English folk music’s guiding light will finally receive a lifetime achievement award next month. MATT CLARK met up with him at his North Yorkshire home.

IT’S one of those slate grey days in Robin Hoods Bay; a day when everything appears to be monochrome, even the crimson pantile roofs.

Then along comes Martin Carthy to brighten the murk with a jaunty scarf, just like he’s brightened the lives of countless music fans for more than half a century.

When he was a schoolboy during the early Fifties, the music was as drab as the lashing North Sea in winter. Pop songs were no more challenging than How Much Is That Doggie In The Window or You’re A Pink Toothbrush, I’m A Blue Toothbrush.

And then Lonnie Donegan stormed on the scene in 1955 with Rock Island Line.

It changed everything overnight. Skiffle groups sprang up everywhere and guitars began to sell like hot cakes.

The musicians who emerged from that scene read like a who’s who of British pop, from Cliff Richard and Jimmy Page to John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

Carthy was one of those budding guitarists, but he followed a different path and went on to set the benchmark for the revival of English traditional music.

Even today he remains the movement’s pivotal figure.

“When the skiffle boom burst I got bitten by the folk bug because intuitively I like the idea of a song having a history,” says Carthy. “I’ve always liked proper songs.”

In 1958, he heard his first proper song, courtesy of Sam Larner, an 80-year-old Yarmouth fisherman. For Carthy this was a life-changing moment.

“I was thunderstruck. It wasn’t pretty, but the songs were delivered with such dash and passion that I walked away reeling. Well that was it.”

At first Carthy played fairly safe. Then he threw away his chord book, retuned his guitar to an open tuning and proceeded to wallop his bass strings with a heavy thumb pick. It was a revelation.

From then on, everyone wanted to sound like Martin Carthy.

They still do.

One reason is the particular chime he achieves thanks to the deep, resonant tunings. At first be began with Davy Graham’s DADGAD; then, after a number of midnight-oil experiments, he discovered CGCDGA, which suited his voice better.

“I remember thinking ‘cor, aren’t you clever’. Then someone mentioned the cello, which is tuned CGDA. I thought you sod, you got there 400 years ago.”

Carthy believes tradition is a process, not an edifice; one with great stories to tell and even greater lessons to learn.

Perhaps the best way to annoy him would be to suggest he is some kind of museum curator – and a few have.

Nothing could be further from the truth. For Carthy a song on a page is nothing. It is either played or it perishes.

That said, until the 1960s revival, much of the collected traditional music was doing just that, perishing under lock and key in London.

“It was incredibly frustrating,” says Carthy. “Cecil Sharp House kept an extraordinary grip on what could be released and there was this feeling at the time that, ‘We are the guardians of English tradition and we are guarding it from you’.”

Fortunately, Carthy managed to befriend a librarian there by the splendid name of Mrs Noise and so began a lifelong fascination with folk music.

He has also been responsible for unearthing many songs once thought lost and painstakingly completing others that existed as fragments in the notebooks of collectors such as Percy Grainger.

