TWO hundred years ago, in the spring of 1812, Britain was at war with Napoleon. George III was King, Charles Dickens had just been born and the Luddites – a social movement protesting against ‘new’ technology, such as automated looms, which were putting manual labourers out of work – were rampaging across wool and cotton mills in the north of England.

And in York, a group of well-intentioned people with church connections had an idea: to set up a school for poor children.

The York Diocesan Board of the National Society for the Education of the Poor was formed on March 13, 1812. Its mission: to set up a school in York for the children of the ‘labouring classes’, one that was designed to turn them into “useful and respected members of society”.

The school opened on May 21, 1812. It had just one master – 24-year-old Samuel Danby, who had been appointed on a salary of £30 a year – and 200 pupils. Much of the teaching was to be done by older boys known as monitors, who also helped out with discipline.

“It was an attractive method in the 19th century as large numbers of pupils could be educated cheaply using one master and a number of monitors,” notes a splendid new book, Manor Church of England School 1812-2012, produced to mark the school’s bicentenary.

It wouldn’t have been known as the Manor School in those early days, it was more likely just The York National School. The name ‘Manor’ was probably adopted when, in 1813, the school moved into King’s Manor. It was to remain there for the next 110 years.

There is a wonderful history of the school which opens the book, one which draws extensively on the school log book to bring to life long ago schooldays.

“Kept a lot of the lads in to get them up for their standard examination next month,” notes an entry for September 1867. “Boys dislike it immensely.” We bet they did.

The log also reveals that the quality of some of the pupil teachers left a lot to be desired.

“Had to speak to Potter for allowing the boys in his class to leave school in a disorderly fashion,” notes an entry for May 1863. In June 1863, there was another: “Potter absent from his lesson on Friday evening with no better excuse than ‘he could not come because it rained so fast’.”

Then, in January 1864, there was a brief, terse note: “Potter’s apprenticeship expired.” We do not, sadly, find out what happened to the young man subsequently.

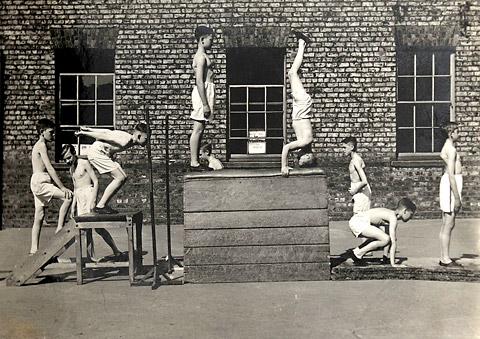

The book is packed with photographs of the school in its early days – at the Kings Manor, and following its subsequent moves to Marygate in 1922 and, after the Baedeker Raid of April 1942 in which the school was badly damaged, to Priory Street.

Mr DH Cooper, the head at the time, wrote in his log of the bombing: “When I arrived at the school at 5am, I found the building in ruins, the western wing having been directly hit by a bomb.

“The boys were dismissed until further notice… I suggested an approach should be made to the managers of the Priory Street Higher Grade School for accommodation in their building.”

The history chapter of the book, illustrated with old photographs and even copies of log entries and school records, is fascinating. What really brings the book to life, however, is the more recent memories.

In January, the school put out an appeal for stories and photographs. It was inundated by people who came forward with recollections of their schooldays. Alf Sanderson, now 81, recalled his days at the school from 1942-1944.

The head teacher, the aforementioned Mr Cooper, was very strict, he says. “We lads used to play football at lunchtime and we were supposed to stop the game when the head blew his whistle. Once, we just ignored it and carried on playing. Mr Cooper gave each of us, that’s 40 lads, remember, two strokes of the cane on the backside – for disobedience.”

Gill Cossham, nee Sambrook, was at the school from 1965 to 1970, and remembers the move from Priory Street to the new school in Boroughbridge Road.

“There had been floods in York and a dry cleaner’s near the Priory Street School had been constantly cleaning flood-damaged carpets,” she recalls.

“The smell was awful. When we moved to the new building, Cravens was nearby with some lovely smells of sweets wafting through the air – much better!”

More recently, former school caretaker Richard van den Heever remembers teacher John Deadman’s science lab experiments.

Mr Deadman was the epitome of the ‘mad professor’, Mr van den Heever recalls. “His science lab was in need of a tidy, so I suggested… that I would replace all the damaged ceiling tiles… “His reply was an unequivocal ‘Don’t even think about it… I intend putting holes in the rest of them before I leave in 12 months time’.”

The mystery was soon resolved. “It all had to do with his experiments during lessons when he made a rocket from an empty coke bottle,” Mr van der Heever writes This really is a wonderful book – 100 generous A4-size pages packed with class and sports photographs from down the ages, and with countless memories from pupils and staff past and present.

For anyone, of whatever age, who was lucky enough to go to Manor, it will be a real treat.

• Manor Church of England School 1812-2012 is available from the school, priced £10, or from Waterstone’s or the Acomb, Poppleton and city centre libraries, priced £12.

York then and now

1812

Size of Manor School: one master, 200 boys. Older boys help with teaching.

Population of York: 27,486.

Average income: £1 a day.

Life expectancy: 37 years, although it was a major achievement for women to survive childbirth.

House prices: few owned houses. Even the gentry leased.

Journey time from York to London: 20 hours by coach and horses.

2012

Size of Manor School: 93 staff, 907 students.

Population of York: 198,800.

Average income: £22,500 per year.

Life expectancy: women 81.5 years, men 77.4 years.

House prices: average house price in York £209,765: 68 per cent own their own homes.

Journey time from York to London: one hour and 49 minutes by train.

Source: Manor Church of England School 1812-2012

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here