IT IS hard to imagine today the excitement thousands of onlookers must have experienced when they gathered to watch the birth of a strange new form of transport more than 180 years ago.

The date was September 27, 1825. And the event was the opening of the world’s first public steam railway licensed to carry goods and passengers.

That first railway was the Stockton and Darlington – mainly a coal line linking the pits of County Durham with Darlington.

The locomotive which made the 25-mile journey on that day was George Stephenson’s Locomotive No 1. Stephenson and his brother, James, rode on the footplate of the brightly painted engine. The world would never be the same again.

So began the railway age. The Liverpool and Manchester line opened in 1830. Others quickly followed: the Leeds and Selby in 1834, the Whitby and Pickering in 1836.

It was an age of huge excitement and rapid growth. Railway lines quickly opened across the country: linking individual towns, cities and coal-heads, then gradually being “stitched together” to form wider rail networks.

As the Victorian age gathered pace, so did the rail age. The new-fangled railways changed the face of the nation, says rail historian Professor Colin Divall, of the Institute of Railway Studies & Transport History, based in York.

By the 1850s, there was a skeleton network of railways covering much of the country.

“It wasn’t possible to go to every town and village, but you could certainly travel from one end of the country to the other by rail most of the way,” he said.

That allowed for the easy and rapid transport of freight goods, which in turn helped the development of a true national economy, says Prof Divall.

“Before the railway age, Britain was a collection of regional economies with limited trade between them. The railways led to the emerging of a national economy.”

They also revolutionised people’s ability to travel. Before, passengers had relied on horse-drawn carriages, canals, or coastal ships.

“The railways meant people could get around a lot more. It would be wrong to give the impression that they made travel for ordinary passengers easily affordable. The railways have always been expensive ways to get around. But travel wasn’t as expensive as before.”

Or as difficult, come to that.

As the rail network spread across the country, York had one man in particular to thank for the fact that it became a central hub of one of the main London to Scotland routes.

George Hudson was the fifth son of a farmer. Born in Howsham, north-east of York, he left school in 1815 and was apprenticed to a firm of drapers in York.

In 1827, under rather dubious circumstances, he received a £30,000 inheritance from a great uncle. He used it to become one of York’s most prominent citizens, becoming a councillor in 1835 and Lord Mayor in 1837.

Crucially, he also had cash with which to invest in the railways. He was determined, Prof Divall says, that York would take its place on the main London line to the north.

By 1833, he was a member of the York Rail Committee set up to develop plans for a railway line linking York with West Yorkshire to bring cheap coal to the city.

By 1837, he had become chairman of the new York & North Midland Railway Company, with George Stephenson as the railway engineer. It became part of the trunk route to London, via Derby and Birmingham, and was a huge success.

England was in the grip of railway mania, and Hudson was at the centre of things. He continued to set up rail companies and by 1848 he controlled nearly a third of Britain’s rail network, was a Conservative MP, and had earned the nickname the Railway King.

His fall was as spectacular as his rise. He was accused of sharp business practices, his shares fell in price, and he ended up first in a debtors prison and then in France, exiled and virtually penniless.

But his railway legacy survived.

Hudson’s great York rival, George Leeman, promoted the merger of a number of railway lines into the North Eastern Railway in 1854, effectively picking up many of the pieces after Hudson’s fall.

The NER ran from Doncaster through York and northwards to Berwick-upon-Tweed.

It was the first of the really large, monopolistic rail companies: and with the Great Northern Railway, which operated between London, Doncaster and York, provided the basis for much of what was to become the East Coast Main Line.

By 1860, GNR, NER and North British Railways in Scotland were running a common pool of passenger vehicles on what had become a London-Scotland east coast route between King’s Cross and Edinburgh. By the 1870s, the main trains on this route were already known as the Flying Scotsman.

The rail age had well and truly arrived, and York’s place at the hub of one of the key routes was secure.

Hudson vs Leeman

YORK’S two great railway figures, George Hudson and George Leeman, were polar opposites, as well as being hated rivals, says journalist and historian Robert Beaumont.

Mr Beaumont, author of a book about Hudson, says he was a man of enormous energy, commitment and vision. “He was a big boozer, very flamboyant.” Leeman, meanwhile, was abstemious and cold.

He was also, Mr Beaumont maintains, a hypocrite, doing all he could to oppose Hudson, before effectively taking over from him. “He was a snake in the grass.”

Nevertheless, he did play his part in ensuring York’s place on the railway map, Mr Beaumont agrees.

The city owes a great debt to both men.

The great age of steam

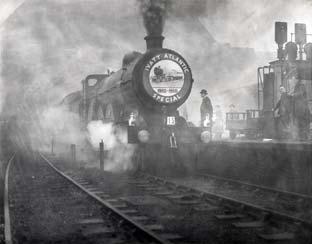

WHAT many would regard as the great age of steam began in the 1920s. In the aftermath of the First World War, the myriad rail companies operating across Britain were rationalised into just four. The two great rivals operating routes from London to the north were now the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) operating routes up the east coast, and the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMSR) operating routes up the west coast.

The LNER’s flagship locomotive during the 1920s was the A1 Pacific class designed by Sir Nigel Gresley, the most famous of which is The Flying Scotsman, now being restored by the National Railway Museum.

But while there was fierce rivalry between the east and west coast companies, there was an agreement not to compete on speed – the legacy of a series of accidents in the 1890s, says Prof Colin Divall.

All that changed in the 1930s. Sir Nigel Gresley developed a new, streamlined locomotive, the A4 Pacific. The most famous of these was to be Mallard, which in 1938 set a new speed record of 126mph.

But well before then, other A4 Pacifics of the LNER’s Silver Jubilee service were reaching speeds of well over 100mph, and slashing time off the London to Edinburgh run.

LMSR’s response was the Sir William Stanier-designed Princess Coronation class locomotive, typified by the Duchess of Hamilton, now at the NRM. It wasn’t as fast as the A4 Pacific, but with its Art Deco styling it was equally sleek and beautiful, and the height of luxury.

The Second World War put an end to the competition between the east and west coast rivals. The Government took over the railways, and after the war they were nationalised to form British Railways in 1948.

The age of steam came to an end at the beginning of the 1960s with the launch of new diesel Deltics, then came the High Speed Trains of the 1970s and 1980s, electrification of the East Coast Main Line in the late 1980s, and then privatisation in the 1990s.

But the franchise has proved expensive to maintain, with both GNER and now National Express East Coast pulling out.

The future remains uncertain.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here