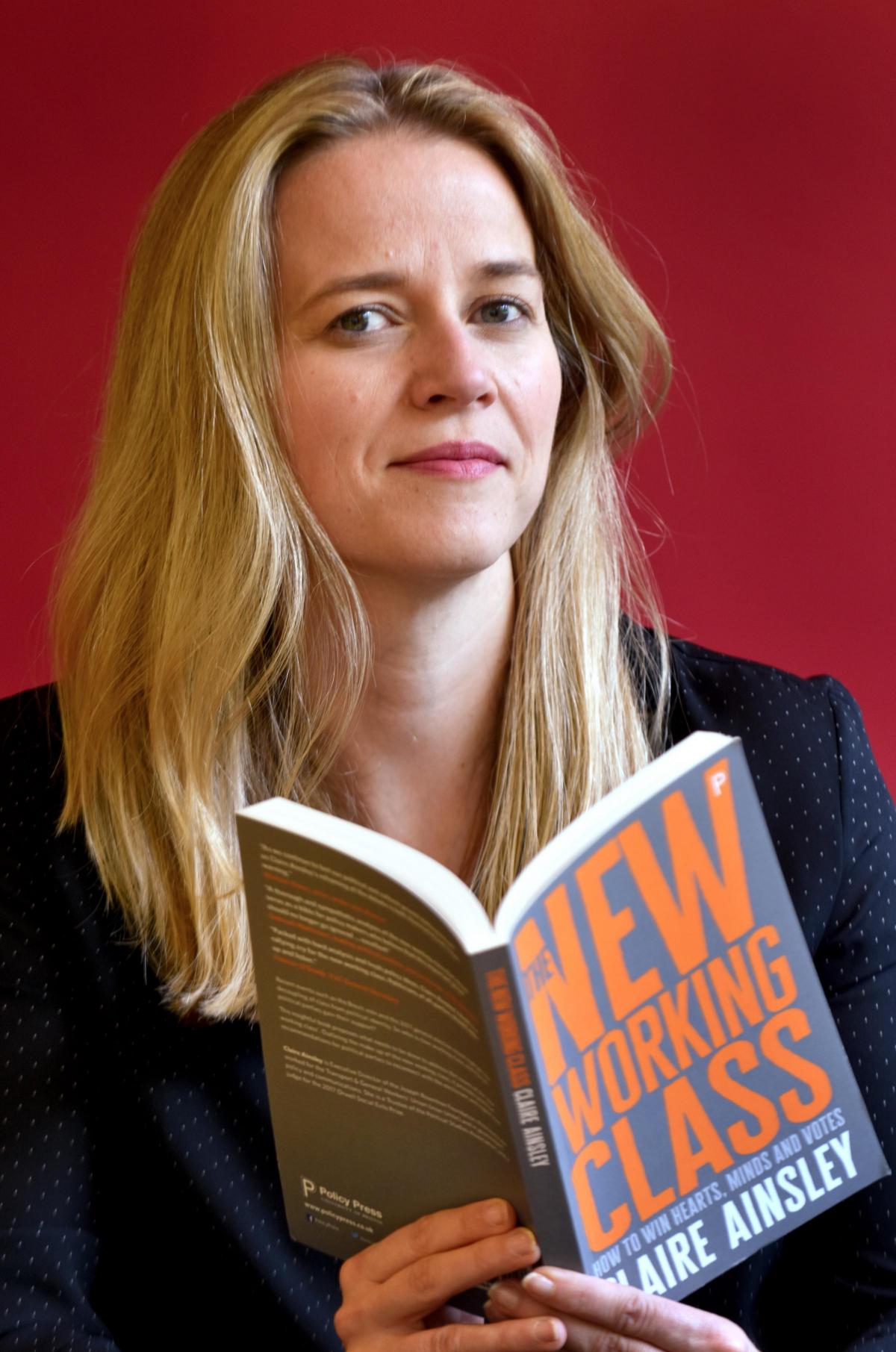

These are the people that Claire Ainsley writes about in her new book The New Working Class: How to Win Hearts, Minds and Votes. And they are people who are, by and large, overlooked and unregarded by politicians (including Labour ones, Claire says) and so are largely missing out on the opportunities others take for granted.

The new working class is very different from the traditional working class of our fathers and grandfathers, says Claire, the executive director of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Where members of the 'traditional' working class were often united by shared values, interests and communities, the new working class is much more diverse, she says.

Traditional working class: workers on an early production line at York Carriageworks

She has based her definition of this 'new' working class on the Great British Class Survey of 2013. It includes three distinct groups of people:

- the 'traditional' working class: older people (average age 66) with low incomes and little in the way of savings, but quite likely to own their own home

- emergent service workers: younger city people with not much money and poorly paid, insecure jobs who nevertheless have lots of friends and active social lives

- the 'precariat': the poorest, most deprived group, unemployed or trapped in low-paying work because their education didn't equip them to improve their lives

It is actually even more complicated than that, Claire says - because the members of these three groups increasingly include people of different ages and of different ethnic backgrounds and cultures. And where in the past the working class breadwinner would usually have been the man of the house, today it is just as likely to be the woman - often holding down more than one part-time job to try to make ends meet.

The modern idea of class is all much more shifting and chaotic than it used to be - so it can be harder for us to identify with one class or another.

Claire herself admits she finds it difficult. Her grandfather was a Durham miner who left the pits to become a policeman in London. He was clearly working class.

Her father was a telephone engineer, her mother a secretary. But she herself came to the University of York to study politics, before making a career in communications and PR with trades unions an a Government agency.

The mum of two now holds down a good job in York. So is she middle class? Class is partly in the mind, she says, implying she's reluctant to give up her working class roots. "But I'm doing quite a middle class job."

New working class? Staff in a call centre

The point is that when it comes to members of the new working class, there is very little that they all share in common, she says. There are really just two things. They're all struggling, on low to middle incomes with probably not much job security. "And they have much less attention paid to them by national political parties than people of other classes. None of the political parties have really grasped who they are, what they think, or what they need."

That may explain why so many working class people are turned off by politics these days. They just don't feel politicians speak for them any more, she says.

Politicians have tried to show they understand, with their talk about 'hard working families' and the 'just about managing', she says. But actually they just don't get how difficult and insecure many people's lives are. "People in power are insulated," she says.

The reality today, she says, is that we live in a low-wage, de-regulated, de-unionised society in which 'millions of people don't have the type of security that their parents enjoyed during the post-war era.'

So how did we get here? Why is modern Britain so divided, with so many people struggling to get by with none of the security that their parents took for granted?

It is partly the effect of Britain's post-war decline, she accepts. And it is partly the result of a changing economy - the shift from industrialisation to a service economy.

But it was partly deliberate policy, too. The governments of the 80s and 90s (she declines to use the Thatcher word, but it's hovering there in the background) made a deliberate, ideological choice to pursue a laissez-faire, low-wage, deregulated economy in which the power of the unions was broken, she says.

Other European countries - Germany, for example - managed the shift to a consumer economy in a way that enabled the least well off to do better. Britain chose not to. It is as if we forgot that the economy should be there to serve the interests of people and families and communities, she says.

So what can we do to make Britain work better today for the least well off?

Her book is a deliberate attempt to kick-start a conversation about exactly that, she says. It includes some concrete suggestions - such as a dedicated tax for health care, and an employment rights charter (see panel).

But first, politicians have to learn to listen and to try to understand the real difficulties many people today are faced with. It is in their own interests to do so if they want to win votes, she says.

"They need to understand this much newer, more diverse working class," she says. "They cannot just try to divide and rule."

- The New Working Class: How to Win Hearts, Minds and Votes by Claire Ainsley is published by Policy Press priced £12.99

Claire Ainsley's prescription for a better, fairer Britain

National

- a dedicated health and social care tax to ensure the NHS and or social care system can continue to provide for all into old age

- an employment rights charter to guarantee workers' rights such as sick pay for all

- businesses should be incentivised to provide education and training

- -greater devolvement of wealth away from London to the regions, though transfer of state activities but also incentivisation of businesses to invest in the regions

- a points-based system for migration

- family incomes should be safeguarded

- new state-backed guarantees on health and pre-school education

- a new focus on adult learning, to enable people to retrain later in life so as to escape the poverty trap

- UK businesses to be selected for state contracts if they contribute to local communities

Local

Local politicians - in York and beyond - have a great opportunity to rethink how citizens can become involved in shaping their city and community, says Claire Ainsley. The My York Central community group, which led the recent consultation over the future of the huge York Central site behind the railway station, was a good example of how that can work.

There are often barriers which stop people being able to have their say, she says - but making sure that a range of voices are heard is vitally important.

"Planning ahead so that the opportunities for investment and progress are channelled into benefits for York's citizens and making sure businesses are part of contributing to a strong community is vital," she says. "Decent wages, affordable housing, and training opportunities should be at the heart of any development."

Case Studies

Kelly-Marie Ainsley (no relation of Claire Ainsley)

Kelly-Marie, 34, a mother of four from The Groves, has been unemployed for four years because of illness. "It is hard for me even to get up and get out of the house," she says. Even when she could work, it was in bar jobs or as a waitress: jobs which just about kept a roof over her head. "There was no money left for luxuries." She sees no prospect of ever owning her own house.

Kelly-Marie Ainsley

Kelly-Marie doesn't like talk of class. "We shouldn't be putting people into classes. We are all the same," she says.

But she doesn't think politicians have any idea what life is like for people like her. Because they're wealthy, they don't think there's anything wrong, she says. "They don't understand the people who are poorly, or who are struggling day in, day out." If they did, how could they have let the NHS get into the state it is in, she says? "It has really deteriorated over the last ten years. It is horrible what has happened."

John, 53, self-employed computer repair technician

Classing him as self-employed is a bit of a cheat, says John (not his real name). It is a way of massaging the unemployment figures: he should really be described as 'under-employed'.

He makes a regular 'top-up' benefit claim, which kicks in when his net income from doing freelance computer repair and maintenance work falls below £270 a month - as it does sometimes. Last month, he says, he turned over £500, but the £100 top-up kicked in because after he had paid his travel expenses and other business costs, his net income from work fell below £270.

He's just barely managing to get by, in other words, and often reliant on benefits. But because of the top-up benefit he claims, he's not officially classed as unemployed.

Until recently, he slept at a friend's house because he had nowhere of his own. Now, he pays £100 a week for 'a scabby room in Tang Hall'.

John describes himself as a member of the 'precariat', the most deprived sector of the new working class. He's a single white man, which he feels puts him at a disadvantage. And he's angry with politicians - the Conservatives in particular. They understand perfectly well what life is like for people like him, he says. "They just don't care."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel