Archivist Julie-Anne Vickers is cataloguing the very unsanitary history of York, as captured in its health records. STEPHEN LEWIS reports

IN 1873, York appointed its first Medical Officer of Health. Dr Samuel North's job was to improve the overall health and hygiene of the city and its inhabitants. It was to be a tough challenge.

York in the 1870s wasn't the (mostly) clean and pleasant city it is today. It was, not to put too fine a point on it, a midden.

Sewage arrangements were inadequate, with many houses not connected to drains. Outdoor open privies, many of them rarely emptied, stank. Scavengers - the men employed by the city corporation to clean out privies and sewers - often left a trail of filth in the street behind them when they did so.

There was far too much unsanitary, overcrowded housing, particularly in Walmgate, Hungate and the Groves; piggeries and slaughterhouses operated from within the city walls; and unpasteurised milk produced in family dairies and improperly stored was widely sold, spreading diseases such as typhoid. Outside the city walls there were mountains of stinking dung, and pools of stagnant, filthy water.

Little wonder that the average life expectancy of people living in York was just 36. The reason for that distressingly-short expected life span was the high rate of infant mortality - children who died in childbirth, soon after they were born or while they were still young. Childhood was a dangerous time, says Julie-Anne Vickers, the archivist at Explore York who has been tasked with cataloguing the city's extensive medical and public health records. "If you made it to your 20s, you could expect to have a reasonable lifespan into your 50s."

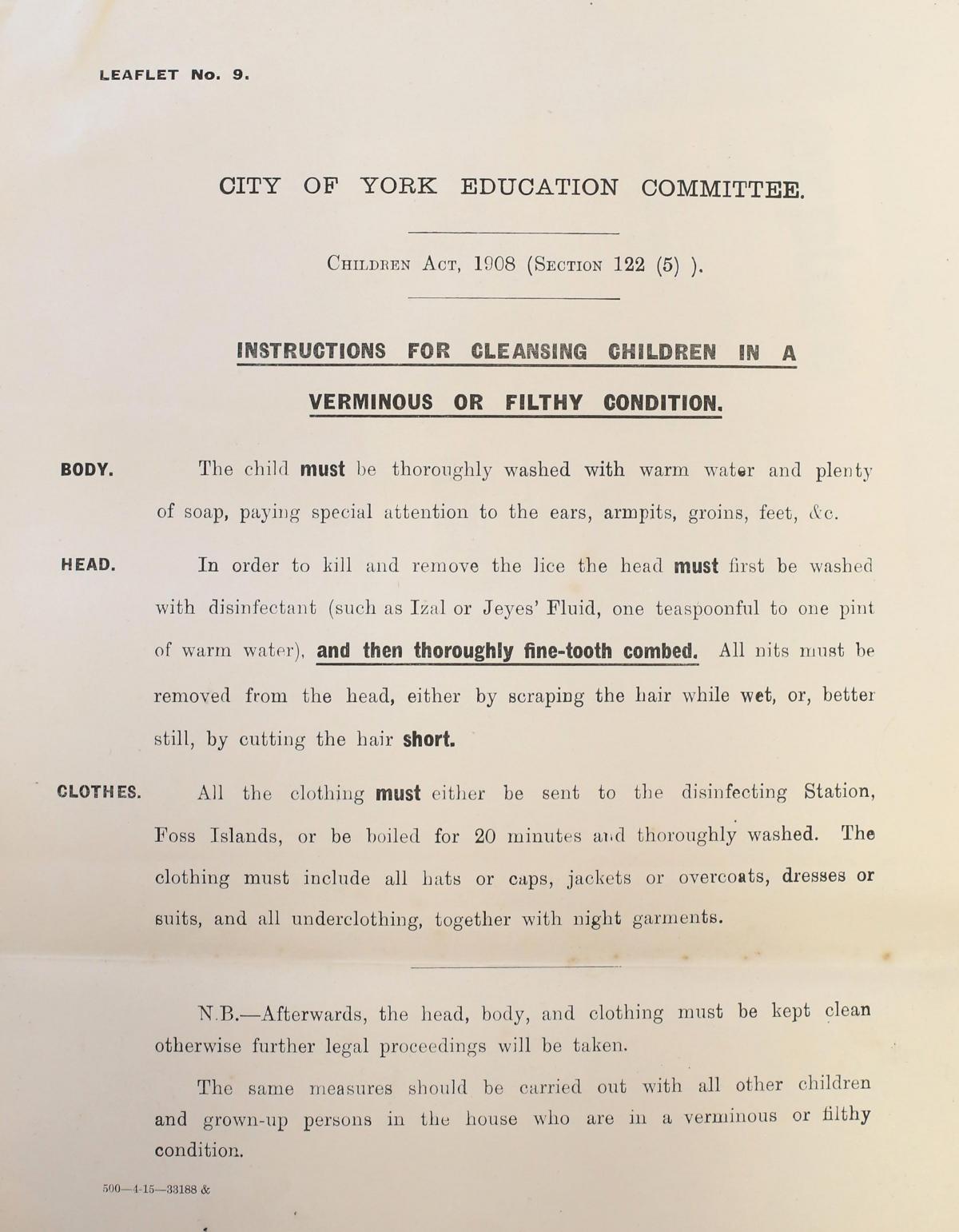

A leaflet giving instructions for the cleansing of verminous children. From the records of York's Medical Officer for health

Not every street in York was filthy, Julie-Anne concedes. The main thoroughfares, lined with grand Georgian buildings, looked quite presentable. "But as soon as you got off them..."

York's problem in Victorian times wasn't that it had undergone a massive population explosion in the way that cities like Manchester and Liverpool had. It was more to do with the fact that York was a city hemmed in within its ancient city walls. All human life and activity was there, squeezed into a narrow space that couldn't really expand. Immigration, much of it from Ireland, had led to massive overcrowding in slum quarters such as Walmgate in particular.

Diseases such as typhoid, typhus, cholera, scarlet fever, smallpox, diptheria and TB were rife. There were, of course, no antibiotics. And even diarrhoea was a killer. As late as September 1900, the health office in York reported that deaths from diarrhoea had occurred in no fewer than 55 streets across the city.

In 1873, both Dr North, the city's new Medical Officer of Health, and a new 'chief sanitary inspector' were brought in to try to do something about the appalling squalor and the disease it engendered.

They were given a range of responsibilities and associated powers, which included:

- prevention of infectious diseases

- disinfection (of buildings and people)

- housing inspection and slum clearances

- street cleaning and improvements

- abatement of public nuisances

- improvement of sewerage and drainage

- regulation of midwives and maternity services

- control of livestock and trade

The work of Dr North and his successors was overseen first by York's Urban Sanitary Authority and then, from 1900, the York Health Committee. Being public bodies, they kept meticulous written records: records that open a fascinating window on what York was like in the past.

Julie-Anne Vickers looking through the records of York's Medical Officer for Health

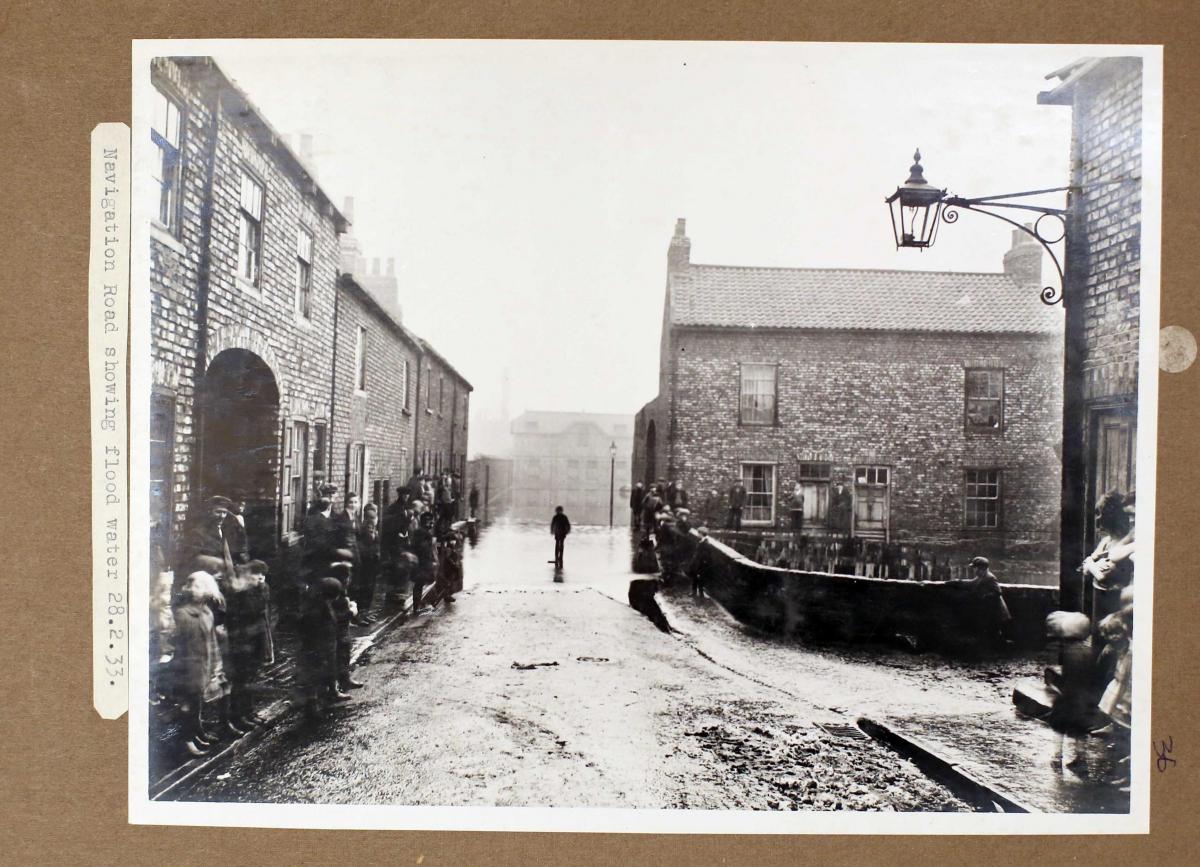

Julie-Anne is now in the process cataloguing those records, along with earlier city health records and later photographs taken when planning slum clearances, as part of Explore York's ongoing Past Caring project, which aims to make the city's workhouse, poor law and health records more publicly accessible.

On these pages we include a few examples from the health records. We recommend that you hold your nose while reading...

- To find out more about the Past Caring project, visit: https://citymakinghistory.wordpress.com/past-caring-project/

Twitter updates from @pastcaringyork

FROM THE YORK HEALTH RECORDS

OVERCROWDING

15 Jackson Street, occupier James Lynch, owner Mr R Robinson of Lowther Street

Report of the chief sanitary inspector, date unclear but early 1900s:

"I beg to report that I have inspected the above-named premises re overcrowding. The house consists of kitchen on the ground floor and two bedrooms.

"The bedroom with fireplace... is occupied for sleeping purposes by Mrs and Mrs Lynch, James, 3, and Harry, 1 year 9 months.

"The bedroom which has no fireplace is occupied for sleeping purposes by John 15, Harold, 11, Tom, 9, Louisa, 14, Doris, 7.

"John, 18 years, sleeps on the sofa in the kitchen. The kitchen wallpaper is very dirty. The floor of the kitchen is paved with flooring stocks and is in a very defective condition, the bricks being broken and sunken."

SQUALOR

From the report of the 'assistant inspector of nuisances', October 13, 1905

17-19 Smales Street. "I beg to report I have inspected the back road at the rear of the above houses re corporation scavengers leaving back road in a filthy state after cleansing out the privies. At the time of inspection the back road was clean, but the occupiers of the above houses complain that they have to cleanse the road after the privies have been cleansed out. Liquid leaks from the carts and remains on the road."

From the report of the assistant inspector of nuisances, April 8, 1905

Malt Shovel Inn Yard, Walmgate. Owners, Palliser brothers, grocers.

"I beg to report I have again inspected the piggeries at the above premises. They were in a filthy condition... not very offensive, but would become so at the time of cleansing."

DISEASE

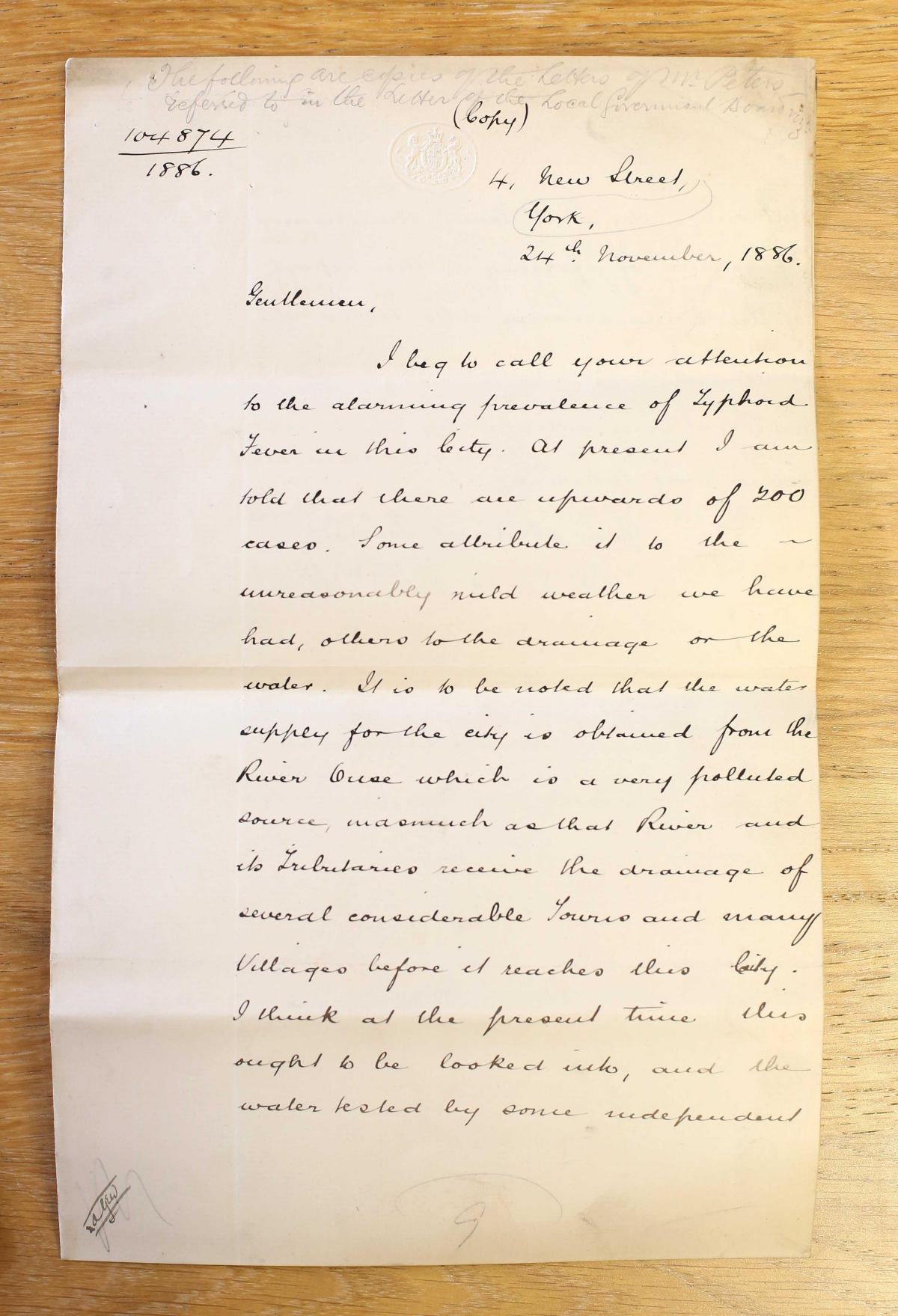

Letter from the Medical Officer of Health, November 24, 1886

"Gentlemen, I beg to call your attention to the alarming prevalence of typhoid fever in this city. At present I am told that there are upwards of 200 cases. Some attribute it to the unseasonably mild weather we have had, others to the drainage or the water. It is to be noted that the water supply for the city is obtained from the River Ouse which is a very polluted source, inasmuch as that river and its tributaries receive the drainage of several considerable towns and many villages before it reaches this city. I think at the present time this ought to be looked into."

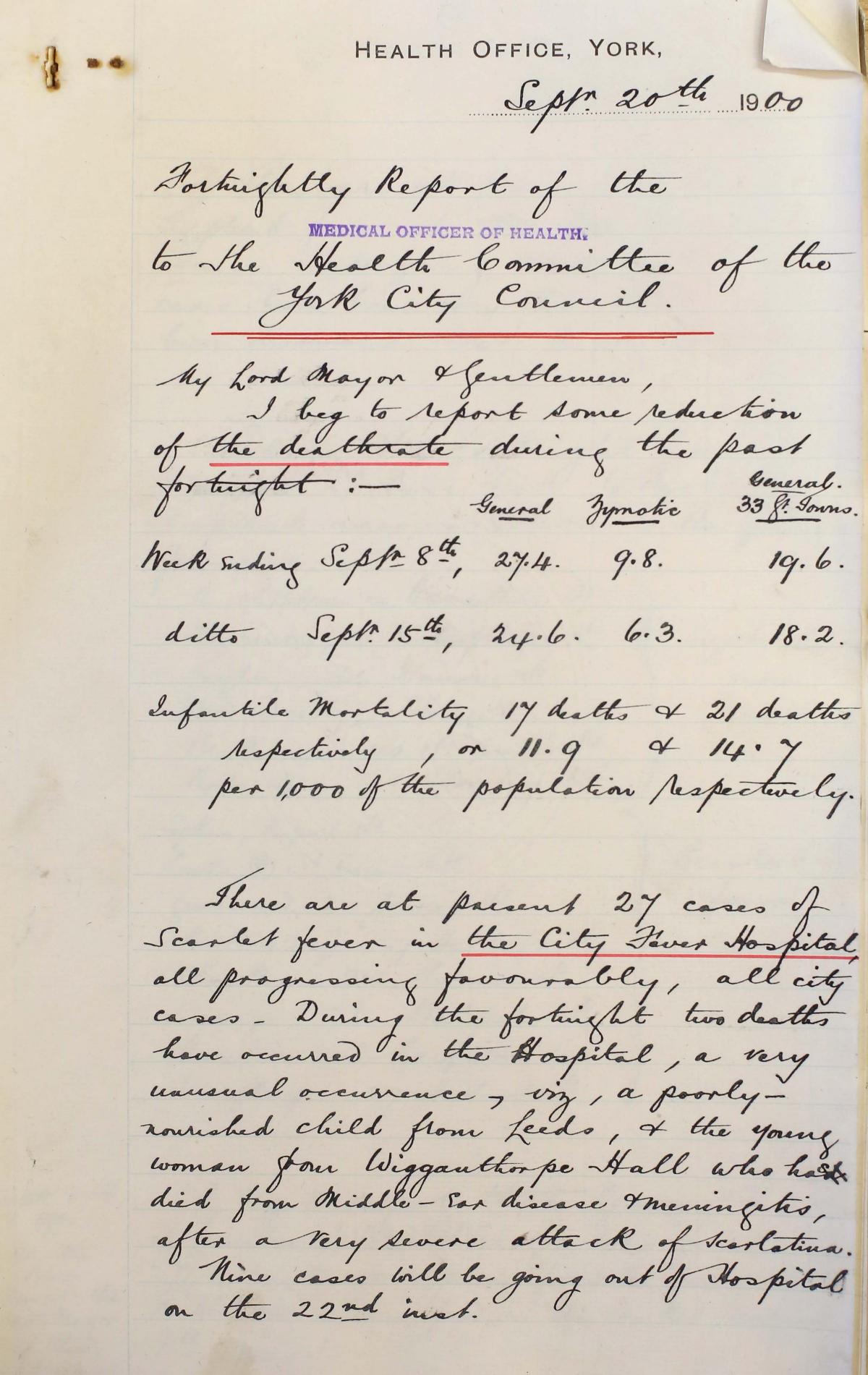

Medical officer of Health, fortnightly report to the health committee of York City Council, September 20, 1900

"My Lord mayor and gentlemen,

"There are at present 27 cases of scarlet fever in the city fever hospital, all progressing favourably, all city cases. During the fortnight, two deaths have occurred in the hospital.... viz, a poorly nourished child from Leeds and the young woman from Wigganthorpe Hall who has died from middle-ear disease and meningitis."

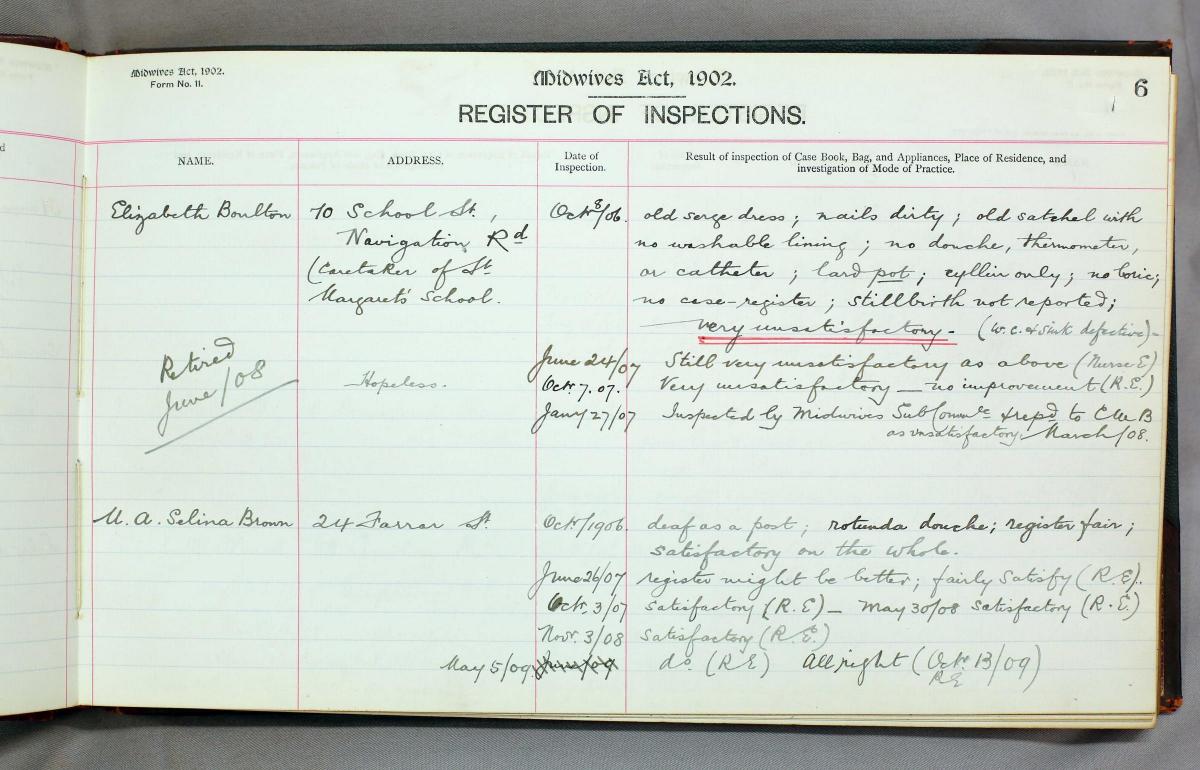

REGULATION OF MIDWIVES

The Midwives Act, 1902 was introduced in an attempt to reduce maternity and infant mortality deaths by improving the standard of midwives who had previously been unregulated. Regular inspections of midwives were carried out in accordance with the Act, and recorded in a register.

From the Register of Inspections, October 8, 1906, entry for midwife Elizabeth Boulton, of School Street, Navigation Road:

"Old serge dress; nails dirty; old satchel with no washable lining; no douche, thermometer or catheter... no case register; stillbirth not reported. Very unsatisfactory."

After three more unsatisfactory inspections, midwife Boulton retired in June 1908.

VERMIN

City of York Education Committee, leaflet No 9 in respect to the Children's Act, 1908.

"Instructions for cleansing children in a verminous condition.

"Body. The child must be thoroughly washed with warm water and plenty of soap, paying special attention to the ears, armpits, groins, feet etc.

"Head. In order to kill and remove the lice the head must first be washed with disinfectant (such as Izal or Jeyes' Fluid...) and then thoroughly fine-tooth combed. All nits must be removed from the head, either by scraping the hair while wet, or, better still, by cutting the hair short."

"Clothes. All the clothing must either be sent to the Disinfecting Station, Foss Islands, or be boiled for 20 minutes and thoroughly washed."

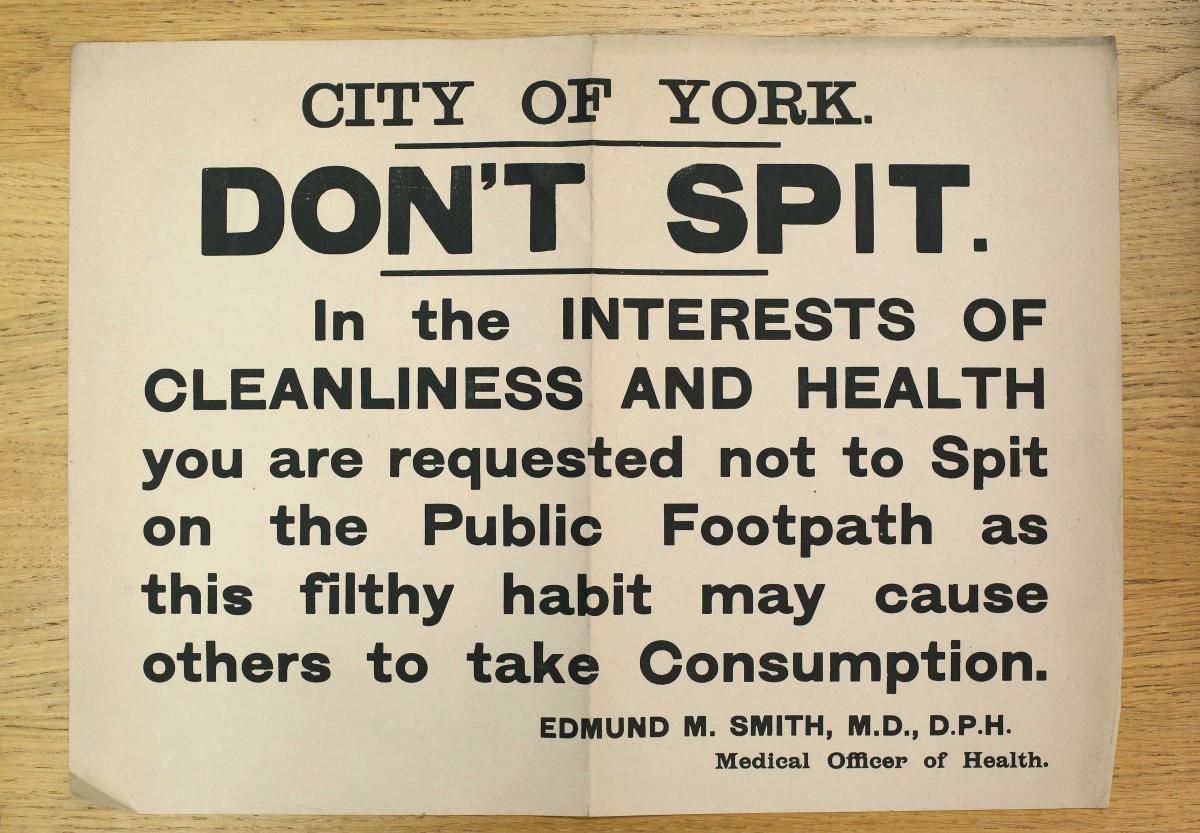

HYGIENE

Public notice posted by Dr Edmund M Smith, who became Medical Officer of Health for York in 1900:

"DON'T SPIT. In the INTERESTS OF CLEANLINESS AND HEALTH you are requested not to Spit on the Public Footpath as this filthy habit may cause others to take Consumption (ie catch TB)."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel