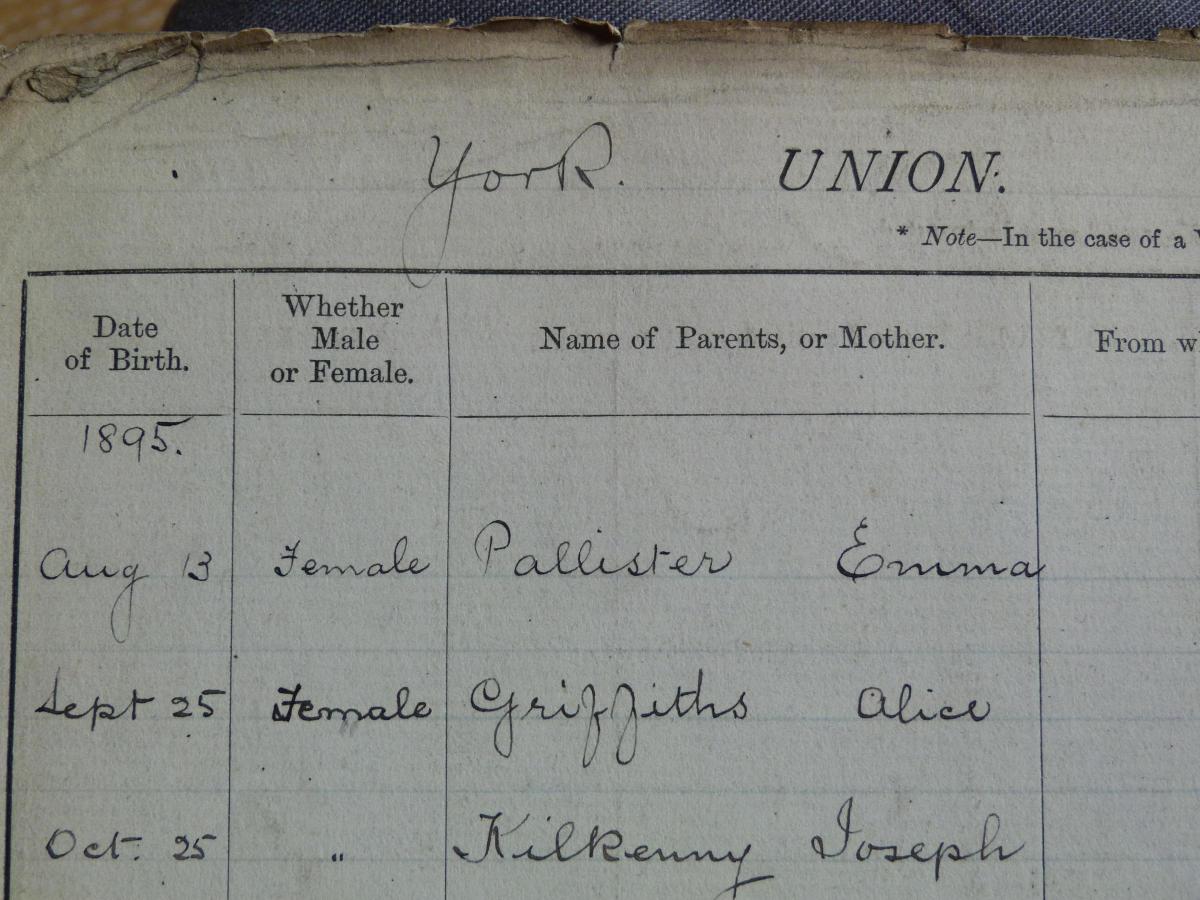

Emma Pallister, is the name of the young woman scratched in a spiky clerk’s handwriting in the ledger of the York Union Workhouse for August 13, 1895.

She lived in the parish of St Giles, York – so Gillygate, more or less – and she’d entered the workhouse on Huntington Road to give birth to a baby daughter, Elsie.

Elsie is recorded as being baptised ‘in house’ (ie in the workhouse). And there the entry ends.

The next entry in the ledger is dated just over a month later. This time, the young mother is named as Alice Griffiths, from St Wilfrid’s parish. But no name is given for her baby. Instead, in the column headed ‘remarks’, there is a single word: “Stillborn”.

That same word appears twice more on the same page of the register: a litany of tragedy inscribed in neat ink in the pages of a book written 120 years ago.

We don’t know what happened to poor Alice Griffiths, the destitute young woman who came to a place of last resort to give birth, only to lose her baby.

But we do know what happened to Emma Pallister and her daughter Elsie. Because 122 years later, Elsie’s granddaughter is York’s first citizen, the Lord Mayor Cllr Barbara Boyce.

Looking at that entry in the workhouse ledger is obviously an emotional experience for Cllr Boyce. At one point, as archivist Julie-Ann Vickers leads her through the story of her grandmother and great-grandmother, she’s close to tears.

It quickly becomes clear that the journey from workhouse to first citizen in just two generations was not an easy one.

Explore York archivist Julie-Ann had been researching the Lord Mayor’s family through census, poor law and workhouse records for a ‘Who do you think you are?’- style account of Cllr Boyce’s ancestry.

Lord Mayor Barbara Boyce, left, and archivist Julie-Ann Vickers study the workhouse records

Emma, she discovered, had been born in Cockerton near Darlington in 1873 to Matthew Pallister, a gardener, and his wife Pamela Eden.

Pamela died not long after, leaving Emma motherless. Matthew married again, this time to a woman named Mary Agar. And by the time of the 1881 census eight-year-old Emma, her father Matthew, her step-mother Mary and her half-brother Matthew, who was just two months old, were all living in York, at 10 Groves Yard off Watson Street in Holgate.

The census records several families living at the same address. “A lot of these buildings were tenements clustered around a yard where the shared toilet was,” explains Julie-Ann.

Matthew, Emma’s little half-brother, seems to have died when he was just a few months old. By the 1891 census Emma, then 18, was working as a domestic servant at 1 St John’s Crescent off Lord Mayor’s Walk. And it was about then that her life appears to have gone off the rails.

By 1893 the Pallisters had moved to March Street in The Groves. And it was there, when she was about 20 and still unmarried, that Emma gave birth to a baby son, Fred.

Having an unmarried mother in the family was clearly a source of some shame. Fred may have been passed off as his grandfather Matthew's son. "For a long time I thought that he was her (Emmas's) younger brother!" Cllr Boyce says.

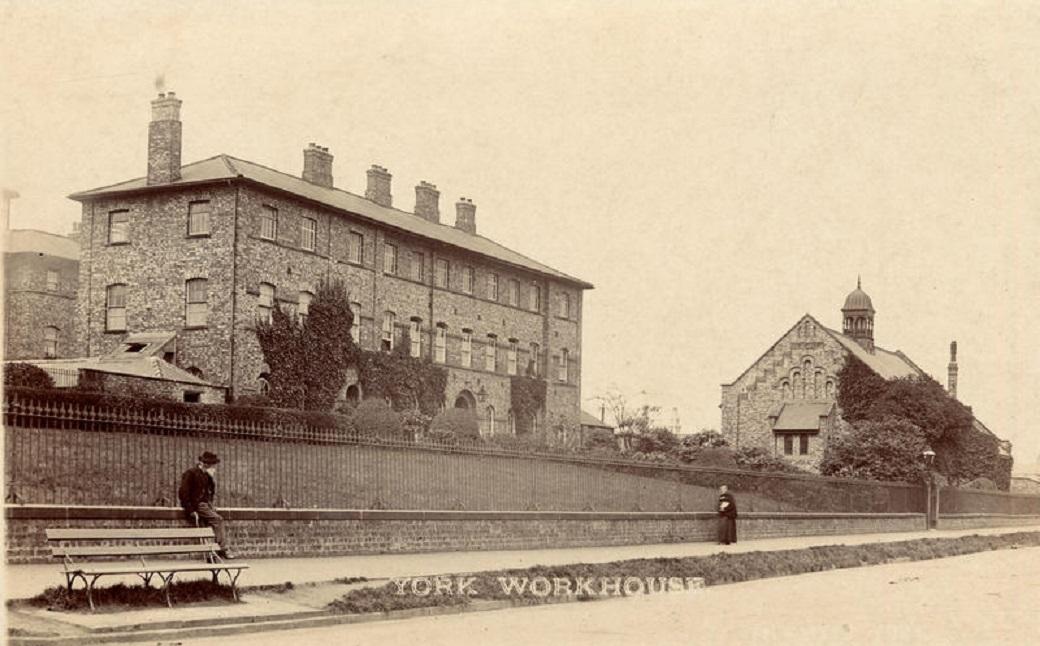

Two years later, in 1895 and still unmarried, Emma entered the workhouse to give birth again, this time to Elsie, Cllr Boyce's grandmother.

We don't know why she had to go into the workhouse to have Elsie, rather than giving birth at March Street, where her son Fred had been born: although the stigma of being an unmarried mother may have had something to do with it. "She may not have been getting support from the family," says Julie-Ann.

Emma and Elsie were discharged from the workhouse on November 1 - but were back again by November 6. "It may have been that she tried, but just wasn't able to stand on her own two feet," say Julie-Ann. Cllr Boyce is in thoughtful mood, contemplating those events of more than 120 years ago. "I always used to say to myself that she must have tried to make a life for her daughter," she says.

She may have tried, but it seems she didn't succeed. Within a year, she had given Elsie up for adoption. By the time of the 1901 census, Elsie was living with the Martin family in Newbiggin Street, The Groves; her brother Fred was still living with his grandfather Matthew Pallister at March Street - and Emma was working as a domestic servant in Harrogate.

Lord Mayor Barbara Boyce with the ledger in which her grandmother's birth is inscribed

Fred grew up with his grandfather and step-grandmother and by the 1911 census was still living with them, and working as a chocolate moulder at Rowntrees. Elsie, meanwhile, grew up with the Martins. By the 1911 census, they had moved to Union Terrace and Elsie, now aged 15, was working as a 'chocolate creme packer'.

And her mother?

Emma seems to have continued to lead a chaotic life. At some point, when she learned that her daughter had found work, she seems to have tried to make contact again, possibly in the hopes of getting some money.

Then, by the time of the 1911 census, she turns up in the workhouse again - this time in Selby, and this time with yet another child, a little boy called John. Then she disappears from the record, apart from an Emma Pallister who appears on the electoral role in Selby in the 1920s.

She appears to have been very much the 'black sheep' of the family, Cllr Boyce admits.

"I know that in the family she wasn't considered to be very nice." But she clearly had a very hard life. And she may well have had a difficult childhood herself, says Julie-Ann - after all, her own mother died when she was very young, and she was brought up by a step-mother.

For Cllr Boyce, her great-grandmother's life illustrates just how tough life could be for working class women in Victorian times, when they were dependant on men and had little or no safety net if things went wrong.

"Her story tells you so much about what awful lives some working class women had 100 years ago," she says.

"I'm only two generations from the workhouse, but how opportunities have changed.

"There's still a long way to go, and still people who are struggling. But not like Emma. Just one or two generations ago there were people who were absolutely destitute, and in the workhouse with no options."

THE RECORDS

York's poor law and workhouse records have been closed to the public for more than a year while they underwent cataloguing and conservation.

They re-opened last week, and can now be visited by members of the public keen to find out about their own ancestors.

Lord Mayor Cllr Barbara Boyce believes there may well be many families in the city today whose ancestors either spent time in the workhouse, or who applied to the York Poor Law Union for relief.

She's keen to encourage those with an interest in their family history to visit the records.

"If nothing else, it helps you to realise what cooperatively privileged lives we have today," she says.

Archivist Julie-Ann Vickers says there are countless stories contained in the records, which shed real light on life in Victorian York.

They include:

- Richard Chicken, born the son of a relatively well-off wine merchant in Low Ousegate in 1799, who worked variously as a clerk, an actor, a schoolmaster and a poet, and yet still managed to fall on hard times. With a wife and 11 children to support, he regularly had to apply to the York Poor Law Union for relief payments - often to pay for the burial of his children, many of whom fell ill with scarlet fever and didn't survive to adulthood. At one point Mr Chicken worked as a clerk in the same railway office in York where Charles Dickens' brother Alfred worked - and it is thought he may have been the inspiration for Dickens' character Mr Micawber.

- Cecil Frederick Moon. Moon was the 'gentlemanly'-looking son of an MP (gentlemanly apart from the fact that he had a tattoo of a vampire on his left arm) who, in 1907, absconded from York with a young actress named Violet Campbell - leaving behind his wife, Frances, their 13-month-old son, and a baby. Without Cecil's wages, the family was destitute, and Frances had to apply to the York Poor Law Union for relief. They were granted 3s 6d a week and some milk for the children. A warantn complete with full description was issued for Cecil's arrest by York chief constable James Burrow - and within two weeks Cecil had been arrested. He was sentenced to one month's hard labour at HM Prison Wakefield.

- The York Poor Law Union and workhouse records can be accessed through the reading room at Explore York central library.

The reading room is open on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Saturday. You are advised to make an appointment first: email archives@exploreyork.org.uk or call 01904 552800.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel