NATALYA WILSON finds herself immersed in a new book about the region’s lifeboat stations.

HUNDREDS of lives would have been lost over many decades had it not been for the work of the crews of lifeboat stations up and down the country’s coastlines.

In the North East and Yorkshire alone – from Sunderland down to the Humber – there are 14 lifeboat stations, some in large ports, others in small villages, and many of those are situated along the coastline in our area.

In his latest book, Lifeboat Stations of North East England from Sunderland to the Humber Through Time (Amberley Publishing, £14.99), North Yorkshire-based historian Paul Chrystal looks at past and present pictures of these stations and the people who worked in them, paying tribute to the brave men and women over the decades who have risked their lives – and in some cases, paid the ultimate price – to aid those in peril on the seas.

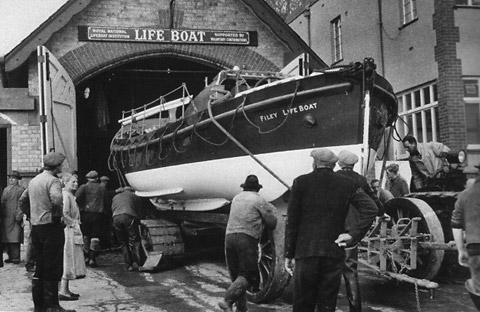

Beautifully illustrated with 200 images – some of which date back more than 100 years – the book shows the changing faces of the lifeboat stations at Sunderland, Seaham, Hartlepool, Redcar, Staithes, Runswick Bay, Whitby, Robin Hood’s Bay, Filey, Bridlington, Withernsea and Spurn Point.

These images are supported by informative facts about these lifeboat stations, the people who worked in them, the boats launched and tales about some incredible rescues that have taken place, which are bound to interest any reader who enjoys taking a fascinating, enjoyable and nostalgic journey through times past.

Paul tells of the many lifeboats that have been launched at these stations, including one of the hardest launches in history.

In January 1881, the brig Visitor foundered off Robin Hood’s Bay during a blizzard. The crew took to their boat but were forced to remain outside the harbour.

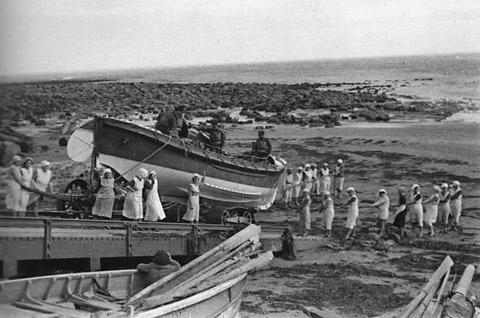

It was impossible to launch the Whitby lifeboat at Whitby, so 18 horses and about 200 men from Whitby and Robin Hood’s Bay hauled the Whitby lifeboat, the Robert Whitworth, six miles from Whitby to the bay, in snow drifts seven feet deep in places.

At the end of the two-hour trek, the men lowered the lifeboat down the steep street towards the sea with ropes. The first launch had to be aborted – the oars were smashed by a wave.

At this point John Skelton, a local man with knowledge of the bay, waded in and swam towards the Visitor’s crew, plotting a safe route for the lifeboat, now with 18 crew on board, to follow.

Spurn’s lifeboat men are pictured wearing the cork lifejackets, or lifepreservers as they were then known, issued by Hull from 1841, but it is not just men who were involved in working on the lifeboats.

The women of Runswick Bay launched the Robert Patton – The Always Ready in March 1940 to assist the Buizerd of Groningen. The six crew were saved.

However, this was not the first time women had helped. On April 12, 1901, most of the able-bodied men of the village were at sea in their cobles when the lifeboat, Jonathan Stott, was needed to offer assistance. Only boys and old men remained inshore at the time so the ladies decided that the men and boys would man the vessel and they would launch it. All the cobles returned to shore safely.

Lifeboat rescues are also evident inland, too. In September 1931, the William Riley was hauled one and a half miles inland from Whitby to Ruswarp when the village was flooded due to heavy rains, with water rising to more than eight feet deep in places.

On arrival, the boat was launched into the flood and saved five villagers from their cottages, including a 90-year-old bedridden lady.

The life of the men of Filey who worked on the sea even prompted some literary prose from one very famous visitor to the town.

Charles Dickens visited Filey in 1851, recording his observations in his Household Words: “The seaside churchyard is a strange witness of the perilous life of the mariner and the fisherman… Filey, a mere village, well-known to thousands of summer tourists for the noble extent of its sands and the stern magnificence of its so-called bridge, or promontory of savage rocks, running far out into the sea, on which you may walk at low water; but which, with the advancing tide, becomes savagely grand, from the fury with which the ocean breaks over it.

“In tempestuous weather this bridge is truly a bridge of sighs to mariners, and many a noble ship has been dashed to pieces upon it.

“One of the first headstones which catches your eye in the little quiet churchyard of Filey bears witness to the terrors of the bridge: ‘In memory of Richard Richardson, who was unfortunately drowned December 27, 1799, aged forty-eight years…’”

There are many other fascinating tales but if the temptation of this nice tome isn’t quite enough to make you reach for your purse, the fact that all proceeds from the book are donated to the RNLI should tip the balance.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article