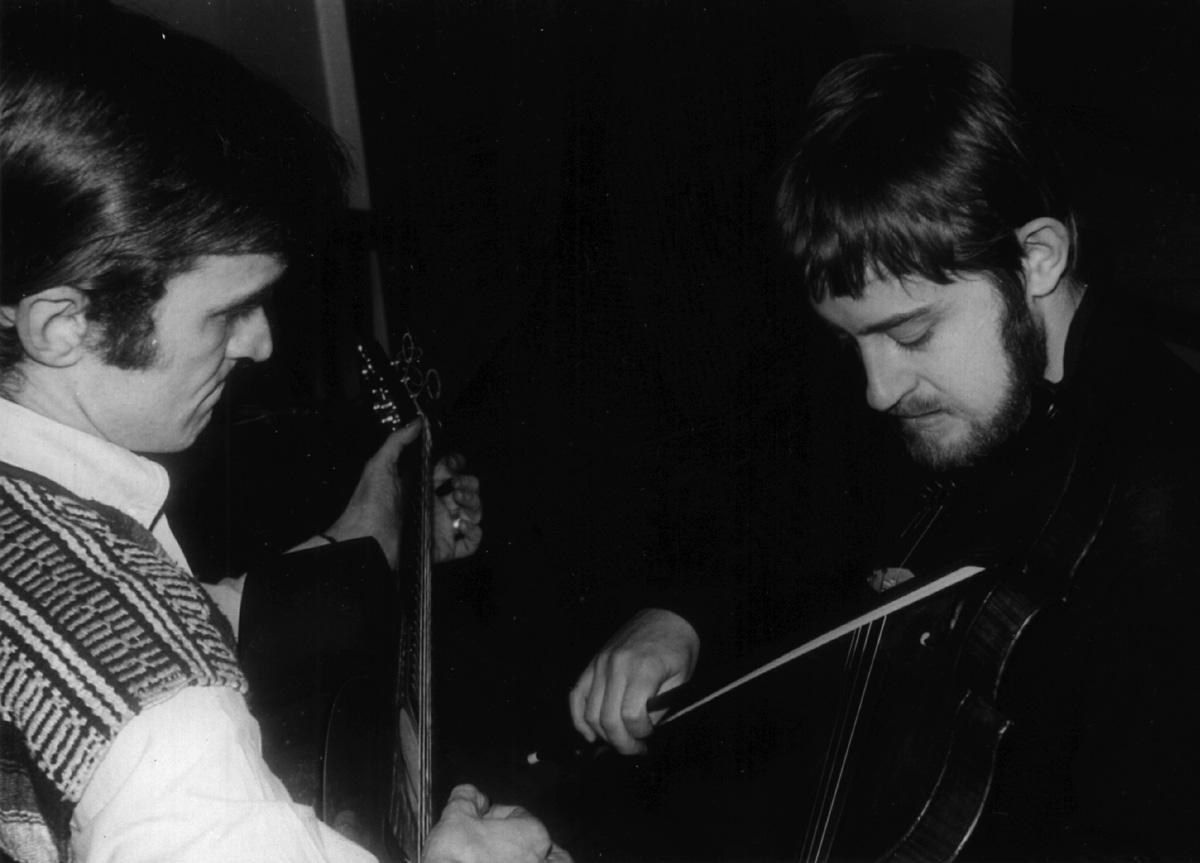

Such dedication set Carthy apart and while fame and fortune beckoned Bob Dylan and many other Sixties singers, he remained true to his club roots as one half of a legendary duo with Dave Swarbrick and as one fifth of folk’s royal family, The Watersons.

But arguably he is at his most mesmerising as a solo artist.

“I love taking risks on stage, especially with a song I’ve been doing for ages. The first time it happened, I started playing the accompaniment in a totally upside down way and began to think, ‘This is interesting – what are you doing?’ Then I thought sod it, let’s keep going and see what happens. It was very exciting.”

Never one to play safe, Carthy even performs songs he has never rehearsed, believing the first time is often the best he will sing it because his focus is “absolutely tight”.

Indeed on most of his albums there is at least one song he had never sung before entering the recording studio.

“But I didn’t sing the particular song [of Sam Larner’s] that blew me out of my socks until I really began to get used to traditional music. Just because I’m English doesn’t mean I’m going to understand English songs. Sometimes they are ever so straight, but when they are unorthodox, by God they really are.”

Traditional singers regularly leapt off at a tangent, but rarely from singing off kilter.

Despite being unschooled musicians, they had rules. “It’s about understanding the way the whole thing works. Doing your own version is exactly what you don’t do. That would be to miss the point. When you hear something you want to sing, it is incumbent to pass on the moment you said, ‘Wow I want that, how do I get there’.”

As folk songs come from different ages, with different values, some can sound unpalatable to modern ears. Carthy prefers instead to select songs that deal with issues in a more reflective way.

“Basically what you get from the much older songs, the big ballads, is a huge morality play. They are teaching songs and say ‘That won’t do’. The reaction you get from an audience is ‘Yes, you’re right, it really won’t do’.”

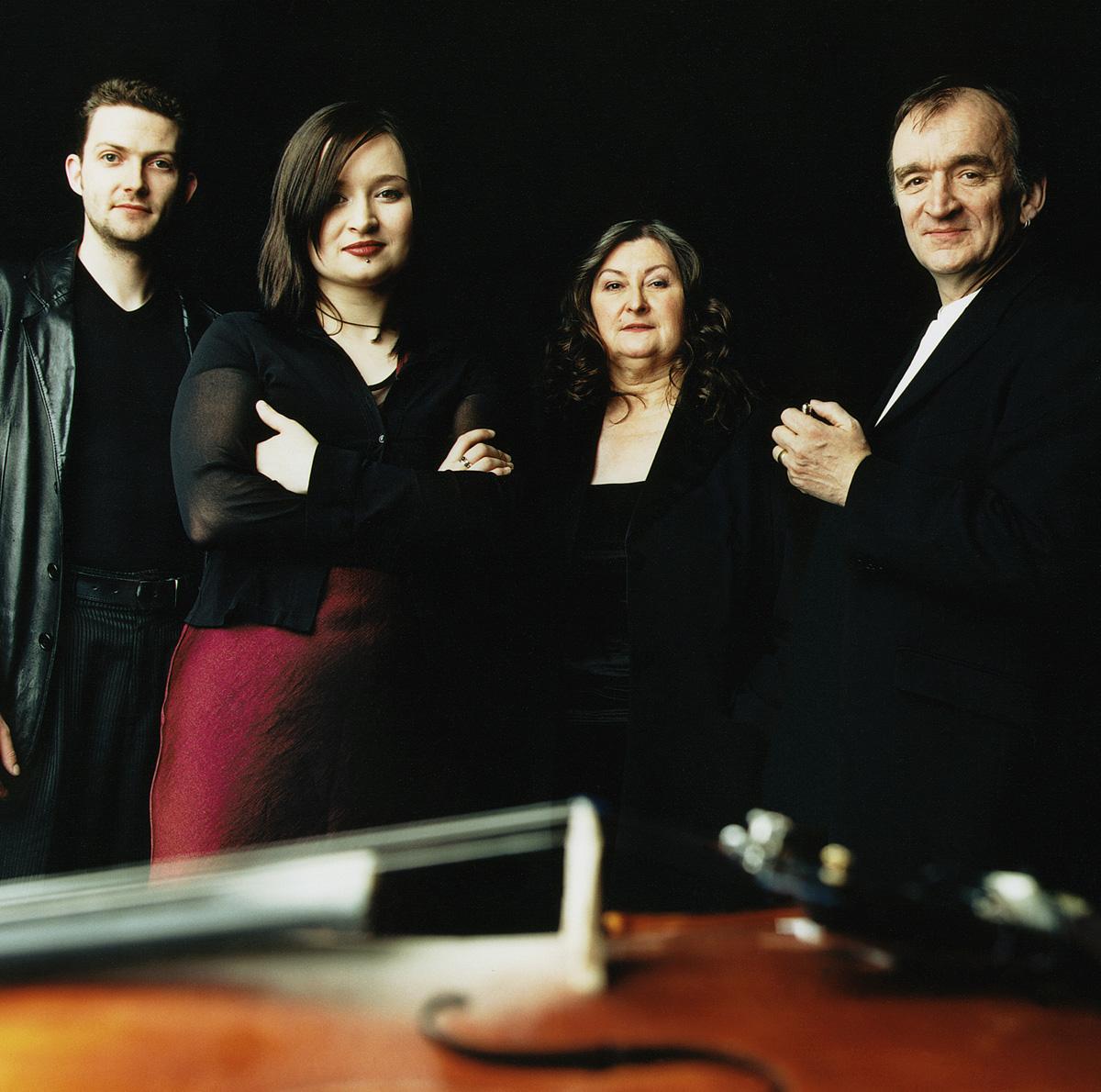

Carthy released his eponymous debut album just short of half a century ago and it’s been ten years since his last solo effort. But finally there is good news. In January he finished recording his first ever album with daughter Eliza.

“I don’t make many records because I think of myself as a live performer. I trust live performance much more than recording, but making this album with Eliza has been really exciting. We’ve come up with some really good stuff.”

Also long overdue is a lifetime achievement award, but that will be put right next month at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards.

“I’ve had this huge adventure for 50 years and I’m getting an award for it.

Well thanks very much, but I’ve had a fantastic time and it’s been, massively educational. It should be me handing out the award.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel