A chance encounter with war correspondent John Pilger inspired a North Yorkshire gap-year student to take up documentary photography, says RUTH CAMPBELL. Now Mark Read travels the world capturing incredible images for publications such as National Geographic and Time magazine.

FROM remote Siberian tribes living in one of the coldest inhabited places on Earth to Colombian cocaine farmers in the heat of the Amazon jungle, photographer Mark Read has captured a stunning array of images through his camera lens in the past 20 years.

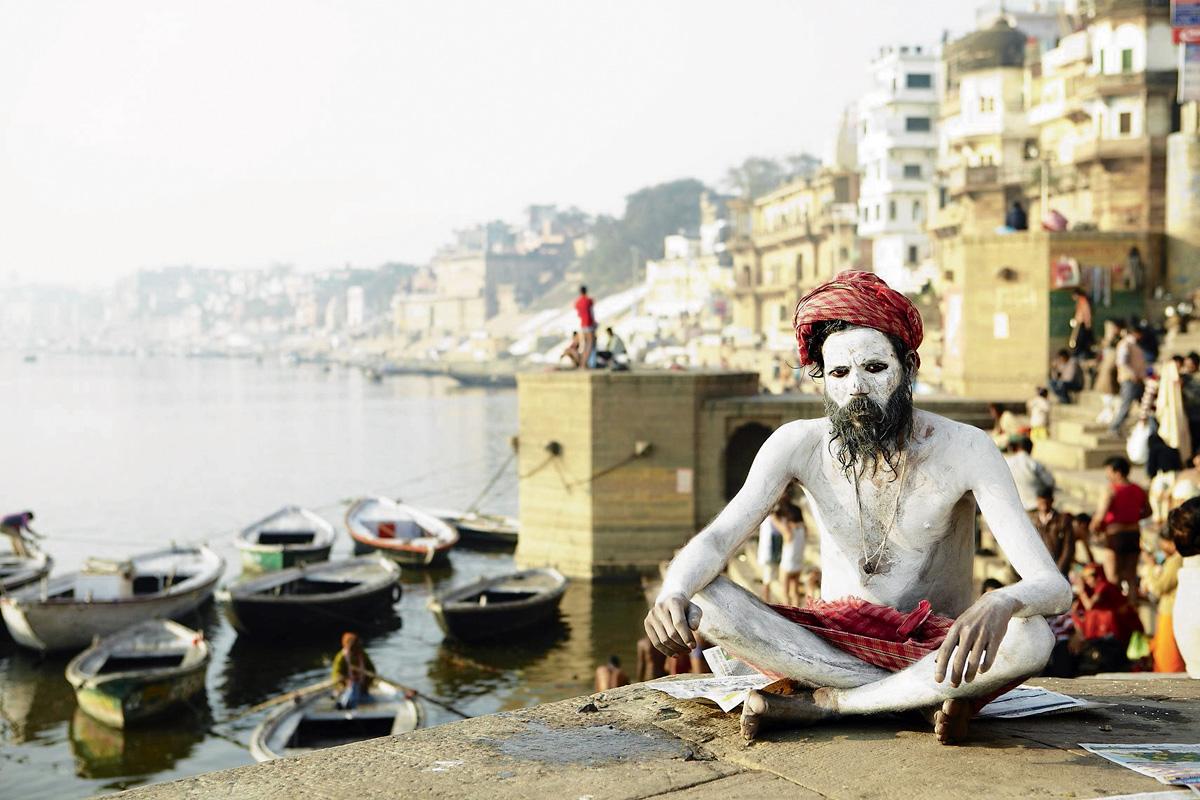

His work for publications such as National Geographic and Time magazine has taken him to every corner of the planet, from documenting the lives of child soldiers living in the wake of civil war in Sierra Leone to picturing reggae musicians in Jamaica, firewalkers in Mauritius, Hindu pilgrims in the ancient Indian city of Varanasi and former child slaves in Togo.

The father of two, who grew up in North Yorkshire, has spent six months of every year working abroad since he first came to prominence when, fresh out of photography college, he joined genetic anthropologist Dr Spencer Wells, travelling across the newly independent central Asian states of the Soviet Union to help chart the migration patterns of mankind. This led to the National Geographic Genographic Project.

As he takes time out from his busy schedule to talk about his work – having just returned from Cambodia and about to set off for Cuba – he reflects on the landscape he thinks of as home. Ironically, one of the few parts of the world he hasn’t photographed is the countryside of North Yorkshire.

Born in Harrogate and educated in Ripon, it is the Moors and Dales he yearns to capture now. When one of the magazines he works for, the BBC’s Lonely Planet Traveller, recently ran an article featuring pictures of the area, he felt a pang of regret. “There were photographs of Brimham Rocks, beautiful villages and wild moorland. I would have loved to have done that,” he says.

The son of an RAF group captain, Read, 46 and based in London, boarded at Ripon Grammar School, where he felt a sense of rootlessness. “It’s a common thing with Forces children. I feel jealous of ‘proper’ Yorkshire people, with the strong accent and real affinity with the place,” he says.

But it also instilled in him a spirit of adventure. “Growing up in an Airforce family meant that every three years we moved to a new home. Although this might seem disruptive, it instilled in me an adventurous streak and I’ve been restless ever since.”

After A-levels, Read spent two years travelling in Australia and South-East Asia while deciding what to do with his life. “I was trying to find myself, I suppose,” he says.

It was an incredible chance encounter with war correspondent John Pilger which first captured Read’s imagination and encouraged his enthusiasm for documentary photography. He stumbled across the legendary journalist at a party in Australia attended by a number of journalists who had reported on the Vietnam War.

“John Pilger said something I will always remember: ‘Journalism is the privilege of witnessing history’. It was an epiphany. I was seduced by it all and I thought: ‘This is what I want to do’.”

As a teenager, he first started taking pictures with a small plastic camera during a road trip through the southern states of America.

“I wasn’t academically minded. My first big outlet creatively came during my gap years after leaving school. I took quite a few pictures and fell in love with the idea of travelling and stories and people,” he says.

Being diagnosed with dyslexia in his 20s was revealing, he says. “It probably affected the way in which I learnt things. A lot of photographers and film makers have dyslexia. A lot of it is to do with the way the brain processes things.”

His talent became obvious when he began studying photography at the London College of Printing in his early 20s. One of five students to win a coveted place working for Insight travel guides while still studying for his degree, he was soon combining his love of travel with his passion, sent on all-expenses-paid trips to photograph people and places all over the world.

While the others squabbled over getting to cover cities like Paris, Milan and Rome, Read gravitated towards more unusual locations. “It was 1992. I went to Prague and Budapest, where not many people were going. The Berlin Wall had come down two years earlier, Prague was exploding, coming out of a dark period. Every city has its moment, I was lucky enough to be there.”

He continued working for Insight after he graduated, while searching out projects that inspired him. He travelled to Colombia with the Catholic aid charity Cafod, where he lived with cocaine farmers in an area protected by far left-wing guerrillas.

“I had been looking for a project in Latin America and before I knew it, I was paddling a canoe in the middle of the rainforest. I was given a horse and travelled for two weeks with a Jesuit priest, who visited these communities once a year to marry couples and bless the dead. I photographed one family with £100,000 of cocaine being balanced on scales on their kitchen table in front of me.”

His first big break came when, through a friend, he met Dr Spencer Wells, who was carrying out research into our human genetic roots. Wells was about to set off on an expedition to complete the maps charting the migration routes our ancestors took 60,000 years ago, when humans first ventured out of Africa and Read offered to join him as photographer.

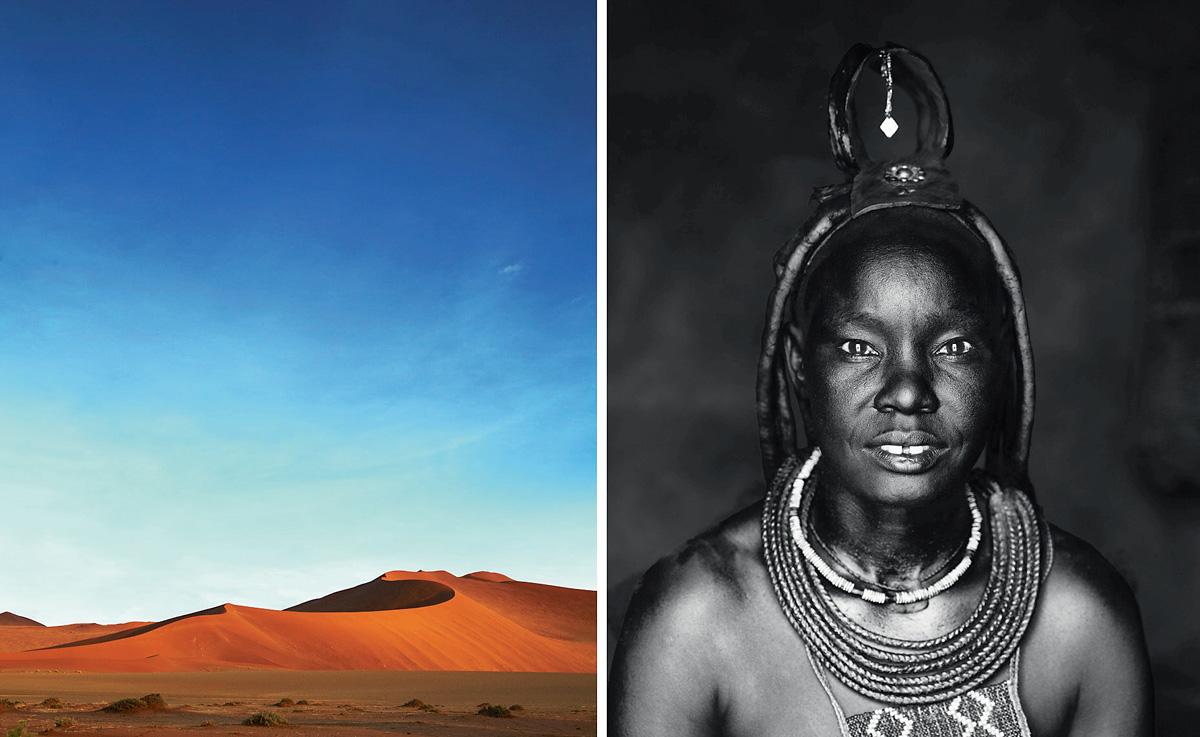

The pair drove for six months from London to Siberia, through the Caucasus, Iran and most of the “stans” of central Asia. During the trip they collected blood samples and Read shot portraits of the most isolated, remote peoples on the planet. The data they collected from these indigenous communities was invaluable in helping to answer fundamental questions about where humans originated and how we came to populate the Earth.

As a result, Read’s first major photographic project after leaving college ended up in what he describes as the “Holy Grail of photography”, National Geographic magazine, and was also made into a book. “I was lucky. I had struck gold,” he says.

He went on to work for a range of publications, including the Sunday Times, Sunday Telegraph and The Guardian, as well as for TV companies such as the BBC and Channel 4 and publishing companies such as Random House and HarperCollins. His photography illustrates bestselling books such as Gordon Ramsay’s Kitchen Heaven and magazines such as Jamie Oliver’s Jamie. But it is his work on projects for charities in the developing world that he finds most rewarding.

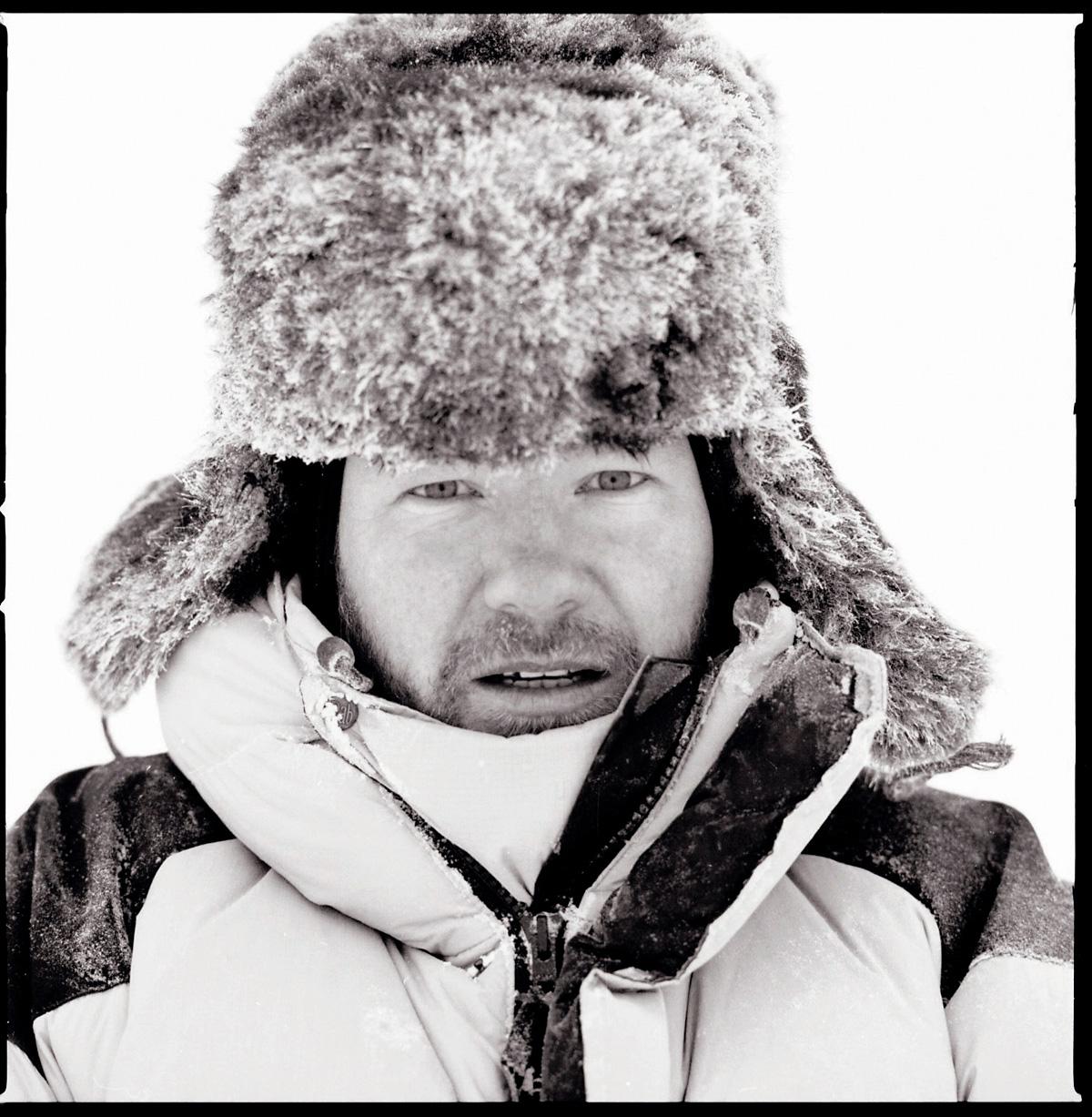

His favourite photographs are of a group of Siberian Chukchi Eskimos taken in challenging conditions in temperatures of -53C.

“We were inside the Arctic Circle, the closest you can get to the Bering Strait before it hits America. This small group of Eskimos were the ancestors of the modern indigenous peoples of the Americas 20,000 years ago. I was in full Arctic gear. Two cameras broke because it was so cold. There were only three hours of daylight at that time of year and I wasn’t sure I was going to get anything. But it was such a calm and beautiful setting, which belied the conditions.

“There was the most beautiful light, subtle blues and pinks, with the sun coming over the horizon. There were no trees or anything else around, just this incredible frozen landscape. And these Siberian Chuckchi in reindeer outfits, wearing the back leg skins as trousers, the front leg and back skins as jackets. Even the hats for the children still had the soft fur ears on them. These were really smart people, so calm, living in one of the coldest places on the planet.”

It is the most difficult jobs, he says, which are ultimately the most rewarding. He has had to make many sacrifices for his work.

“I did about 14 overseas trips last year. It’s a dream job when you are a 25-year-old single person, but not when you are married with children.” He misses garden designer wife Liberty Silver and daughters Delta Rae, nine, and six-year-old Piper.

“It’s hard work. I am up an hour before dawn trying to get the best possible light. And there’s a lot of competition out there, which keeps you on your toes.”

Digital photography has taken a bit of the magic out of it all, he says. “It was more fun when you shot a film and didn’t know what you were going to get until you got to the lab and saw what came out.”

It is an expensive career now, he says. “Styles change and equipment changes. It’s technically easier to take pictures now and photography is over-subscribed, really competitive. I would advise people not to do it for the money; you have to know what you want to say with your pictures.

“You have really got to love it,” he adds. And Read clearly does. “My work has allowed me to visit the very corners of the Earth,” he says. “It continues to satisfy my restless soul.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel