A Norman church on the Yorkshire Wolds contains a stunning surprise. In the latest of his occasional series on Yorkshire churches, STEPHEN LEWIS visits St Michael and All Angels at Garton on the Wolds.

FROM the outside, there is something pleasingly blunt about the Norman church of St Michael and All Angels at Garton on the Wolds. It stands proud on an area of high land to one side of the village, with a view southwards across rolling wolds uplands.

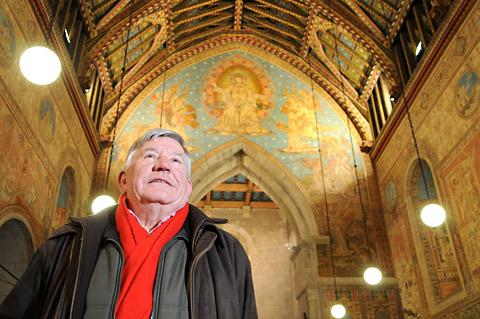

“That’s where the old village was,” says church warden Cliff Wilson, gesturing across the fields. Not far away, across those fields, an Iron Age chariot burial was uncovered in 1971 – evidence of how long people have been living and working here.

The church tower, built of honey-brown stone, is squat and powerful, with a turreted top that makes it look almost like a fortress. It would have been a Norman statement of intent, says Roy Thompson, the Diocese of York’s tourism officer: a declaration of power and authority.

It is a simple church, with to the east side of the tower a nave and chancel, but nothing more. The church was extensively restored in the 1860s and 1870s by the second Sir Tatton Sykes, of nearby Sledmere House – one of 18 churches in East Yorkshire built, rebuilt or restored by the Sykes family.

But the restorers followed the original style and architecture, even replacing an original medieval window. This faithfulness to the original design is why it looks so typically Norman from the outside today.

There are three stories to be told about the church, says Mr Thompson. One is the story of the Norman church. One is the story of its restoration by Sir Tatton. And one… He leads the way inside. You stand for a moment as your eyes adjust to the gloom. And then the only response possible is to gawp. Your neck tilts back, your eyes lift to the walls and your jaw drops.

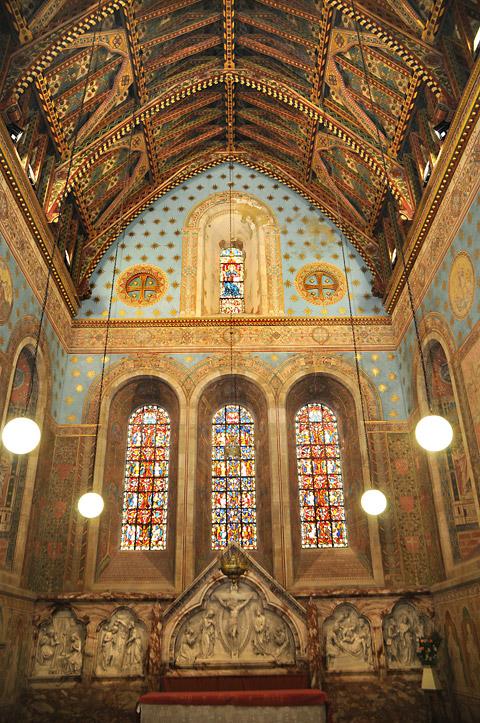

Every inch of the interior walls, it seems, is covered in paintings – delicate paintings in pastel shades that could have come straight from the brush of a pre-Raphaelite master.

They date from Victorian times, roughly the same date as the restoration of the church’s stone exterior, and they tell, in exquisite imagery, the story of the Bible.

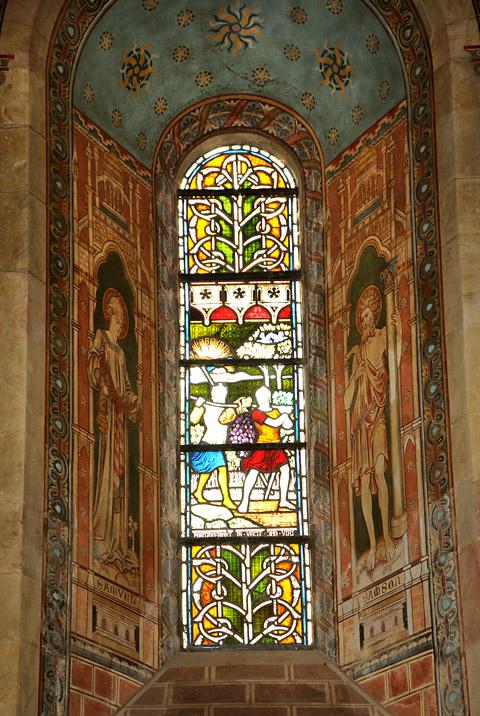

A delicate David in simple shepherd’s tunic confronts a giant, bearded Goliath. A team of labourers build an Ark out of clean, new wood, while the bearded patriarch Noah looks on. Cain raises a cudgel high above the head of his brother Abel, who reaches out an arm as if in entreaty. “Cain rose up against Abel,” says a legend beneath, to leave the viewer in no doubt as to what the painting represents.

And so it goes on. On the west wall of the nave is a representation of God the Father. Opposite, on the nave’s east wall, above the arch leading through to the chancel, is a Jesse Tree symbolising the descent of Christ from King David.

The story of the Old Testament is told in the nave. So, in a series of panels low down on the north wall, you get the story of creation and the subsequent fall of man: the spirit of God, represented by a dove, moving on the face of the waters; the creation of the sun, moon and stars; the creation of Adam and Eve; Eve tempted by the serpent; Adam and Eve after the fall, when sin has entered the world.

In the chancel, meanwhile, you get the story of the New Testament: the magi, the three shepherds, the stable in Bethlehem; Mary with the infant Jesus; the parables of the Prodigal Son and the Good Samaritan.

Each painting is rendered in exquisite detail, but the overall effect is overwhelming. The images press down on you; the colours – once your eyes grow accustomed to the gloom – almost dazzle, pale as they are. It is like walking into an opulent Roman Orthodox church in Constantinople; or one of the fine Renaissance churches in Italy. It takes your breath away. The church’s blunt exterior just doesn’t lead you to expect this.

Mr Wilson tells a story about a young man bringing his girlfriend to see the church. She came in, her head went back, and she gawped – as you must, on entering. And then she turned to her boyfriend. “And she said, ‘I’m not proposing, but what a magnificent place to get married’,” Mr Wilson says.

It is Sir Tatton Sykes we have to thank for these paintings – he paid for the work. But according to an introduction to the church written by Jill Allibone 20 odd years ago, they may have been produced at the instigation of the then vicar, the Rev Richard Wrangham.

It could be that they were an attempt to recreate a Victorian version of the kind of wall paintings that, until the Reformation, decorated the inside of almost all medieval English churches, says Roy Thompson. And they may even, according to Jill Allibone’s account, have been a reaction to the work of Charles Darwin.

His origin of the Species had been published in 1859: the Descent of Man in 1871. The paintings in St Michael’s may have been “an opportunity to ensure that worshippers in this parish were not seduced by scientific theories which flew in the face of divine revelation”, Allibone writes.

Whatever the story behind them, they are stunning.

Created in the 1870s by the firm of Clayton and Bell, the paintings were restored 25 years ago at a cost of £100,000 thanks to the support of the Pevsner Trust. And in August last year new lighting was installed at a cost of £14,000 which enables them now to be seen in their full glory.

If you do get the chance to see them, you will realise that glory is the only word appropriate.

• St Michael and All Angels Church, Garton on the Wolds. Open daily, 8.30am – 5pm.

• The church is on the Sykes Church Trail – a trail of East Yorkshire churches restored or rebuilt by the Sykes family. Dr David Neave will give a talk about Sir Tatton Sykes and the Sykes churches at 7.30pm on Friday April 26, at Sledmere House. Tickets are available, priced £12, from 01377 236637.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here